When Meharry Medical College begins conducting COVID-19 vaccine trials in a few months, it will face a big challenge: how to inspire trust in the Black community that has reason to mistrust such interventions but stands to benefit the most.

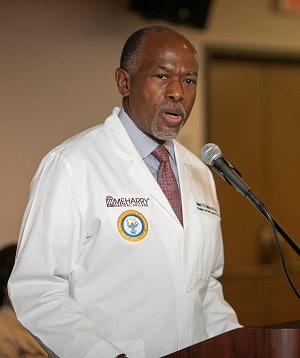

Dr. James E. K. Hildreth (Photo: Meharry Medical College)

Dr. James E. K. Hildreth (Photo: Meharry Medical College)It is a big “ask,” acknowledges Dr. James E. K. Hildreth, the president and CEO of the historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee. Yet, he said a successful vaccine is the best hope for African Americans and other people of color who remain the hardest hit by COVID-19. Now that Meharry is a part of the COVID-19 Vaccine Trials Network, getting them enrolled is a critical first step. And looking ahead to when a vaccine has been approved for widespread use, Hildreth said those most vulnerable for contracting the disease need to be ahead in line.

For now, though, Hildreth has no doubt that he and others at Meharry will need to work hard to dispel myths and allay fears among the local Black community who may trust Meharry with their care but not trust vaccines. “We’re starting to get inquiries” from those who want to volunteer, Hildreth told Diverse. But interest and curiosity need to translate into plenty of Black participants who are willing to roll up their sleeves, and for the Meharry leader, the best way to inspire trust is to lead by example.

“I’m going to be one of the first, if not the first, in line to get vaccinated at Meharry,” Hildreth said.

For the veteran and award-winning infectious disease expert, this was an easy decision to make.

“I don’t know a lot about a lot of things, but I know a lot about viruses and vaccines,” Hildreth said. “It’s hard to imagine how [vaccines] couldn’t be safe, especially when some of the old-fashioned approaches to developing [COVID-19 drugs] are being used. The science behind vaccines is very mature.”

Still, convincing Black people that they are crucial volunteers and that vaccines are generally “safe, have saved lives and don’t cause diseases will be a challenge,” Hildreth added. Black Americans are well aware of the infamous Tuskegee Experiment, which involved White, public health doctors letting unsuspecting Black men die from syphilis while withholding a drug that could treat them. Many also know about the case of Henrietta Lacks, a young Black mother in Baltimore whose cancer cells scientists and drug companies used for decades without her permission – and profited from them.

A poll conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research from May 14-18 found that 49% of Americans overall said they plan to get a COVID-19 vaccination when one is available, while 31% of respondents said they were unsure if they will get vaccinated. The remaining 20% said a flat “no.”

A participant’s race reflected some of the biggest differences in the poll’s findings. For example, Black Americans were more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to say they won’t get the vaccine if it becomes available. The survey also found that White Americans, more than any other group, were most willing to get the vaccine, outpacing Black Americans 56% to 25%. Of Hispanics, 37% said they will get a vaccine if it is available.

What will help encourage Black community members to volunteer for COVID-19 vaccine trials is the fact that Hildreth and many others who will be conducting the human trials at Meharry are Black. Black representation among researchers and those administering the tests will go a long way to build trust in Black communities and increase participation, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine told Diverse last month. “Having Meharry in the forefront on recruitment in the Black community is a really positive move,” said Dr. Namandjé Bumpus, a professor and chair of the Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences at the Johns Hopkins medical school.

Hildreth concurs with Bumpus’ assessment. “Meharry and Meharrians are trusted in the communities we serve, which have a history of abuse at the hands of America’s medical establishment. … We understand the subtle, yet critical cultural differences that have long been overlooked by mainstream providers, creating deep fear and distrust. … We can deploy quickly, we know where to go, and we will be welcomed,” he told a virtual convening of the House Ways and Means Committee in May.

Now, he’s working overtime to connect those most vulnerable to COVID-19 with a drug candidate that may be the best hope to protect them. It could likely be the first vaccine approved for use in the United States or globally. The candidate he’s referring to is AstraZeneca’s experimental COVID-19 vaccine being developed by research partners at the University of Oxford in England. With Oxford scientists out of the gate early on development, their drug is now one of only three COVID-19 vaccine candidates in late-stage Phase III trials, which, at this level, means scientists are testing whether it will be effective in humans. Most other vaccines being developed for COVID-19, Hildreth said, are still in Phase I and Phase II, testing for safety.

Behind the AstraZeneca-University of Oxford drug is the university’s “strong vaccine research footprint,” said Hildreth who recalls the robust research that was underway on a host of vaccines, including influenza, in the late 1970s when he was a graduate student at Oxford. Black people and those with underlying health conditions like diabetes and hypertension have been disproportionately ravaged by COVID-19. But they are exactly the ones who Hildreth is eager to recruit by the end of the summer for this and other drug trials. According to drugmaker AstraZeneca, it will start its vaccine trial with 30,000 people in the United States.

In addition to the drug being developed at Oxford, Meharry will make five other COVID-19 vaccine candidates available for human trials through participation in Operation Warp Speed, a public-private partnership the White House formed to fast track the development, testing and manufacturing of a vaccine to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In a pandemic, said Hildreth, “a COVID-19 vaccine will ultimately be the thing that allows us to get to a new normal and new way of life.”