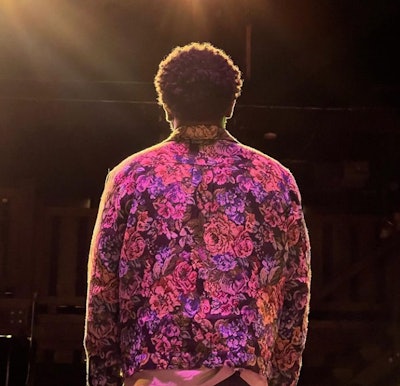

Durmerrick Ross stands beneath lights at an event.

Durmerrick Ross stands beneath lights at an event.

Getting into Howard University was a dream come true for Durmerrick Ross. It was fall 2016 and the nation was alive with activism in the wake of Donald J. Trump’s election and upcoming inauguration.

Ross jumped into life at Howard with aplomb. He became Mr. Freshman, part of Howard’s Royal Court that promotes campus leadership, representing the best of the best. He dedicated himself to protesting any perceived involvement by Howard with President Trump’s agenda or cabinet, creating the unaffiliated student group HUResist in the hopes of pushing Howard toward resistance against Trump’s more conservative educational doctrine. His freshman year wasn’t just a time of political activism — it was a time of personal growth.

“I was coming into my own identity as a queer person, I was around people who were more accepting,” said Ross.

He came out on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter in December 2016, something that his mother and church rejected at that time. But his pain was softened by knowing he would return from winter break to Howard, where he “had built a community."

While he had experienced depression before, coming out as gay produced new waves of anxiety and feelings of worthlessness. In the spring semester, he sought help from Howard’s counseling services, but without an immediately available spot, he was placed on a waitlist.

It all came to a head on April 23, 2017, the night of Howard’s Student Choice Awards, where Ross won Activist of the Year. That night, after celebrating with friends and drinks, the joy turned bitter. Eventually, Ross began vocalizing his desire to end his life. His friends grew increasingly concerned about Ross and decided to call campus police to get help.

Ross’s memories of that night are foggy. He remembers two police officers arriving, one putting him in handcuffs. He was escorted out of the dormitory and taken by ambulance to MedStar Washington Hospital’s psychiatric unit.

“My experience in the psych unit was traumatic. I was an 18-year-old boy, I had just come out, I was away from my family,” said Ross. A sympathetic nurse helped advocate for Ross and helped shorten his stay to three days.

Howard University.

Howard University.

A condition of his release was that Ross would return home to Texas to receive psychiatric support. So, Ross met with Howard’s student services, where he was told his only option would be to withdraw from his classes. Ross filled out his paperwork, and then returned home.

On May 12, Ross received a phone call from a Howard official, confirming that he had withdrawn. Ross did not get the name of the person he spoke to, something he would come to regret in the coming months, though phone records prove he received a call.

That July, as Ross debated where to continue his educational journey, he reached out to Howard to receive his transcript so he could officially restart classes, only to discover it had been placed on a hold.

Ross was confused. He had received a scholarship in the spring semester that covered the cost of any debts he had incurred that year, and he had the receipts to prove it. Once that financial mix-up was cleared and Ross finally received his transcript, he noticed that his spring semester courses were still listed. He had failed them, and now his GPA, which had been a 2.0 in his fall semester, was down to 1.3. Ross had not been withdrawn.

“That begins the long back and forth over the next year,” said Ross, saying that Howard’s explanations of why he had not been withdrawn changed frequently. “It went from, ‘the withdrawal was incomplete,’ then they said it was denied, then they said it was denied because it was incomplete — it looked like it sat on the dean’s desk and didn’t go anywhere.”

As he would come to discover, despite being led away in handcuffs by campus police, there was no official school record of the event. As far as Howard was concerned, Ross’s journey started on the same day he met with student affairs. If he had not discovered his own ambulance report years later, Ross said, it would appear as though the horrible night and days that followed never happened.

Ross took his experience and thorough paper trail to the D.C. Office of Human Rights, which found Howard failed to provide Ross “reasonable accommodation based on his disability.” Ross eventually brought suit against the university, which settled with him in October 2023. Terms of the settlement require him to present Howard with policy recommendations, which he hopes to do by the end of April. Ross said there is no guarantee that Howard will have to follow those recommendations, but he is determined that no one should go through what he went through ever again.

