In 1974, Dr. James W. Loewen authored the history book, Mississippi: Conflict and Change, but had to sue to overturn rejection of implementation of the book in the state’s high school system by the purchasing board.

In 1974, Dr. James W. Loewen authored the history book, Mississippi: Conflict and Change, but had to sue to overturn rejection of implementation of the book in the state’s high school system by the purchasing board.

On the first day of the semester, the Harvard-trained sociologist posed a basic history question to his students at the HBCU: define the period in U.S. history known as Reconstruction.

While the students’ answers ran the gamut, the overall response boiled down to something like this — Reconstruction was the period after the Civil War when Blacks, newly freed from slavery, assumed leadership positions in government, screwed up and Whites were subsequently called in to save the day.

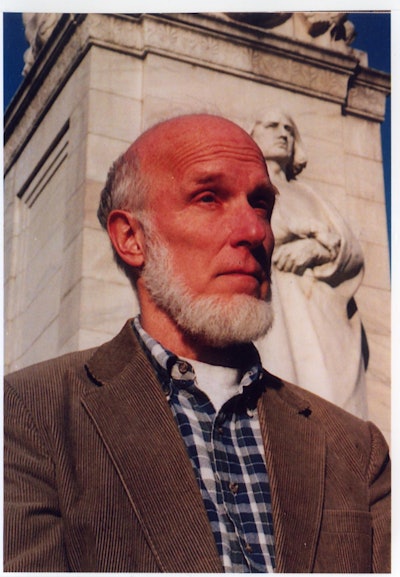

“I was stunned,” confesses Loewen, recalling that day as he sits comfortably in the living room of his Washington, D.C., home, just a few blocks from Catholic University of America.

“How hurtful this could be [that] the one time African-Americans have taken center stage in American history, and [they] believe that [they] screwed up? What does that do to your psyche?”

Loewen quickly came to understand that his students were typical products of a deeply flawed education system that paid little attention to the accomplishments of African-Americans. As desegregation slowly began to take hold across the Magnolia state amid fierce resistance, Loewen was even more convinced that high schools across the state had done a lackluster job in educating its students about not only the state’s history, but African-American history in particular.

To validate his conclusions, he canvassed high schools and witnessed firsthand how high school teachers followed the required history textbooks unquestionably.

Angered by what he encountered, Loewen tried to convince several history professors to write a new textbook to counter the myths and outright distortions. But when that proved unsuccessful, he applied for a grant, solicited a small army of Tougaloo students to be his researchers and in 1974, authored his own history book, Mississippi: Conflict and Change, which sought to clarify the inaccuracies while providing a factual narrative of the state’s turbulent past.

First Amendment battle

Even though his textbook was well received when it was piloted among White and Black students at different high schools in Mississippi and was the recipient of the Lillian Smith Award for Best Southern Nonfiction, it was quickly rejected by the state’s textbook purchasing board, whose chief responsibility is to approve all textbooks used in the state. The board argued that Loewen’s depictions of slavery in the state — most notably his decision to include an image of a lynching — was too horrific for high school students to stomach.

In response, Loewen filed a lawsuit against the board. Judge Orma R. Smith of the U.S. District Court ruled that the rejection of the textbook by the state board was not based on “justifiable grounds” and that Loewen and the other contributors had been denied their right to free speech and press.

“That whole escapade showed me that history could be a weapon and could be used against you, and had been used against my students,” says Loewen, who left Tougaloo in the late 1970s after the university decided to allow the Army reserve officer training corps (ROTC) program on campus — a move that he vehemently disagreed with due to his position as a peace activist. He was offered a faculty position at the University of Vermont, where he spent twenty years teaching sociology and race relation courses to undergraduate students.

But it was Loewen’s experience as a faculty member at Tougaloo that convinced him that a broader book exposing the historical myths in U.S. history was needed. After a two-year fellowship in the early 1990s at the Smithsonian Library, where he studied and compared twelve American history textbooks that were widely used at the time throughout the U.S., Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your High School History Textbook Got Wrong was completed in 1995 and became an immediate best-seller.

Today, Lies has sold more than 1 million copies. Revised and updated in 2008, the book offers a sharp critique of existing books and a retelling of U.S. history as Loewen believes it should — and could — be taught. It has won the 1996 American Book Award and the Oliver Cromwell Cox Award for Distinguished Anti-Racist Scholarship. It has also made Loewen a sought-after speaker, regularly taking him across the country as he continues to be a favorite on the campus lecture circuit.

“Despite its title, it’s not a book that bashes teachers,” says Loewen matter-of-factly. “I try to wash the unwash. I continue to be astonished about what [students] know about the past that didn’t happen and what they don’t know about the past that did happen.

“I became aware that teaching bias history was a national problem,” he notes. “Mississippi exemplified this problem in a more exaggerated form, but it was a national problem.”

A progressive upbringing

Born in Decatur, Ill., to parents who held egalitarian views, Loewen enrolled in Carleton College in 1960 and eventually switched his major from chemistry to sociology. His interest in race relations piqued after he read John Dollard’s Caste and Class in a Southern Town, which examined life in Indianola, Miss.

While his peers were spending their junior semester studying abroad, Loewen headed to the Deep South in 1963, just a few months after James Meredith became the first Black to integrate the University of Mississippi. Loewen spent three months living and studying at Mississippi State University, which, at the time, had one of the best sociology programs in the state. But like most places in Mississippi, African-Americans were prohibited from enrolling. “That’s why I went there,” says Loewen, who had experienced racial integration growing up in Decatur.

It was during this time in Mississippi that Loewen began his own research on race relations, and met prominent civil rights leaders like Medgar Evers and Dr. Ernst Borinski, a sociology professor at Tougaloo who was a recognized academic figure and a fierce advocate for integration.

After he returned to Carleton, Loewen knew that graduate school was something that he wanted to pursue. He was accepted into a doctoral program in sociology at Harvard where he wrote a dissertation about Chinese Americans in Mississippi.

When Loewen graduated, he landed his first teaching job at Tougaloo and remained there, even earning tenure, until he left in protest following the decision to allow the ROTC program on campus.

But shortly after he arrived at the University of Vermont, Loewen became frustrated by the university’s efforts to attract minorities to campus. “I was dissatisfied, so I kept leaving,” he says, taking sabbaticals and short leaves of absences, during which, at one instance, he became director of research at the Center for National Policy Review, a non-partisan, public policy organization that was housed at Catholic University’s law school.

And then came Lies My Teacher Told Me, which was followed by 1999’s Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Gets Wrong, a book that also dismantles the myths and misinformation that Loewen believes too often passes for American history. Loewen is now working on the final book in the trilogy, “Surprises on the Landscape: Unexpected Places That Get History Right,” which provides best practices on how Loewen thinks history ought to be conveyed.

While Loewen is often labeled as a historian, he doesn’t mind the classification. But when he’s asked to define himself, he proudly calls himself a sociologist. “There is no doubt that I think like a sociologist,” he says. “I think sociologists are more critical and more likely to be muckraking then the average historian.”