Four years ago, at George Mason University, Black students in the honors college started asking questions: Who were the slaves of George Mason IV, the 18th-century Virginia lawmaker whose name marks the school, and what were their lives like?

Those discussions turned into a research program, which culminated in the Enslaved People of George Mason Memorial Project, a plan to add monuments commemorating George Mason IV’s slaves in the center of campus next year.

“The lives and experiences of these individuals have just been, in some ways, erased or forgotten about,” said Julian Williams, George Mason University’s vice president of inclusion and diversity. “These were people. They were human beings, and they just happened to have been born at a time when they were enslaved. But they still have stories, and what we wanted to do is to help bring their stories to the forefront.”

In 2016, when students started to interrogate the legacy of the school’s namesake, history professors Dr. Benedict Carton and Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott were eager to foster students’ curiosity. They applied for an undergraduate research grant through the university to run a 2017 summer program aimed at uncovering the lost histories of the more than 100 slaves that George Mason IV owned.

Five undergraduates from different majors came together to tackle the project. They read 15 books over the course of two weeks to get a grasp on the history of slavery in Virginia before each student took on their own research focus.

Then, “we let them loose,” said Manuel-Scott. After trips to courthouses and archives, the group rejoined to present their findings and created a website to share them with the public.

“The types of questions that students were bringing to the archives created new discoveries because they were centering questions that centered Black lives and Black experiences,” she said.

Impressed with students’ work, the project was fresh in Manuel-Scott’s mind when she gave a keynote speech for incoming freshmen that August. When she mentioned the program in her address as an exemplar of undergraduate research, the university’s president at the time, Dr. Angel Cabrera asked for a meeting with the students.

They showed him around Gunston Hall, George Mason IV’s historic home, and “shared their dreams out loud,” Manuel-Scott said, to have their research leave a lasting mark on campus through a memorial. Then, “the stars aligned in the most beautiful way.”

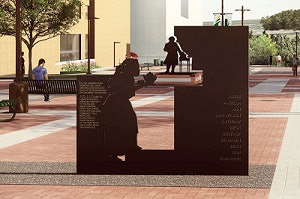

It so happened that the university was already planning a redesign for the center of campus, Wilkins Plaza. So, the memorial – designed with the help of architects, historians and public art experts plus student feedback – was added to the plans.

Manuel-Scott described the future memorial as “multiple moments of reflection.” Life-size bronze panels will commemorate Penny, a 10-year-old girl enslaved at Gunston Hall, and James, George Mason IV’s personal servant, with the names of other slaves inscribed. A statue of George Mason IV already on campus will be put on a brick base which includes a model of a brick found on his property with a slave’s thumbprint. It’ll also feature quotes that showcase the paradox of his writings about freedom and his slave ownership.

At a school like George Mason, where 40% of students are people of color, “so many members of our community have identities that have been marginalized or oppressed,” Manuel-Scott said. “A memorial can’t do all the work, but it is a part of the repair work. It is a part of acknowledging wounds.”

For her, the university is the perfect place to engage in that process of repair.

“If a university can’t do that, where will that work get done?” she asked. “Education is about asking those critical, complicated, messy questions.”

George Mason University is one of many higher education institutions currently wrestling with the moral faults of its paragons and past. For example, last year, after years of discussion and planning, the University of Virginia constructed a memorial to the enslaved laborers that built its Charlottesville campus. Georgetown University announced it would fundraise to offer reparations to the descendants of slaves sold by the school’s founders. Virginia Theological Seminary and Princeton Theological Seminary also created reparations funds to make amends for their institutional ties to slavery.

Williams emphasized that every university has its own history, so there’s no one-size-fits-all answer for how to contend with it. The self-reflection process for a school like George Mason University – founded in 1949 – won’t be the same as that of a university that profited from slavery or used slave labor on campus.

But every university needs to “ask tough questions,” he said. “Be brave. When we think about who we’re supposed to be as institutions of higher education, we have to ask these questions. We can’t be afraid of image or what will our donors say … Educational institutions, we should be on the right side of history.”

Sara Weissman can be reached at [email protected].