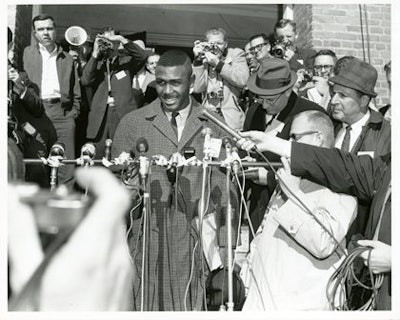

After desegregating Clemson, Harvey Gantt later in his career served as mayor of Charlotte, N.C., for two terms and is considered a living legend at Clemson.

After desegregating Clemson, Harvey Gantt later in his career served as mayor of Charlotte, N.C., for two terms and is considered a living legend at Clemson.When the walls of racial segregation in higher education in the South began to fall in the early 1950s, it signaled the end of an era in American society that would go on to shape the memories and experiences of many for decades to come.

In Texas, at what is now the University of North Texas; in Louisiana, at what is now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette; in Arkansas, at what is now Henderson State University; and a handful of other small institutions, integration opened new doors to Blacks in the region and set the stage for others to follow.

It was not until the early 1960s, when the larger Southern schools still holding on to segregation — Clemson, Ole Miss and Alabama — and scores of their lesser-known peers reluctantly surrendered to the future that the nation really took note. How could they miss it, given the political drama, racial strife and ofttimes hateful conduct that marked some of these final stands?

Today, as many schools celebrate desegregation milestone anniversaries, the impact in the post-segregation era feeds discussion and debate as educators and politicians wrestle to find clear answers to their questions about what desegregation and equal opportunity mean.

For sure, several generations of college-bound Black students and other students of color, particularly those excelling academically or athletically and sometimes both, have found wider opportunities in the post-segregation era. Their enrollment in traditionally White institutions (TWIs) in larger numbers year after year helped dismantle the so-called dual systems of state-controlled higher education. The trend spurred public and private institutions to embrace affirmative action efforts and disproved a widely-held myth that Black students could not achieve in TWIs.

The rapid growth of community colleges in the 1960s and 1970s, with less rigid admissions requirements and lower tuitions, provided even more high school graduates an opportunity to learn. A generation later came distance learning through online institutions, challenging the traditional campus and classroom approach to higher education.

As the expansion took root and diversity increased, a small but growing group of opponents of affirmative action emerged, charging that efforts since the 1950s were tantamount to reverse racism. They have since won some major court and voter referendum battles, chilling many efforts nationwide aimed at energizing what has evolved into diversity.

Today, leaders at public and private TWIs often find themselves walking on egg shells as they try to strike a balance between the past, present and future of a profound social change, the kind of change about which many segregation-era parents could have only dreamed, the kind that many post-segregation era opponents find offensive.

“Desegregation has created more opportunities to learn,” says Dr. Glen Jones, president of Arkansas’s Henderson State University, which in 1955, was among the first TWIs in the South to desegregate. “Now, the question becomes what will we do with these opportunities?” says Jones, a 1992 graduate of Henderson State and immediate past president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

State-controlled universities, never funded on an equitable basis in the segregation era, have also gradually seen their taxpayer support diminish in recent years as states abandon funding public education. The pattern has gone into high speed as state-funded education falls prey to budget cutters and new funding formulas based on educational outcomes replace the decades-old approach of providing a base amount of funding for each student seeking higher education.

A civil desegregation

When racial segregation was in its heyday in the old South, few schools reflected the region’s adherence to the rules and traditions of the region as much as Clemson University, South Carolina’s state-supported land grant college.

In January 1963, when Clemson conceded to the inevitable turn of events across the South and yielded to a federal court order to admit its first Black student — Harvey Gantt — the desegregation was noted for its civility only months after several days of chaos and violence at other old South icons like the University of Mississippi.

Today, Gantt, a Charleston, S.C. native who later in his career served as mayor of Charlotte, N.C. for two terms, is considered a living legend at Clemson. Scholarships and programs, including the Gantt Scholarship Endowment Fund, are named in his honor, acknowledging what he achieved and the tone and tenor set by him and the university’s top officials at the time.

