In September, Dr. Ruth J. Simmons busily prepared to deliver the 2023 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. It was the latest on a long list of accomplishments in Simmons’ career as one of the nation’s most prominent Black women in higher education.

Dr. Ruth J. Simmons

Dr. Ruth J. Simmons

“I’m not known so much for my scholarship but more for my administration, so I find it a little perplexing, but a great honor,” Simmons says in an interview with Diverse. “I feel grateful for the role that the humanities have played in my own life, and I am passionate about what I think needs to happen with regard to minorities and impoverished children being exposed to the humanities, because I believe it makes such an immense difference in the way that they can construct a life.”

It’s that kind of thinking that makes Up Home so rich and compelling. In reconstructing her life story — detailing her humble beginnings from East Texas as the youngest of 12 children born in a sharecropping family to earning her Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures from Harvard University — one may get the sense that Simmons has not only wanted success and greatness for herself but for everybody.

“From the time I was born in East Texas to my retirement as the first Black president of an Ivy League university, my life has been marked by encounters with extraordinary people. I have not always recognized at the time the unusual character of my experiences, nor have I always been intentional in eschewing what I thought fate might have dictated for my life,” Simmons writes in the book. “Through it all, though, I have come to understand how rich and varied my life can be irrespective of the circumstances thought to dictate a certain path.”

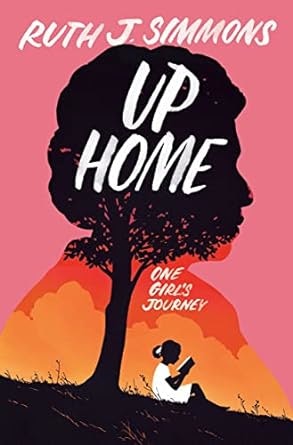

Dr. Ruth J. Simmons recently published her memoir, Up Home: One Girl’s Journey.

Dr. Ruth J. Simmons recently published her memoir, Up Home: One Girl’s Journey.

It’s an inspirational message from an inspirational woman who will go down in history as one of the most transformative leaders in higher education. And her impact on higher education cannot and should not be measured simply by being an historic first. She has appropriately been lauded and celebrated for her championing of initiatives designed to help minoritized students. During her tenure at Brown, for instance, she prompted a national conversation about slavery by examining the university’s ties to the transatlantic slave trade.

Simmons says the decision to write her memoir was prompted by the questions she received from students and others throughout the years. At the heart of those questions was a deep curiosity about how she overcame seeming insurmountable odds to become a world-renowned college administrator.

“I was troubled by the presumptions that people make about someone like me, born on the margins of society, desperately poor but able to rise to positions that are considered the most elite in this country,” she says. “I don’t want people to see a life’s journey as being baked into the circumstances of your birth.”

In the book, Simmons paints a beautiful picture of her mother, Fannie Campbell, who died from kidney disease when Simmons was just 15 years old. Her mother taught Simmons and her siblings what it meant to be a human being. That included to respect others and “never to hold ourselves above others.” Though she was poor, she gave generously to others and walked about the world with dignity.

“So many people walk about the world humped over,” says Simmons, who today owns the land she inherited from her mother.

When Simmons was named president of Prairie View A&M University in 2017, she thought it was odd that some questioned her decision to lead an Historically Black College and University. She not only attended an HBCU — Dillard University — as an undergraduate, but she served as provost at Spelman.

“I remember [the questions] and I was annoyed enough by them that whenever I went to speak, I began ruling out of order any question that suggested that while Brown and Smith [College] made sense to people, that my being at Prairie View did not, and I refused to answer those stupid questions,” she says. “Education is important. The students at Prairie View are no less important and their journey is no less important than students at Brown. And I don’t understand why people don’t get that.”

These days, she pushes back on how “idiotic this elitism is in higher education,” and recounts how some of her colleagues thought she had lost her mind when she left a position at Princeton University to head to Spelman in 1990.

“It seemed logical to me when I was asked to serve at Prairie View,” Simmons says. “Why would I not?”