Dr. Jericho Brown first learned last week that he had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry at the very moment that the rest of the world got wind of the exciting news via a virtual announcement.

“I was home of course because everybody’s home, and I actually looked it up because I was trying to see it because I knew that they were announcing it that day,” says Brown, whose book, The Tradition — a collection of poems — had been nominated for the high honor. “The book did get some attention, so I knew it had a chance.”

Brown, who is currently an associate professor and the director of the Creative Writing Program at Emory University, was elated when they called his name, announcing him as the 2020 winner.

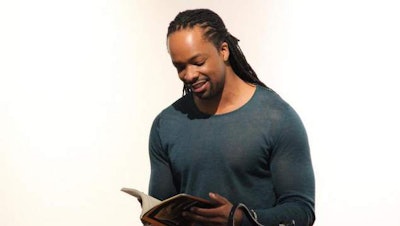

Dr. Jericho Brown

Dr. Jericho Brown“I’m just happy,” he says in a recent interview with Diverse. “I was excited, and I am still am. This is still brand new to me and it hasn’t fully sunk in.”

The Louisiana native is no stranger to receiving accolades for his poetry. The winner of an American Book Award and Whiting Award, Brown has also received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and the National Endowment for the Arts.

But flash back some twenty years ago, and Brown — a graduating senior at Dillard University in New Orleans — was preparing to graduate from the historically Black institution unsure about what he was going to do next.

“I knew I wanted to write, but I didn’t know how to go about making that happen,” he recalls, adding that Mildred Robertson, a former communications officer at Dillard, helped him land his first job.

“She saw me in the hall looking miserable and she said, ‘What’s going on?’ And I said, ‘I’m about to graduate and I don’t really know what I’m going to do,’” recalls Brown, who says that Robertson offered him a paid summer job in the communications office to hone his writing and public relations skills and, ultimately, figure out what he was going to do.

That summer experience opened up networking opportunities and Brown was eventually hired as a junior writer and rose through the ranks to ultimately became a speechwriter for Marc H. Morial, who served as mayor of New Orleans from 1994 to 2002. Morial is now the president and CEO of the National Urban League.

“When I first started at the mayor’s office, I was 22 years old and I noticed that all of the working people there had hobbies,” says Brown with a chuckle. “I had no idea that people actually had hobbies. They would come into the office talking about their tango class, or how they had entered the pie competition and I was like, ‘what!’”

Because he always loved to write, Brown enrolled in creative writing classes at the University of New Orleans with the goal of eventually earning a master of fine arts degree and perhaps teaching a writing class at Dillard someday. It didn’t take long, however, for him to realize that writing poetry wasn’t just a hobby; it was his vocation.

Brown later enrolled in a Ph.D. program at the University of Houston where he “fell in love with learning how to teach someone to write.” But the job as a full-time professor still wasn’t in his career plans.

“I love doing it. I know I teach, and I know that’s what I do, but it’s very important for me to think of myself as a poet first,” Brown says matter-of-factly. “And because I’m a poet, I teach.”

Poets, he says, are trained to mentor other poets. His teaching and administrative gig at Emory helps him “organize the mentorship that I would be doing anyway.”

Dr. Mona Lisa Saloy, a folklorist and professor of English at Dillard isn’t surprised by Brown’s accomplishments.

“While [he was] a student here, [Brown] wore business suits daily with a matching bow tie, along with his fellow male classmates aiming for the study of law. They were serious about school and worked hard,” she recalls. “Indeed, he had ‘that something,’ and I urged him to consider that perhaps he was sent here for something more than the law, that there was a fine writer buried inside of him, just waiting to be released.”

Brown, who is contemplating working on a book of personal essays and cultural criticism, says he is inspired by his own students who are serious about honing their craft.

“They pay a certain kind of attention to the news and the world and they’re interested in the difference between right and wrong,” he says. “They’re honest, sincere young people and they bring all of that care and concern to language and their writing.”

Jamal Eric Watson can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Twitter @jamalericwatson