In a world in which Black people are struggling with yet another grand jury’s failure to indict yet another officer at whose hands a young Black person was slain, the title alone — aggressive, pointed, somehow turning the tables and making “White folks” the “y’all,” the “other” population that needed to be “dealt with” for a change — seemed to serve as quiet affirmation for people of color across the diaspora of the fact that Black folks do indeed belong and are not universally the biggest problem facing society today.

Emdin, an associate professor in the Department of Mathematics, Science, and Technology at Teachers College, Columbia University, continued in this theme for much of the text. Though his book targeted those in K-12 education, many of the principles are applicable to professors and institutions of higher education as well. The students are affected by the same flawed pedagogies — “white folks’ pedagogy,” he calls it, which can be perpetuated by both Black and White instructors who “maintain a system that doesn’t serve the needs of” students of color (in the hood or otherwise) — and suffer the prolonged effects of always being treated as the problem.

“I am not painting all white teachers as being the same,” Emdin writes to clarify early in the text. “In fact, there are some people of color who engage in what [is referred to by Langston Hughes in The Ways of White Folks as] ‘the ways of white folks.’ However, there are power dynamics, personal histories, and cultural clashes stemming from whiteness and all it encompasses that work against young people of color” in classroom settings.

Sometimes it is just a failure of instructors to relate, to understand how students of color process emotions (including frustration and ebullience), how they perceive power dynamics in a classroom, the things an instructor does that discourages their participation and hinders their learning, that contributes to a persistent achievement and engagement gap for students of color. For many who do not have shared experiences or for whom those experiences are far removed from the personas they have worked to present in their current lives, this inability to relate creates “a context that dismisses students’ lives and experiences” in many of the ways that the lives and experiences of Black citizens across the country and across the world are being dismissed in a broader societal context.

Often people want to consider cases of discrimination in classrooms or on campuses or in the street or in the boardroom as isolated incidents, rather than considering the prevalence of the psychology that says that Black students, and Black citizens in general, are inferior or, for the ones on whom a narrative of inferiority cannot possibly be projected, need to be “saved” from their environments. As Emdin points out, the idea that Black students need to be cleaned up and given a better life “presumes that they are dirty” and “indicates that their present life has little or no value.” This presents what he calls “a problematic savior complex that results in making students, their varied experiences, their emotions, and the good in their communities invisible.” This reinforces a narrative that seems to be unfolding across the country that underscores the invisibility of Black lives and the irrelevance of the Black experience and allows those who wish to continue to deny the systematic disenfranchisement of people of color in this country the ability to avoid examining themselves as the problem.

Emdin suggests that merely increasing the number of Black instructors is not going to solve the problem. Instead, he offers that instructors of all ethnic backgrounds need to take a more individual approach to teaching that places themselves in the world of Black students, rather than trying to remain above it or as saviors from it. It involves understanding the framework through which students of color experience the world and process the things that are happening around them, engaging in dialogue that meets students where they are and shows concern for their humanity. He points to a “frustration with the structure of traditional classrooms and the difference between the context of the classroom and that of the world outside of school.”

Making a concerted effort to understand those differences and the differences in the ways things happen outside the classroom not only impacts students’ ability to learn and receive information inside the classroom but also makes for more effective instructors. Drawing from his own transition as a teacher from being instructed to be emotionally detached and rigid to finally being welcomed into the students’ world after playing a game of pick-up basketball one day, Emdin reflects, “the more deeply connected I became to the neighborhood where the kids came from, the more I began to understand the significance of context as a pedagogical tool.”

Similar lessons can be applied in every arena of American life — from higher education to corporate settings to police-community relations. Many in positions of power and authority are often instructed to be, at worst, emotionally detached or, at best, neutral to the circumstances surrounding the humanities of those they are seeking to serve — particularly people of color and particularly those from urban environments. But as the cries to recognize the relevance of Black lives in this country grow louder — from the streets of Cleveland or Charleston or Baltimore to campuses in Missouri and New England and Southern California — Emdin’s advice about how to more effectively serve students (people) of color is a reminder that recognizing their humanity is a critical first step.

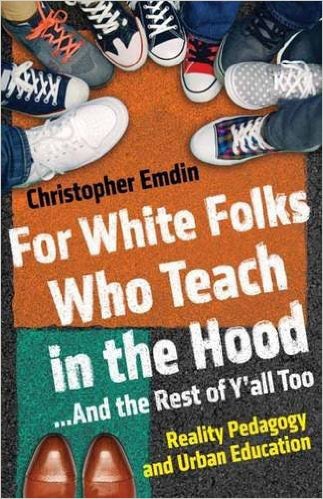

For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood … and the Rest of Y’all Too is scheduled for a March 2016 release. It can be preordered on Amazon.