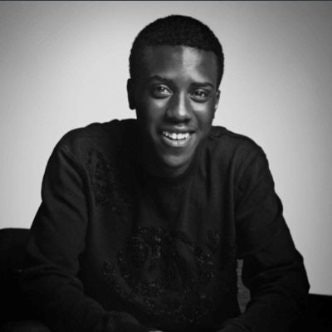

Jared Loggins is a senior at Morehouse College.

Jared Loggins is a senior at Morehouse College.Jared Loggins, a senior at Morehouse College, is choosing between Ph.D. programs. He plans one day to be a professor of political science. “The hope is to get a Ph.D. and enter into the professoriate—even considering how grim the job market is for professors,” he says.

He is willing to overlook the challenges that may lie ahead for two reasons. One, he

loves the field. And, two, he is acutely aware of how few Black professors there are relative to White professors. He says he hopes his voice and example might help tip the balance.

Loggins says that he was surprised by how many of his Morehouse classes were taught by White men. Their prevalence underscores the need for more Black professors across the board, Loggins says.

“African-Americans have worked extremely hard, and I know I’ve worked extremely hard, to be in a position to impact scholarly spaces,” he says. “That should be wholly reflected in the academy.”

While Loggins may not have expected to encounter so many White faculty at Morehouse, which serves a nearly 100 percent Black student body, the reality is that White faculty have always had a place at HBCUs.

Some, such as Lincoln University, were founded and staffed by White teachers and ministers from their origins in the mid-to-late 1800s onward.

Despite a long history with HBCUs, the White HBCU faculty experience is infrequently written about, and there are only a handful of studies available that might shed light on White faculty’s place within HBCUs.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) keeps tabs on the race and ethnicity of almost every HBCU. NCES provided Diverse with data for 99 HBCUs in 2013. At those 99 HBCUs, 56 percent of full-time instructional staff were Black, 25 percent were White, 2 percent Hispanic and 10 percent Asian.

By point of comparison, on the national level, 79 percent of full-time instructional faculty were White, 4 percent Hispanic, and 9 percent Asian or Pacific Islander, according to NCES data from 2011.

Only 6 percent of faculty were Black. Dr. Kimya Dawson- Smith’s 2006 dissertation is one of the more recent and comprehensive studies of White faculty at HBCUs. Her dissertation surveys White faculty at two HBCUs and looks at their place at the institutions from a historic perspective.

Ensuring a smooth “socialization” of White faculty at HBCUs is key to their success, she found, as they adjust from “majority” status to being “minorities” within a minority-controlled space.

Some of the greatest challenges that White faculty reported in Dawson-Smith’s dissertation are the barriers they encounter with promotion and tenure. Tenure requires publishing papers, but too often, they do not have enough time to write because they are caught up in the duties of teaching. Leadership positions, too, they find, tend to go to their Black colleagues.

Fighting criticisms

When speaking with White faculty about their experiences, one theme is clear: White faculty are reluctant to criticize HBCUs. Even when they do identify a problem, they tend to rationalize it.

Their concerns to speak freely stem from job security, they admit, but also a love for HBCUs and a desire to portray them in the best light possible.

HBCUs receive so much criticism, one White HBCU professor says, when really, there is so much to celebrate about them.

Take, for example, the idea found in Dawson-Smith’s dissertation that leadership roles tend to go to African-Americans. While this may be true to a certain extent, it also makes sense that HBCUs would be bastions of Black leadership.

After all, Black leadership positions were hard-won. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many HBCUs were governed by White administrators, who were reluctant to relinquish control.

Howard University did not have a Black president until 1926, nearly 60 years after it was founded. Lincoln University, the nation’s first degree-granting historically Black university, did not see its first Black president, Dr. Howard Mann Bond, until 1945, close to a century after its founding in 1854.