As early as 1948, Clemson officials sensed the end was near, according to a historical account by Dr. H. Lewis Suggs, professor of American history at Clemson. Long before Gantt set his sights in high school on attending Clemson, the state’s top White politicians and higher education leaders had engaged in behind-the-scenes meetings and letters exploring how Clemson should deal with the coming ‘problem’ and avoid desegregation as long as possible. Gantt, and the students who followed him in subsequent years, solved the ‘problem.’

Blacks now constitute 6 percent of Clemson’s enrollment of nearly 20,000 students, a student body the university boasts now includes students of all races and from around the world. In addition to the Gantt scholarships and the Harvey and Lucinda (his wife and fellow Clemson alum) Gantt Center, the university has a chief diversity officer and several people of color in its ranks of professors. Last year, it appointed one of its Black professors of computer science to the first endowed chair in the state.

Meanwhile, Gantt helped the university mark the 50th anniversary of his admission with a convocation speech, one of several activities planned for the entire school year to recognize and celebrate the start of the university’s march into the future.

“Clemson has undoubtedly made progress toward being more inclusive,” says Dr. Leon Wiles, Clemson vice president and chief diversity officer, assessing where the university is today compared to the time when Gantt entered.

“But, we’re still challenged in faculty, graduate and undergraduate programs,” Wiles says, ticking off a short list of challenges ahead. The university president’s cabinet has only two people of color — him and an associate provost who is of Middle Eastern descent, he notes. “We don’t believe we’re where we should be,” Wiles says, adding that Clemson has a long way to go to be somewhat reflective of the state’s population.

“We’re actively recruiting in those areas.”

An era with no majority

From the looks of the campus landscapes at the sprawling University of North Texas in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, it is hard to tell this institution was once a legal battleground over keeping Blacks and other minorities out.

Today, UNT reflects the kind of diversity never imagined half a century ago, despite the state’s deep roots in Hispanic and Black culture.

Of its 36,000 students, 14 percent are Hispanic, 12 percent are Black and 5 percent are Asian. An assortment of other racial and ethic groups complement those minority groups and the 60 percent White student enrollment to give the university a modern-day look and feel of urban universities across the South.

That’s likely to change even more and soon, says Dr. Gilda Garcia, UNT vice president and chief diversity officer. There is not a racial majority in the university’s 5,000 student-plus freshman class. “We’re entering an era where there will be no majority,” says Garcia.

UNT’s evolution into a more open university stems from nearly a decade of desegregation efforts that culminated in 1955 with a federal judge’s injunction against the school, prohibiting it from denying admission based on race.

In February 1956, Irma Sephas became the first student of color to begin classes at the institution, according to a “History of Integration” recap by Nita Thurman published in The North Texan.

Thurman noted Sephas’ incident-free enrollment occurred the same day “a screaming, rock throwing mob threatened” Autherine Lucy as she entered the University of Alabama.

UNT’s evolution reflects the rapid change in demographics of the Dallas-Fort Worth area, the university’s primary service area, says Garcia.

In the area of employment, UNT’s situation mirrors that of most others across the region, says Garcia.

In its 2010-2012 report on tenured faculty employment by race, UNT showed 469 Whites, 66 Asians, 29 Hispanics, 22 Blacks and seven American Indians had achieved tenure. In the university administration, two of the institution’s nine vice presidents are people of color, including Garcia. In the president’s cabinet, three of 11 members are people of color.

Improving diversity in the ranks is essential, says Garcia, noting the talent pool for tenure candidates of color is small and competition for those posts is tough. Still, she says, “It certainly is a stretch goal. Our initiative is on increasing faculty diversity so it is in concert with our student demographics. I believe it’s achievable,” she says, echoing the pioneers who fought for desegregation.

Quietly blazing a trail

Had the political leaders and rank-and-file citizens of Chattanooga been as vocal as their counterparts in Alabama or Mississippi, Horace Traylor may have found his face and name in newspapers and on broadcast news programs across the nation when he tried to integrate the University of Chattanooga (UC), at the time a private, Whites-only university.

After all, it was 1963. Black neighborhoods around the city were being mysteriously bombed on a regular basis. Students were marching in downtown Chattanooga, as across the South, calling for an end to racial segregation at movie theaters, restaurants, places of work, in housing and on city buses. “Why not UC?” recalls Traylor, who in 1953, became the first Black student in Chattanooga to earn a college degree. He earned his B.A. at tiny Zion College, a small private college for Blacks. He would later become Zion’s president.

