Dr. Alvin Schexnider's father, Alfred Schexnider, and mother, Ruth Mayfield Schexnider.

Dr. Alvin Schexnider's father, Alfred Schexnider, and mother, Ruth Mayfield Schexnider.

“It’s important to know from whence we came,” said Schexnider, former chancellor of Winston-Salem University and author of Saving Black Colleges. “The struggles that people endured to create opportunities that they themselves were never going to be able to do.”

In Mayfield and Schexnider: Portrait of a Family, Schexnider unravels past mysteries while connecting the faith and encouragement of past generations to the success of future descendants, how family sacrifices put children on the path toward higher education and successful careers, almost all of which began at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

“In a sense, my grandmother lived her life through her children. They fulfilled an ambition that she had, that her father had,” said Schexnider, recalling how his grandmother Arlene had to drop out of school when her father died, never getting the chance to graduate high school herself. Despite that, she sent three of her daughters on to Xavier University in New Orleans and Texas College in Tyler, two private HBCUs.

“Education was the key then and, I think, now. It’s the one great equalizer in society,” said Schexnider. “The sacrifices people made to create opportunities that they knew they would never enjoy. They wanted to create a better life.”

While living in Winston-Salem, Schexnider became acquainted with Maya Angelou, whom he invited to speak at the campus many times.

“She was fond of saying, ‘somebody paid for you,’ meaning, ‘somebody worked hard to create an opportunity for you,’” said Schexnider. “That was her way of reminding students that this is your opportunity to take advantage of. Somebody sacrificed mightily for you to be here.”

Schexnider’s father died when he was 20 and attending HBCU Grambling College, now Grambling State University in Louisiana. Of his seven brothers and sisters, only he and his eldest brother remain. The death of his younger brother Kenneth in 2018 gave Schexnider the motivation to reach out to family members, asking long unanswered questions and uncovering a treasure trove of photographs, records, and stories.

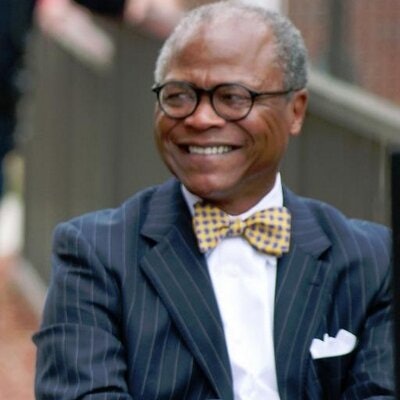

Dr. Alvin Schexnider, former chancellor of Winston-Salem University and author of Saving Black Colleges and Mayfield and Schexnider: Portrait of a Family.

Dr. Alvin Schexnider, former chancellor of Winston-Salem University and author of Saving Black Colleges and Mayfield and Schexnider: Portrait of a Family.

Schexnider was able to uncover handwritten notes taken by his father during an International Longshoreman Association Committee meeting held on March 18, 1961. The notes reviewed port operations in San Francisco and New York. Eventually, those observations would become the groundwork for containerized cargo shipment.

“This Black man in the 1960s was studying port observations that resulted in the implementation of greater automation, containerized cargo, which we take for granted now. He had a hand in it,” said Schexnider. “I think that’s huge when you step back and look at it. We don’t think of what we do as having a major role in the larger scheme of things, but he did. And if we look carefully at our own family history, what they were doing—that’s significant.”

Schexnider’s uncle Rufus Mayfield started his own dry-cleaning business and eventually became the first Black person elected to a seat on the Lake Charles City Council. Mayfield later became the first Black Chairman of the Lake Charles Housing and Redevelopment Authority. He advocated for the construction of a bridge to bypass train tracks causing major back-up in Black neighborhoods. After his death in 1996, that bridge was named in his honor.

One of the most challenging pieces of the puzzle to construct, Schexnider said, were the family trees, with some of the oldest charted family members dating back to the early 19th century. Weaving together the leaves of his family’s past made it clear, Schexnider said, that his own story is just another part of a larger mosaic.

“The number of people who had dreams for their children, their grandchildren—just dreams—they couldn’t imagine they’d be able to enjoy the things we take for granted,” said Schexnider. “There are so many opportunities for anyone who wants to go to college, wants to fulfill their ambition—I hope that this [book] stimulates and motivates people to say, ‘my great-great-great grandfather did this.’”

Liann Herder can be reached at [email protected].