“If you think about HBCUs, these are places of historic models of Black success,” says Dr. Derek Greenfield, who taught at Alcorn State, Shaw and St. Augustine’s universities. “It’s so important, I think, for students and for employees to have access to spaces of incredible Black achievement, in a society that often devalues their existence and their greatness.”

Even though leadership roles tend to be held by Black staff, White faculty and staff say that, if they felt driven to seek out leadership positions, they would have made that their career goal. But they sought out their jobs at HBCUs because that is where they find the most fulfillment—teaching is their vocation and passion.

Or, in some cases, digitizing old archival collections is their passion.

A White, former Lincoln University librarian, Dr. Susan Gunn Pevar, says that she was content with her work as a special collections archivist.

She says she noticed a perception among some of her White colleagues that permanent leadership positions at Lincoln tend to go to African-Americans.

“I really don’t know if that’s true, but it could be true,” she says. The question was of limited interest to her, since she did not plan to ever apply to be director of the library.

Alcorn as example

Still, active attempts to change the diversity profiles of schools can meet with pushback, as events at Alcorn State University just a few years ago would suggest.

More than 90 percent of Alcorn’s students are Black, and nearly 70 percent are female, reflecting yet another fundamental inequity in Black educational attainment in the United States. Black women outpace their male counterparts in terms of college completion.

Alcorn was the first Black land-grant institution, built in a rural corner of Mississippi to educate freedmen. In comparison to Northern schools such as Howard and Lincoln, Alcorn has a long history of Black leadership stretching back to its founding in 1871.

Today, Alcorn’s main campus is situated in what past Alcorn president M. Christopher Brown II calls “splendid isolation,” in the tiny town of Lorman, Miss., in Jefferson County. There is only one way to get there—down a 6-mile stretch of rural country road.

Jefferson is one of the poorest counties in the country and home to the greatest percentage of African-Americans in the entire United States.

When Brown began his presidency in 2010, he planned to raise Alcorn’s profile well beyond its rural corner of Mississippi.

“My goal for Alcorn was not to be a great HBCU, but a great university,” he says.

He set about raising the diversity profile of the university’s student body, faculty and staff, making some controversial hires, including bringing in Jay Hopson, the first White football coach in the history of Alcorn and the entire Southwestern Athletic Conference.

Part of the impetus to diversify, Brown says, stems from Alcorn’s mandate to recruit and retain a student body that is more than 10 percent other-race, following the United States v. Fordice Supreme Court case.

The Fordice decision found that Mississippi’s public institutions of higher education were effectively still segregated, many decades after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case theoretically put an end to “separate but equal” systems of education for White and Black students.

Brown says that public HBCUs and public predominantly White institutions (PWIs) both have a responsibility to disestablish dual systems of education—one White, one Black. “I believe that all publicly funded institutions in a state should provide access to its citizens, period,” he says.

Beyond fundamental issues of equality, diversity is important for creating more intellectually vibrant campuses, Brown says. His philosophy is informed by his undergraduate experience at South Carolina State University in the early 1990s, when the now-beleaguered university had more resources to actively recruit other-race students, and the research of Dr. Sylvia Hurtado and Dr. Patricia Gurin at the University of Michigan.

“They ultimately found that diversity in the classroom incentivizes and creates greater academic learning outcomes,” he says of the Michigan professors.

Finally, Brown wanted to drive up enrollments by bringing students in from out of state. Under his watch, Alcorn’s student body grew to more than 4,000 students by 2011, the largest ever in the university’s history.

Even as Brown won accolades for his work on the national level, he knew he was creating what he calls “cognitive dissonance” for some Alcorn longtimers.

Some of his more controversial hires were publicized in what might be described as a defensive manner. For example, Brown told an ESPN reporter that he hid news about the Hopson hire from Alcorn’s media department, filling them in only minutes before his own public announcement.

“There was umbrage, to say the least,” Brown says of his efforts to shake up the diversity status quo.

His White staff members reported that some of their Black colleagues at times refused to shake their hands or even acknowledge their presence.