Howard said that, in the years since Ross’s incident, it has made changes to its mental health and withdrawal policies.

“The University takes our students’ safety and wellbeing with the utmost seriousness,” Howard University’s Office of Communications wrote in a statement. “The University understands the importance of investing in and providing resources to support the emotional and mental well-being of our students and is vigilant about responding to students’ needs in this area.

But two current Howard students attest to experiencing similar mental health difficulties to Ross, one in 2022 and the other this spring, 2024. One student, similar to Ross, was taken from their off-campus apartment in handcuffs after they called the police in crisis. Both students experienced suicidal ideation or attempts, and both were barred from physically returning to campus until they passed assessments from psychiatrists regarding their fitness to return. Although both submitted evidence that confirmed readiness to return to their studies, neither was accepted.

These students requested to remain anonymous, as they fear subsequent or retaliatory reactions from Howard which might prevent their graduating.

“I feel like Howard gives everyone a structure, and if your mold doesn’t fit that, it’s like, ‘oh well,’” said one student. “People don’t understand the depth of how mental health affects you on a daily basis. It’s every aspect of your life. My education is important to me, graduating is important to me. But it’s almost like, no matter how determined you are to get your degree or how much effort you put into it, it’s not seen or appreciated.”

Dr. Milton Fuentes, associate chair for undergraduate education and professor of psychology at Montclair State University, New Jersey.

Dr. Milton Fuentes, associate chair for undergraduate education and professor of psychology at Montclair State University, New Jersey.

Dr. Milton Fuentes, associate chair for undergraduate education and professor of psychology at Montclair State University, New Jersey, said there are higher levels of mental health concerns and distress at campuses across the nation.

A 2006 National College Health Assessment found that just under 50% of the over 94,000 students surveyed reported feeling “so depressed it was difficult to function,” and 9.3% had contemplated suicide. In 2022, the same group surveyed 54,000 undergraduates and found that 77% of students experienced some kind of psychological distress, varying from moderate to severe. A shocking 30% had experienced suicidal ideation.

“No campus is perfect, and there’s probably room to improve across the country,” said Fuentes. “If you look at the medical system, there’s more of a focus on physical wellness than psychological. It would be better if we thought about mental health and wellness in a holistic way.”

Ross’s suit bears great similarity to the 2023 disability discrimination suit brought against Yale University. The suit alleged that Yale practiced “systemic discrimination against students with mental health disabilities.”

Yale’s treatment of its students with anxiety, depression, or suicidal ideation had been under question for some time by both media and private organization assessments. The settlement “requires Yale to implement significant policy changes to increase equity for students with mental health disabilities,” said Megan Schuller, at the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, which advocates for full inclusion of those with mental disabilities.

Bazelon offers a model policy for colleges and universities to follow as a best practice for mental disability inclusion.

“Some schools lack comprehensive policies for responding to students with mental health issues or do so in discriminatory or punitive ways, requiring them to leave school or evicting them from college or university housing,” said Schuller. “Some charge students with disciplinary violations for suicidal gestures or thoughts. Such measures discourage students from seeking help. They isolate students from social and professional supports — friends and understanding counselors and teachers — at a time of crisis, increasing the risk of harm.”

In general, Schuller said that college student health centers or on-campus counseling simply do not have the resources or staff to meet students’ need, particularly for students looking to work with BIPOC or LGBTQ counselors.

Durmerrick Ross graduated from Texas Southern University.

Durmerrick Ross graduated from Texas Southern University.

In spring 2018, Ross was able to take his skills as a public speaker and make his way onto the Texas Southern University (TSU) debate team. He eventually finished his college journey there, despite starting with a 1.3 GPA. As a TSU student, Ross continued his activism, presenting legislation to the student government that would increase the number of counselors and funding to their department, though the legislation was never taken up to the school’s board.

For Ross, the journey to where he is now has been a long process of healing, one that he wants to share with others to prevent them from feeling the shame he felt for so long. Now that he has settled with Howard, he said it finally feels like he’s really graduated.

“Still, to this day, I have the deepest love for Howard. I love Howard and will forever love Howard,” said Ross. “That experience made me who I am. This fighter, activist, advocate, it’s literally because of the community I built at Howard. I am the student Howard says it wants and desires — you want students like me, the students who are self-advocates, empowered, and say the quiet things out loud, not taking mistreatment and injustice. These are Howard students.”

Liann Herder can be reached at [email protected].