“When I was in this [registration] line, I said to myself, ‘We’re going to integrate this place,’” Traylor says, reflecting on his 1963 registration night at UC, where he would seek a master’s degree. He says he was so enthusiastic about the larger goal he was pursuing that for a moment, he had forgotten he was also trying to get a degree, he says.

Later that night, the director of admissions, whom Traylor knew, reminded him that UC did not admit Negroes. The next day, the chairman of the board of the university called Traylor asking if there was any truth to what he had heard about Traylor attempting to register. After a pause of bewilderment, he asked Traylor when he was going to apply again. Three months later, Traylor was enrolled in the university’s graduate school, studying for his master’s degree in education. Two years later, he became UC’s first Black graduate.

There was little drama, Traylor recalls, crediting the city’s mayor and officials at the university with maintaining their cool about his efforts.

On the first day, “I made a comment I was a rock star,” Traylor says, noting his admission was big news locally. “On the second day, I said it was normal. The students were so normal. No resentment from the faculty. There was no difference, although we all knew I was the first. The only time I knew I was a Negro was when I looked in the mirror.”

Traylor, who was appointed president of Zion College in 1959 at age 28, would continue his trailblazing education career in Chattanooga. In 1964, he managed the conversion of Zion into a public college. In 1965, while serving as president of Zion, he earned his master’s degree from UC. In 1969, while serving as president of Chattanooga City College, he was a key player in a three-way merger involving City College, the University of Chattanooga and the University of Tennessee. From that combination emerged the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

A few years after the creation of UTC, Traylor moved to Miami, where he became an administrator at Miami-Dade Community College. While there, he also earned a Ph.D. in 1978 at the University of Miami. Traylor, still hailed as a champion at UTC and all of Chattanooga, retired in 2009 as President of the Miami-Dade Community College Foundation, leaving it with assets of more than $200 million.

As for his trailblazing efforts since childhood in Chattanooga, Traylor today boasts of the gains made since he quietly made history in 1963. His barometer, he says, is what he reads in the literature he gets from the university on a constant basis. Blacks make up nearly 17 percent of the 11,667 member student body. Blacks have jobs throughout the faculty and administration, including the senior vice chancellor for finance, administration and technology.

“I think it’s on the right path,” says Traylor, whose pioneering efforts have been honored by the university with a scholarship in his name and other gestures.

Continuing the legacy

Glen Jones’ working-class family in Arkansas was determined their children were going to college, something they never got to do.

By 1988, when Glen was finishing high school, the higher education landscape was dramatically different from the one his parents knew as children. Black students who could go to college were no longer limited to three choices — Arkansas AM&N, Philander Smith College or any school out of state.

Educational opportunities were almost unlimited for their son. Financial aid was available.

Glen chose Henderson State University, a rural historically White Arkansas public school he had never heard of about four hours from home. It only took one visit to Henderson State to clear all other possibilities off the table, including historically Black colleges and their historically White counterparts, in and out of state.

“All were viable options, but Henderson just felt like home from the moment I stepped on the campus,” says Jones. “It had a great reputation for academic quality, and the people were incredible during my first visit to campus,” says Jones, who launched his career and helped his parents’ dream come true in 1992, when he graduated from Henderson State with a B.S. in administration and accounting.

“The young man who went out of (Henderson State’s) door four years later was not the one who entered,” says Jones, recalling that the faculty made sure that “when we leave, we’re ready for life.” In his case, that included the regular roster of academic challenges and some unexpected extras like providing him a tie for dress-up events and table etiquette coaching for dining out.

The experience made a profound impact on Jones, as he went on to earn a master’s degree, then a law degree in 1995 from the University of Arkansas, the same law school that several decades earlier tried its best to undermine the dreams of its first Black graduate — Washington, D.C. attorney George Haley.

Since Jones’ graduation, 10 relatives have gone to college, including six to Henderson State, where he became president in July 2011, bringing full circle a desegregation effort that began at the institution in 1955, when Maurice Horton enrolled as its first full-time Black student.

In addition to himself and other people of color in the faculty and administration, Henderson State’s enrollment of some 3,771 students is about 30 percent students of color, mostly African-American.

“Desegregation began the process of providing equal opportunity to everyone,” says Jones, immediate past president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE). “It’s created more opportunities for students to learn. Now the question becomes what will they do with the opportunities?”