“They felt the weight of the work, of doing diversity-change work, just as I’m sure African-American or Hispanic faculty feel sometimes [at PWIs],” Brown says.

He says the most pushback toward his diversity work came from the staff and the older, more traditional alumni population.

So while his White administrators and staff encountered some moments of misunderstanding with Black colleagues, the faculty, White and Black, were more receptive to his diversification efforts.

“Because of the fact that many of them have been through doctoral programs, most of which are at predominantly White institutions, they also bring a different set of intellectual strategies for dealing with difference than you would find at the staff rank,” he says. “So I think you’d find the most welcome space for diversity in your faculty.”

Greenfield, whom Brown brought on as chief diversity officer and a professor, says that he admired Alcorn’s legacies and traditions, including the university’s long history of providing access to higher education for those who might otherwise be disenfranchised.

And even though Greenfield was recognized with accolades for his service, he does acknowledge that it was not all smooth sailing at Alcorn, at least at first.

“As a White male outsider, not from Mississippi, it does take time for others to get to know you, and understand your heart, and see the vision that [I] have, and appreciate what it is you’re about and why you’re there. I think it’s important for people to know that you don’t perceive yourself as the savior from outside,” Greenfield, now a fulltime speaker, says.

Though Brown’s efforts to raise Alcorn’s profile were recognized at the national and state level—Alcorn was named HBCU of the Year by the Center for HBCU Media Advocacy in 2012—Brown’s tenure unraveled in 2013. Alcorn’s overseeing board found that the university had spent almost $89,000 on renovations to the president’s house, without seeking alternate bids as required by state law. Brown abruptly resigned in December 2013.

Several of Brown’s more high-profile hires have since left, although Hopson, the football coach, remains. Greenfield was replaced with LLJuna Weir, a Black woman who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Alcorn.

Diversity strengthens HBCUs

While Alcorn may serve as a cautionary tale for HBCU leaders who want to change the nature of their school overnight, experts agree that HBCUs are strengthened by such diversity.

“One of the hidden benefits of attending an HBCU is that students who attend an HBCU get a far more diverse faculty experience than they do if they attend the average predominantly White institution,” says Dr. Andrew T. Arroyo, a White assistant professor of interdisciplinary studies at Norfolk State University. Arroyo is an affiliate at the Center for Minority Serving Institutions at the University of Pennsylvania, which is run by Dr. Marybeth Gasman, a professor of higher education. He recently wrote a book chapter published in the e-book Diverse Perspectives in College Teaching debunking a series of stereotypes about White professors at HBCUs from a 1976 article in The Journal of Negro Education, by Dr. W.I. Warnat.

“I always tell people that HBCUs have the most diverse faculty. They always have been this way,” says Gasman. “And at the same time, I do worry about the faculty becoming less and less Black.”

It’s certainly a concern, particularly when one considers the declining number of Black Ph.D.s who are entering the teaching profession in general.

Dr. Robert T. Palmer, an associate professor at Binghamton University and an HBCU expert, points out that even the HBCUs that serve a predominantly Black population are still culturally rich and diverse places.

“HBCUs are [intrinsically] diverse because there are many different subcultures of the Black population,” he says. “But those factors are never taken into account.”

Nevertheless, he acknowledges that many Black students are looking for racial diversity, not just cultural diversity, when they choose a college. “There’s been research that has shown that some Black students, unfortunately, are less inclined to enroll in HBCUs, because they perceive that the lack of racial diversification may be a handicap as they enter the so-called real world,” he says.

Loggins can attest to the power of an almost entirely Black college. Morehouse is economically diverse, he points out, and the college attracts students from all over the world. “I know I have benefited from being at an institution that is wholly committed to educating African-Americans and African-American men in particular.”

Catherine Morris can be reached at cmorris@diverseeducation.com. Senior writer Jamal Eric Watson contributed to this story.