In 1967, my third year at Grambling College before, in a nod to trendiness it became Grambling State University, the campus was roiled by an article in the Harvard Educational Review. Titled “The American Negro College,” its authors made several bold assertions, or more precisely broadside attacks against the integrity and legitimacy of Black colleges and universities, today commonly referred to as HBCUs.

Grambling was not alone in its reaction to the article. Administrators, faculty and staff, students and alumni at HBCUs across the country were deeply troubled by the article’s accusations, most of which lacked empirical support. Grambling had just begun hiring a few white faculty. Understandably, the article raised suspicions about white faculty: Why are they here? What are their motivations? Are they gathering information to write more vicious articles?

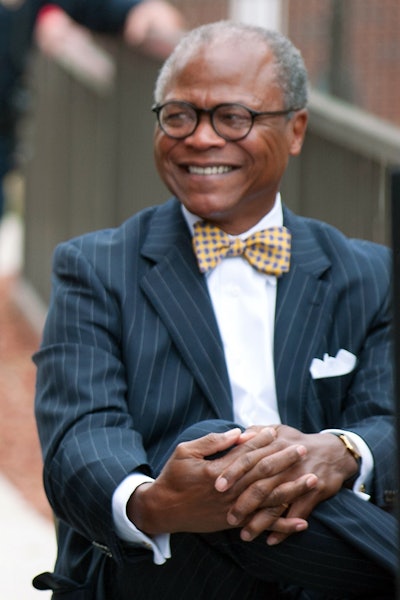

Dr. Alvin J. Schexnider

Dr. Alvin J. SchexniderI have held on to that monograph, studied it and re-read over the past fifty years. It is worn and dog-eared yet it continues to inform me. I credit this article with inspiring me to become a serious student of HBCUs, not as an alum with romanticized notions about Greek life and college sports, but as an area of intellectual interest and scholarly pursuit. The women and men who founded Black colleges and universities understood the gravity of the mission. Their immeasurable sacrifices are embedded in the fabric of every HBCU, each of which has a unique story to tell. Then as now, HBCUs must be taken seriously and it is incumbent upon leadership to exemplify as Dr. Michael Lomax, United Negro College Fund (UNCF) President wrote recently. In a thoughtful and informative Atlantic article Lomax made a compelling case for increasing support of Black colleges and universities. Countless others have made the case before but history informs us that biases are not easily reversed. Unfortunately, deeply flawed perceptions of “The American Negro College” persist.

Recent, so-called “transformational” gifts to HBCUs, most notably MacKenzie Scott’s multi-million dollar beneficence to twenty-two public and private HBCUs, present huge opportunities to reimagine and reposition some extraordinary institutions. No reasonable person can deny that these gifts with no strings attached represent a significant investment in these schools as well as an affirmation of their worth. They are not, ipso facto, transformational, however. These monies have the potential to be transformational only if meaningful conversations occur among institutional leadership, governing boards and stakeholders. Transformation will occur only if the recipient institution is strategic and intentional in the use of these funds. I admit to some reticence based on experience and research and I hope that institutional leaders and governing boards will take heed.

A major challenge confronting all of higher education is achieving effective board governance. There is a dearth of leadership talent among most sectors of society and higher education is no different. Sound leadership is essential in the presidency and on governing boards. As well, governance must be shared among institutional stakeholders. The top-down, authoritarian model of leadership characteristic of many schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries no longer works at the most respected research universities and liberal arts colleges.

In fifteen years as a board governance consultant I have never seen a university or college that is better than its board. Building an effective board is not unlike assembling the finest musicians to create a symphony orchestra. The talent may be there but it takes exceptional leadership to produce the desired results. Building an effective board falls on the shoulders of the board chair and the president. Together, they have the greatest influence in shaping board effectiveness. They also understand that irrespective of title—trustee, regent, visitor or curator—the fulfillment of fiduciary duties is paramount.

No president, however brilliant, visionary or energetic can lead by herself or himself. That is not to say that board governance intrudes on the executive role or vice versa. An effective board understands its role in assuring institutional oversight and accountability and appreciates the importance of strategic decision-making.

Board service is no longer honorific. An effective governing board is diverse and takes the long view and demands certain skill sets: knowledge of the academy, understanding higher education finance, technology, marketing and branding, fundraising and risk management, for example.

Recruiting and retaining high caliber talent to the presidency and to serve on governing boards of colleges and universities including HBCUs is a tall order, but it can and must be done.

Money alone will not cure what ails HBCUs and neither will it render these iconic institutions transformational. HBCUs are not monolithic. Some were in the process of transformation before receiving a multi-million dollar gift. Others may not be interested in transformation at all. For those that seek transformation funding may move them in that direction but that is not assured. And that is why the HBCUs that received recent financial windfalls recognize that transformation will not occur without intentionality and strategic choices. Otherwise, they will remain on a path toward survival when the goal must be sustainability.

Dr. Alvin J. Schexnider is a former chancellor of Winston-Salem State University. He is the author of Saving Black Colleges (Palgrave MacMillan 2013) and Confessions of a Black Academic, forthcoming.