Black History Month evolved from Negro History Week, which Woodson created in 1926 as a time to celebrate the contributions of African-Americans. He went on to establish the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 and the scholarly Journal of Negro History the following year, a periodical now published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) as the Journal of African American History.

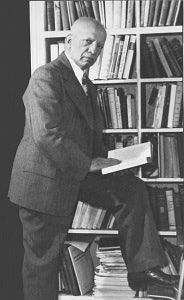

Dr. Carter G. Woodson

Dr. Carter G. Woodson

Yet, Woodson can’t be properly understood apart from his years in Appalachia and at Berea in eastern Kentucky, suggests Dr. Alicestyne Turley, director of the Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education at Berea and associate professor of African and African American Studies.

“There’s a lot of information about Carter Woodson’s time at the University of Chicago and Harvard, but not as much insight about him as an Appalachian and Berean and his early life in the region,” says Turley. “I was shocked to know he graduated from Berea because it was never publicized.”

That was in spite of her having served on a task force that worked to historically preserve Woodson’s home in Washington, D.C., where he had taught high school and later was a professor and dean at Howard University before his death in 1950.

Turley recalls colleagues being as uninformed as she was about the early chapter in Woodson’s history that included Appalachia and Berea.

“Often, that Appalachian part is left out,” she says. “When people discuss Woodson’s personality, saying he never smiled and was always about business and working, those are all Appalachian traits. So if you say you don’t understand Woodson, you could be saying that you don’t understand Appalachia. He was about hard work, commitment, honesty, integrity. Langston Hughes and some of the others who came after him said they couldn’t match him when it came to work. I believe that’s where his Appalachian culture shines through.”

Berea claims Woodson

Berea opened the Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education at Berea in 2012 to promote cultural and social change in keeping with the college’s motto that “God has made of one blood all people of the earth,” a New Testament biblical reference. Housed in the Alumni Memorial Building on Berea’s 140-acre campus, the center helps the college fulfill its mission “to assert the kinship of all people and provide interracial education with a particular emphasis on understanding and equality among Blacks and Whites as a foundation for building community among all peoples of the earth.”

It also furthers the inclusive mission of Berea as the first coed and interracial college in the South, whose White founder Rev. John G. Fee preached against slavery. Berea was intentional about diversity, equity and inclusion long before those concepts became mainstream in higher education, assembling racially integrated classes until a state law enacted in 1904 disallowed educating Black and White students together.

Today, Berea’s 1,610–student population includes a freshman class that is nearly 30 percent African-American, 12 percent Latino or Latinx and 7 percent international students, largely from Africa, according to Dr. Linda Strong-Leek, vice president for diversity and inclusion, associate vice president for academic affairs and professor of women’s and gender studies and general studies.

Students and speakers at a forum in the Woodson Center

Students and speakers at a forum in the Woodson Center

The student population – represented by 42 states, the District of Columbia and 76 foreign countries – is 58 percent female, 55 percent first-generation, 74 percent Kentuckian or Appalachian, 21 percent Black, 11 percent Hispanic or Latino or Spanish origin and nearly 12 percent international, according to school records.

The 164-year-old private college recruits and admits academically promising students who have financial need, covers their tuition and provides all students with a paid job as part of their college experience. One of fewer than 10 federally designated work colleges, Berea has 120 labor departments that give students work experience for a labor transcript that they earn along with an academic transcript.

Additionally, one-third of students in 2015 graduated with no loan debt while, according to the school’s latest figures, the average amount of educational debt upon graduation is $7,468.

The Berea model has inspired other institutions like Paul Quinn College, the small historically Black college in Dallas, to replicate aspects of Berea’s success.

The affordability and work component that have always been features of Berea College likely attracted Woodson, the son of former slaves and part of a large, poor family. He had informally taught himself while working as a coal miner before entering high school at the age of 20 and graduating within two years.

After briefly attending Lincoln University while working in tobacco fields, Woodson became a part-time student at Berea. He graduated in 1903 with a bachelor’s degree in literature and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in European history from the University of Chicago in 1908 and a Ph.D. in history from Harvard in 1912.

Keeping Woodson’s legacy alive

Programming at the center named in Woodson’s honor reflects Berea’s long-term emphasis on helping students succeed regardless of background.

For example, members of the campus community are encouraged to engage one another through a center initiative called True Racial Understanding Through Honest Talks, or T.R.U.T.H. Talks. The Black Student Center, Campus Life office and various student, faculty and staff groups collaborate to organize technologically interactive sessions that allow people to anonymously ask questions and get answers to sometimes-sensitive questions about race, culture and identity.

The intent is to foster interracial dialogue and nurture learners to become culturally competent citizens. Regular programs presented by the center include Diversity Peer Education Training workshops, a February Film Festival that focuses on issues of racial identity, a Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Celebration and “Conversations on Race” gatherings that have featured experts such as Dr. John A. Powell, director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at Stanford University, and noted feminist scholar and author bell hooks, Berea’s resident Appalachian Scholar.

And this year for the first time, the Civil Rights Seminar and Tour held every two years for faculty and staff is open to students. The hope is that by moving the summer bus trip to spring break and inviting students to participate without cost, historical civil rights sites they visit will seem more relevant to them, says Turley.

Dr. Alicestyne Turley

Dr. Alicestyne Turley

“Many of our students were not even alive at the time of the civil rights movement, so it’s an abstract idea,” she says. “A lot of faculty and staff are like the students. They’ve read about it or seen it on TV, but actually going to places where King worked or spoke or protested has a tremendous impact.”

The college encourages taking knowledge from theory to practice in much the same way that Woodson advocated approaching Black history.

“We believe in bringing all the elements together in a learning environment, and sometimes that means not being on campus,” says Turley, citing an off-site town hall on gun rights that the college organized last fall.

It can also be international, as when Berea junior Anne Otieno received a $500 grant to stage an educational workshop over the recent semester break for about 20 students in her homeland, Kenya.

“Woodson traveled to Africa and spent time there teaching, so why wouldn’t we support it?” Turley asks.

It’s all in a day’s work, says Turley.

“I’m always thinking about the racial history of America and how we have either progressed or not progressed the way the founders of the college thought we would,” she says. “It’s difficult to begin the conversation, it’s difficult to then act on the conversation and it’s even more difficult to change the conversation. So, I think about how to engage people in dialogue that nobody wants to have, and do it in a way that is nonthreatening and invites you into the dialogue.”

She adds: “I think you just have to be bold. And help people understand that by engaging others, you aren’t losing anything. In fact, you’re actually gaining something. It enlarges your world and perspective. Nobody loses by having difficult dialogue.”

Since arriving at Berea, senior accounting major Ben Christson has made some cultural adjustments that weren’t always comfortable, he confesses. The Ghana native, who came to the United States with his two younger brothers and father in 2010, lived on the east coast in predominantly White neighborhoods and had little interaction with Black Americans.

At Berea, his cultural lens widened as he participated in center programs and organizations such as the Black Music Ensemble.

“It was a way to expose myself to things, to widen my exposure,” says Christson, who manages the Woodson center. “I’ve been exposed to a lot on a lot of issues, and it goes far beyond what you learn in a classroom.”

Christson credits the academic and soft skills he learned at Berea with helping him perform well in an employment interview – well enough to land a job post-graduation at KPMG in Chicago.

“I kept getting questions about leading teams and working together,” he says, “and I was able to tie my answers into my work experience at Berea in the center.”

LaMont Jones can be reached at ljones@diverseeducation.com. You can follow him on Twitter @DrLaMontJones

This article first appeared in the February 7, 2019 edition of Diverse.