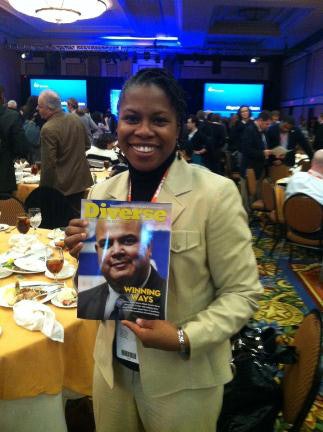

Jacquie Carpenter is the commissioner of the CIAA.

Jacquie Carpenter is the commissioner of the CIAA.

A century later, the CIAA (now the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association) is still around and is one of four NCAA-recognized conferences made up completely or predominantly of historically Black colleges and universities. The others include: the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, formed in 1913; the Southwestern Athletic Conference, formed in 1920; and the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference, formed in 1970.

At the time, the formation of an athletic league composed specifically of institutions designed for African-Americans made sense, if only as an extension of the logic that formed HBCUs in the first place. African-Americans were shunned from all of mainstream American life in the early part of the 20th century. And in the South, where the majority of Black colleges and universities were located, the Black community may as well have been on another planet.

More than a century later, however, much has changed in the country as a whole and at the institutions that compose the CIAA, SIAC, SWAC and MEAC.

The United States just re-elected a president, who 100 years ago, not only would have been limited to an all-Black institution, but he would not have been able to vote for himself. As a result of integration efforts that started in the Jim Crow era, institutions of higher learning are no longer allowed to discriminate based on race, gender or religion. And Black student-athletes are front and center at many of the institutions that would not allow them in the front door just 50 years ago.

It has been well-documented that Black institutions of higher learning, both state-funded and privately run, have been under-funded since their inceptions. Private schools had to rely largely on the pockets of White philanthropists, while state-funded institutions have traditionally received a smaller piece of the pie compared to their peer majority institutions.

“I don’t think if Alabama or Texas or LSU had been under-funded for a century, they would be in the position that they are,” says Dr. Dennis Thomas, MEAC commissioner.

Despite their financial struggles, HBCUs have produced some of the most talented athletes to ever carry a football or shoot a basketball. Prior to the late 1960s, and in some cases the mid-1970s, the overwhelming majority of Black athletes seeking to compete in collegiate athletics were restricted to Black colleges.

Former North Carolina Central football star and current Winston-Salem State athletic director Bill Hayes told ESPN in a 2007 article that in his day, playing for a majority institution was unthinkable. Especially in the South.

This race-based division was not necessarily a bad thing; it allowed smaller HBCUs an opportunity to recruit standout talent. For example, today Grambling State would have to compete with the likes of LSU or Alabama for the services of a future Hall of Fame talent like Willie Davis. Back in the ’50s and ’60s, Davis would have likely had to choose between either Grambling or Southern, but there was no chance of him landing in the SEC. The same with Florida A&M’s Bob Hayes, Morgan State’s Willie Lanier and countless others.

The story was the same on the basketball court. NBA all-time greats like Willis Reed (Grambling), Sam Jones (North Carolina Central), Bobby Dandridge (Norfolk State) and Earl “The Pearl” Monroe (Winston-Salem State) landed at HBCUs because few college basketball teams recruited Black athletes.

Today, however, change has come. A 2011 report by the NCAA revealed that 48.5 percent of Division I college football players are now African-American. The same report showed African-Americans composed 60.9 percent of all Division I basketball players. It doesn’t take a statistician to figure out that with just 24 HBCUs participating in sports at the Division I level, the majority of these athletes are now competing at majority institutions.

The impact of integration

While the increased opportunity for African-Americans to attend majority institutions and compete in athletics has been a positive development, it has had a downside, mostly for HBCUs.

When majority institutions began recruiting Black student-athletes en masse, HBCUs had to compete with schools that were significantly better funded, had better facilities and the advantage of television exposure. As a result, the talent pool drawn to HBCUs has decreased dramatically in the last 40 years.

New CIAA Commissioner Jacqie Carpenter knows first-hand the challenges facing HBCUs when recruiting student-athletes in the post-integration world. She came to Hampton University in the late ’80s, specifically because she wanted to attend an HBCU. She knows that more often than not, that is not the case.

“It comes down to perception, because there are so many doors open,” Carpenter says of attracting top tier talent to HBCUs. “They don’t see HBCUs as an avenue to get the same exposure.”

Money as an un-equalizer

The challenges facing HBCUs go beyond the field of competition, especially in Division I. Last May, USA Today released a report detailing the revenues and expenses of Division I public schools from 2006 to 2011. Seven of the 10 schools ranked at the bottom of the list were HBCUs. Coppin State brought in just less than $3.5 million in revenue during the five-year period, yet it has to compete with schools like the University of Texas, which accumulated more than $150 million during the same time period.

The CIAA, by contrast, has had several Division II national champions in both men’s and women’s basketball. Earlier this month, Winston-Salem State became the first school in the conference to advance to the Division II national championship. However, despite its extremely popular postseason basketball tournament, it has been reported that the conference found itself hundreds of thousands of dollars in the red.

With such daunting financial realities combined with the fact that HBCUs have won just one Division I national title in football and none in basketball, some believe that HBCUs may be better suited for Division II.

It’s a suggestion that Thomas repudiates. He points to the fact that in three of the six instances where a No. 2 team has been upset in the men’s NCAA basketball tournaments, MEAC teams were to thank.

“I don’t put much value in the naysayers,” he says. “State-supported schools in the South were never adequately funded,” Thomas says. “But given the commitment and the determination, they still excelled.”

Both commissioners also expressed a commitment to diversity while maintaining their roots in serving the HBCU community.

In 2008, the CIAA became the first of the four HBCU conferences to admit a non-HBCU when it accepted Chowan University. It is a move that Carpenter says has worked well for both the school and the conference.

“It’s truly opened up doors,” she says of Chowan’s addition. “Chowan has been a great fit.”

While the MEAC has yet to add any majority institutions to its 13-member conference, it may only be a matter of time. Thomas says that the conference has had talks with non-HBCUs, but that the stars just haven’t aligned as of yet.

“We’ve looked at several [non-HBCU] institutions,” he says. “But for whatever reason, it didn’t come to fruition.”

Despite the challenges facing HBCUs and the athletic conferences they call home, Thomas is confident that they will be here for years to come.

“The goals and objectives will continue to evolve,” he says.