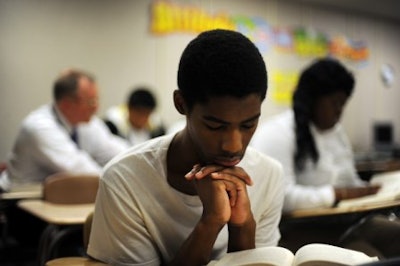

A new report examines practices that will promote success in AP courses for African-American students.

A new report examines practices that will promote success in AP courses for African-American students.Despite the push to broaden diversity among students who take Advanced Placement courses and exams, one of the oft-cited consequences, historically, is that overall pass rates for exams tend to decline. However, a small number of school districts have bucked the trend, according to a new report, titled The Road to Equity: Expanding AP Access And Success For African-American Students.

Released recently by the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, the report discovered that six school districts that increased or kept steady their participation levels in AP courses also saw their AP exam pass rates among African-American students improve enough to eventually catch up to their White peers.

The school districts were identified from among 75 considered eligible for the Broad Prize, which is awarded each year to urban school districts that demonstrate the greatest overall performance and improvement in student achievement while reducing achievement gaps among low-income and minority students. The six school districts were the Cobb County School District of Georgia the Fulton County School System of Georgia, the Garland Independent School District in Texas, the Jefferson County Public Schools in Kentucky, the Orange County Public Schools in Florida and the San Diego Unified School District in California.

The report says the Garland Independent School District and four other school districts experienced the same trend with Hispanic students.

If there’s a downside to the findings, it’s that the progress in the districts has been “glacial” in terms of pace, according to the report.

Indeed, the average increases in pass rates among African-American students in the six identified districts ranged from 1 to 4 percent from 2008 to 2011, and the increase in AP participation was from 0 to 1 percent during the same time period.

Nevertheless, the progress still shows what can be done when a concerted effort is made to prepare students for the rigor required to do well on the AP exams, according to Nancy Que, the author of the report.

“The pace is very slow, and we’re not saying that the war has been won by any means,” said Que, who oversees the data collection and evaluation process for the Broad Prize. “But there are strategies that have been consistent across the six districts that [other] districts should start replicating if we want to make progress on these issues.”

Among those strategies, Que explained, is “back-mapping” to elementary school the rigor that is required to handle college material.

“It means students are getting prepared for college-level content and higher order thinking when they’re young and not waiting until high school to start that preparation,” she said. Without such planning, Que added, participation rates in AP courses may increase, but the pass rates will not.

In the Jefferson County Public Schools, the path to progress began over a decade ago when district leaders attended a workshop offered by the College Board — creator of AP — that encouraged school administrators to search for the “hidden potential” of students to pass AP exams based on the PSAT score, said Robert J. Rodosky, executive director of the Data Management, Planning and Program Evaluation Division of Jefferson County Public Schools.

“We came back from the conference and said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna test all sophomores with the PSAT,’” said Rodosky. “That was sort of the initial foray in the loosening up of the requirements.”

According to Rodosky, previous “barriers” on who got into AP classes, such as GPA and teacher recommendations, have been shown to be inaccurate predictors of success in AP.

Rodosky said the district has also devoted more resources to AP. This past year, for instance, the district went from 199 AP teachers to 212. It also went from offering 368 AP sections to 401, all without increases in expenditures.

The increase in AP teachers and courses has mostly been in schools that “ten years ago wouldn’t have even thought of having AP,” said Rodosky, referring to schools with higher proportions of students in poverty.

Rodosky said the increase in AP courses will make an impact in the world of higher education. He said the district has begun to track its college enrollment and persistence rates in recent years, and the preliminary results look promising.

His office provided figures that show the percentage of students going to college increased from 62.9 percent for the Class of 2005 to 65.1 percent for the Class of 2010, then dipped down to 63.3 percent for the Class of 2011.

Each class has gotten successively larger from 5,115 in 2005 to 5,881 in 2010 to 5,922 in 2011, so overall, the number of graduates going to college has gotten larger.

“It looks like we have more kids staying in college, and it looks like we will have more kids graduating eventually within six years,” said Rodosky.