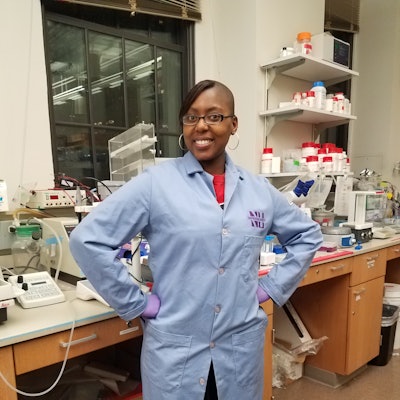

Schnaude Dorizan, doctoral candidate in neuroscience at Northwestern University

Schnaude Dorizan, doctoral candidate in neuroscience at Northwestern University

“I had this worry that our green cards could be revoked any minute, so I couldn’t be bad," she said of her childhood. "I gave myself this responsibility of protecting our immigration status by not misbehaving.”

Her family lived in a neighborhood where shootings were almost routine, so she wasn't allowed to leave the house much. But sitting at home, Dorizan loved to read, especially mystery books. And when she wasn’t reading, she was intently watching people.

“I’ve always been an observer in my environment,” said Dorizan. “I sat back and tried to make sense of a person’s behavior. I know this person is a good person, but why did they do this bad thing? I guess those were the beginnings of me becoming a scientist, seeing people interact and taking notes on patterns.”

That scientist impulse brought Dorizan to the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) for her undergraduate degree in psychology and biology. She was part of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program, which supports underrepresented students in STEM fields.

“The program laid the foundation for where I am today, but it was a bit lonely,” said Dorizan. “I seemed to be the only one with my background from an underfunded school in New York City without the opportunities that a lot of my cohort had. The other students knew what a PhD was, but I didn’t. I couldn’t really articulate my feelings of not-belonging at the time.”

Those feelings, however, later inspired her to advocate for students from underrepresented communities also trying to thrive in academia. Dorizan, 29, and now a doctoral candidate in neuroscience at Northwestern University, recently received Northwestern’s McBride Award. The honor, named after the former dean of The Graduate School, annually recognizes a graduate student who demonstrates an outstanding commitment to diversity and inclusion.

"When I think of Schnaude, I think of her as a change agent, a champion, and a collaborator of social justice, diversity, and belonging," said Damon L. Williams, associate dean for Diversity and Inclusion at Northwestern's Graduate School. "She has been fantastic in pushing for, cultivating, and championing diversity. She wants the voiceless to be heard."

In 2012 while an undergraduate, Dorizan joined a summer program at Northwestern. She saw first-hand the institution’s dedication to inclusion. When she graduated from UMBC a year later, Dorizan knew where she wanted to study neuroscience for her doctorate.

“I chose Northwestern because I saw how they went above and beyond for an undergraduate like me,” she added.

Her dissertation examines a surprising subject: rat whiskers.

“A lot of people are very confused when I say that I study rat whiskers,” said Dorizan. “They’ll ask, what utility would that have to humans? But studying rat whiskers is important because rats use their whiskers the same way we use our hands.”

Schnaude Dorizan, doctoral candidate in neuroscience at Northwestern University

Schnaude Dorizan, doctoral candidate in neuroscience at Northwestern University

Outside of the lab, Dorizan’s first few years at Northwestern were welcoming thanks to the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, which was created at the time by Dr. Dwight McBride, who is now the president of The New School.

But a change in leadership brought a shift in resources. The Office soon became short staffed, pulling back on the positive impact it once had on students, according to Dorizan. That pushed her to be more active on campus.

“A lot of events and services for students had stopped, so I wanted to be part of getting those opportunities back,” said Dorizan. “ I wanted to help students like me feel like they belong.”

She interned at the Office and twice became president of the Black Graduate Student Association. Dorizan also founded and became president of the Graduate Women of Color Association.

"Schnaude goes a step beyond the call of duty, even when she is at the finish line of her program," said Williams. "Whether she's recruiting at a booth during a conference for eight hours a day or taking a student in need of support out for lunch or stepping in at the last minute to serve on a panel about inclusion, Schnaude is eager to make this the most social and just environment for all students."

In February 2020, Dorizan and fellow graduate student leaders went a step further. They issued a letter to the University on ways the campus could better support underrepresented students.

“One demand was increasing the capacity of the counseling and psychological services on campus. They are really understaffed,” she said. “There just aren't enough therapists, so we asked for more counselors, especially counselors of color and counselors privy to LGBTQ+ issues.”

Dorizan noted that the graduate student leaders had been building momentum. Yet when the pandemic hit, that all slowed down, though COVID-19 shed light on the equity problems that their letter pointed out.

“With the mental health issue, for example, people really needed those counseling services in the pandemic,” said Dorizan. “We were figuring out how to exist in isolation and get through all this stress. But you couldn’t make an appointment. If you wanted to talk to somebody, you had to wait a month. If you’re in a crisis, that’s too long to get help.”

To graduate in a few months, Dorizan has lately been more focused on her research and less active on campus. She expects to complete her doctorate in December 2021 or March 2022. The pandemic had delayed her degree due to limited lab access. Yet Dorizan has been impressed with the progress that student advocates have made so far.

“My attention has for far too long been divided between my work and my advocacy,” she said. “But I will say that, however slowly, the institution is getting to the demands. Now, for example, the Office of Diversity and Inclusion has more power to hire more staff members. It did take awhile, but we were heard. We stayed on their necks until we were.”

Williams added that diversity among doctoral students increased by 50% since he started his position at Northwestern in 2017. He credits that boost in part to Dorizan's leadership.

"She will do whatever is necessary to be at the table and on the frontlines," he said.

Dr. Daniel Dombeck, associate professor in neurobiology at Northwestern and chair of Dorizan's dissertation committee, agreed with Williams on the impact that she has had on campus.

"Schnaude has been an incredible force championing inclusion and acting as a strong advocate for diversity, service, and student engagement in our Northwestern community," said Dombeck, who noted that she is also a representative of the NUIN Graduate Student Advisory Committee and a member of the Northwestern University Brain Awareness Outreach Group. "I think these efforts by Schnaude have made our community better and are worthy of all our praise."

As her program comes to a close, Dorizan pointed out one of the biggest challenges underrepresented students still face in the pandemic.

“Northwestern, for all of its flaws, is a fantastic university," she said. "I have gotten all kinds of training. So, it’s not to say resources aren’t available to students. But you need to know who to talk to. And I think students are more cautious lately with asking for what they need.”

To Dorizan, building a community of graduate students, professors, and administrators that lift her up has been critical to her journey, to helping her feel like she belongs.

“It’s people like the chair of my dissertation committee, who will always send me messages saying you can do this, you got this, you’re a brilliant scientist, they have made the difference for me,” said Dorizan. “Having the support of people like that is really what has carried me this far.”

As for her next steps after graduate school, Dorizan is open to working in industry. Yet she is also considering higher education administration to support underrepresented students.

“I don’t want to stay in academia. I feel like I’ve done enough to try to reform this space, but this space is not one that I would thrive in as a faculty member," she said. "But I want my hands still in science. And maybe to help students be the best that they can be.”

Rebecca Kelliher can be reached at [email protected]