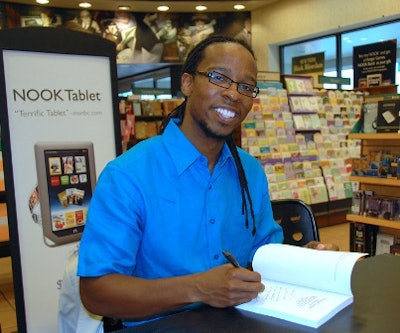

Dr. Ibram H. Rogers says he is “serious and passionate about using the lessons of the past to strive for a better present and future as it relates to race relations on campus.”

Dr. Ibram H. Rogers says he is “serious and passionate about using the lessons of the past to strive for a better present and future as it relates to race relations on campus.”In the award-winning book, The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstitution of Higher Education, 1965-1972, Dr. Ibram H. Rogers documents

the groundbreaking impact that African-American students had on U.S. college and university campuses through their activism. By demanding and protesting for Black studies, Black cultural centers, Black faculty members and respectful treatment, Black students challenged both historically White and historically Black institutions and inspired the ideals that American colleges and universities today strive for as they pursue 21st century campus diversity.

Rogers, a Diverse blogger and an assistant professor of Africana Studies at the University at Albany, SUNY, crafted this national study with records from more than 300 colleges and universities, including documents from 163 college archives. Recognized with the Diopian Institute for Scholarly Advancement 2012 Best Scholarly Book Award, The Black Campus Movement was published this past March by Palgrave MacMillan.

Recently, Diverse spoke with Rogers about The Black Campus Movement, his first book as a scholar.

DI — What inspired you to write about the Black Campus Movement?

IR —The short answer is that I became very interested in studying the first ever Black student union (BSU) at (what was then) San Francisco State College, which was founded in 1966. And it became very influential in terms of the founding of Black studies and even the Black Campus Movement in a larger sense.

And so I think through my research and interest in that original BSU, I of course began to grow interested in BSUs, student activism throughout that period and around the nation. So clearly just like when you study any topic you have to understand it in its larger context. The more I studied that larger context the more I became interested in that larger context.

I began to realize that what was happening at San Francisco State on some level was happening at campuses around the nation. And so I think people were knowledgeable on some level about what happened at San Francisco State, even though I think a book on that topic still needs to be written. But certainly people were not nearly as knowledgeable about the national social movement that was gripping colleges across the nation.

So, I felt there was an opportunity there for me to sort of fill that gap in the literature and in our historical memory.

DI — How has the book been received by readers?

IR — I think the book has been received quite well in terms of what I’ve heard and what I’ve seen. It was recently reviewed favorably in The Journal of Black Studies and that was the first major critical review. It’s been featured in magazines and newspapers. Scholars have contacted me (and invited) to come and speak on campuses about the book.

Several scholars have come up to me and have let me know that they are using the book in their classes. It sold pretty well. It reached a few top 100 lists on Amazon.com.

It seems as if it’s becoming very popular, specifically within Africana Studies and among those who are interested in the founding of the discipline. … I’m very pleased about its reception and some of the ideas that people are beginning to interrogate.

DI — How do you see scholars picking up on some of the history and ideas in the book and pursuing further research?

IR — One of the most obvious things that I did with the book is name this social movement the Black Campus Movement. And so, more and more scholars and students — doctoral students – are beginning to use that name to distinguish this movement from previous threads of Black student activism. And I think that is an interesting and great development. I think quite a few people have seemed to appreciate the first four chapters in the book, specifically chapters two through four, that really went into Black student activism prior to 1965.

People have contacted me and told me they were totally unaware of all of that student activism that happened in the twenties, in the thirties, the forties, in the fifties; they were totally unaware of the ways in which previous groups of students (had organized). One of the things that I argue in the book is that there were certain things that these students were demanding during the Black Campus Movement. But there were certain things they did not have to demand because those things had already been achieved.

I think people are really beginning to appreciate just the breadth of student activism – Black student activism — during this period because in the book I (document its occurrence) at hundreds of institutions. I think people are beginning to see just how massive this movement was.

DI — What surprised you the most in what you learned in your research?

IR — Certainly, students were active on many campuses. And so I was expecting documents and evidence of Black student activism at the major campuses. I’d expect to uncover it at Michigan State (University), but I didn’t expect to uncover it at Kalamazoo College or Michigan Tech, in the highest points of northern Michigan. I think the places, the suburban and rural historically White institutions, where I uncovered evidence of Black student activism really surprised me.

We’re talking about places in which there were 20 Black students, 10 Black students and those 10, 15, or 20 Black students took over a building or put together an organization or made demands that led to significant changes at their institutions far and extremely distant from their homes and Black population centers. That really surprised me.

It also surprised me that I knew, and scholars before me, had recorded specifically on campuses that students were demanding more Black students, Black faculty, and Black studies. But I did not know until I started uncovering research just how many students were demanding Black cultural centers on campus.

That, I argue in the book and I have argued subsequently, the demand for Black cultural centers was potentially at the same level as Black studies. And it was demanded that stridently, that passionately and that often (for) Black cultural centers and specifically at places in which historically White institutions were distant from Black population centers.

At those types of institutions, students were usually more than likely to demand Black cultural centers as their principal demand than Black studies. And that was a startling revelation to me.

DI — How do you characterize the influence of the Black Campus Movement on how it shapes the current diversity environment on college and university campuses?

IR — That was a central question that I had to grapple with as I began to conceive of the book. It is clear that there was a tremendous amount of reforms – racial reforms – that came into place as a result of this movement. But it is also clear that racism still pervades the academy in the 21st century. It is also clear that many institutions struggle with diversity.

And so I had to figure out how do I – as a result of those two seemingly contradictory developments — resolve that. So what does this mean? Specifically, what does this mean (in terms of the effect) the Black Campus Movement [has had] on higher education?

So clearly it did not eliminate racism; clearly, it advanced diversity but it did not eliminate the struggles for diversity. So what did it do? And it was that central question that allowed me to see that what it did was change the racial ideals of higher education, or what I call the racial constitution. It was those ideals that the Black Campus Movement shifted. (These are) ideals that are now encapsulated in one word — diversity — and to a lesser extent — inclusion.

And so before this movement, colleges and universities were not openly seeking to diversify. But through this movement they began to do that. Before this movement, colleges were not interested in multicultural education. So many of these different ideals were shifted during this movement so when we look at higher education today we look at a campus that values (diversity) on paper and in rhetoric. It clearly is an ideal.

But the question for our movement today (is whether) colleges and universities are living up to the ideals? And some are struggling to do that; some don’t care about doing that; some are paying lip service; some are striving and putting people into place to make it happen.

DI — Have you seen a response to the idea that today’s campus diversity agenda evolved from the impact of the Black Campus Movement?

IR — Those academics and administrators who are seriously interested in figuring out ways to diversify and eliminate racism on their campuses have actually reached out to me. In reading the book, they realized that I have some knowledge of this area and that I am serious and passionate about using the lessons of the past to strive for a better present and future as it relates to race relations on campus.

That’s been a positive development for the book because I’ve been able to speak to contemporary issues.

Of course, I’ve received a few invitations to speak about the current crisis in affirmative action because (it) came out of the Black Campus Movement, specifically at the campus level. You had the federal government, state governments, and student activism all pushing –pushing in different ways — for what is now called affirmative action.