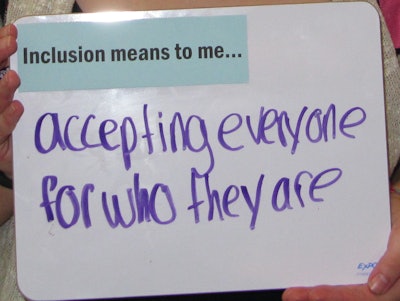

Student response at a Miami University Student with Disabilities Advisory Council event called "Inclusion Table."

Student response at a Miami University Student with Disabilities Advisory Council event called "Inclusion Table."

“It takes a lot of time to push for centers, or for things to be changed,” Simran said.

In fact, when she arrived at Duke in 2018, the student organization Duke Disability Alliance had been advocating for a cultural center for at least a year. Simran knew in order to convince administration and staff at Duke that a cultural center would be advantageous, she needed to show strong student support. So, she polled her fellow students and presented the results to Duke administration. Students, regardless of their ability or disability experiences, were in favor of the center’s creation.

By fall 2020, Simran received word that Duke had agreed, and the college would create a Disability Cultural Center on campus. It became only the tenth institution to do so in the nation.

Disability Cultural Centers (DCCs) are different from Disability Resource Centers (DRC) on campus. Resource centers manage the academic needs and accommodations of a student. Cultural centers are physical places (many virtual, during the pandemic) for students to connect with other students, faculty, and staff with disabilities and share their experiences, helping to build identity and a sense of belonging at their institution.

Rix did not end up attending Duke. Instead, he took the lessons learned from his sister and applied them at the University of Virginia (UVA), where he is a member of the Chronically Ill and Disabled Cavaliers (CIDC) student group. Together, Rix and the CIDC are hoping to create the eleventh DCC at UVA.

According to the CDC, 61 million adults in the U.S. identify as disabled, roughly one in four people. Their disabilities vary, from mobility to cognitive, to hearing or vision loss, or difficulty living independently. The number of disabled students on campus has been growing steadily since 2005.

The very first DCC in the U.S. was created in 1991 at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. It was created after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990. But it took over a decade for the next DCC to be created at Syracuse University.

“My understanding is we’re hitting critical mass of students and faculty, staff on campuses who are finding that disability services and resources, while helpful, are not imbued with the space for disability community and identity development,” said Jeff Edelstein, a board member of Disability Rights, Education, Activism, and Mentoring (DREAM), a virtual cultural center that’s part of the Association on Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD).

“There’s still a stigma [against disability], but the emergence and efforts of disability justice organizations have been able to promote disability ties to broader social justice,” said Edelstein. “We’re starting to see an improved representation and a recognition of the importance of that.”

The intersectional nature of disability lends itself toward partnerships with other diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) cultural movements on campus. But Edelstein said that disability is often excluded or only a minor part of an institution’s DEI office.

“The goal is never to replace another social identity, it should just be to broaden, deepen our understanding of other types of oppression and things on campus,” said Edelstein. “The hope is that [DEI officers] can be great allies, acknowledging how ableism informs other types of oppression.”

Elizabeth Anh Thomson

Elizabeth Anh Thomson

The students they interviewed for her study came from all levels of academic study. The only requirements were that they identified as disabled and attended events at their campus’s DCC.

“To know that their disability-positive identity was supported—it was huge. It reminded me of the other cultural centers where I worked,” said Thomson, who added that many disabled students, prior to attending college, did not have a connection with other disabled people, in their home life or friendships.

But DCCs are also unique as cultural centers, said Thomson, because they work to confront issues of ableism on campus, acknowledging the shifting lens through which scholars understand disability.

“Typically, in the past, disability has been framed as a matter of moral failures, your medical model, your religious model,” said Stephanie Dawson, the director of the Miller Center for Student Disability Services, the DCC at Miami University. “The emphasis there is the idea of a pathology within a person’s mind and body. This model sees [disability] as something medically wrong, to be fixed. We really embrace the social model and cultural lens, the idea that disability should be celebrated and is a part of human diversity.”

The Miller Center’s cultural events are guided by their Students with Disabilities Advisory Council. This year, the Miller Center ran a program called Miami Bound: Mastering Disability Access at Miami, where students with disabilities were invited to come on campus two days before the general student population. Students were able not only to connect with the Miller Center about their accommodations but were invited to share stories with each other about how ableism has impacted their lives.

Miami University has a disability studies program, and Dawson said the evolution of their cultural center gradually grew from there. When their physical space was updated just over five years ago to a more centralized location on campus, “it became easier for students to drop in and engage in the space,” said Dawson.

Dawson said a key to their cultural center’s success is the support of other diversity, equity, and inclusion leaders on campus. The cultural centers on campus work together to build programming, collaborating to be fully inclusive.

Kinshuk Tella made his decision to attend Miami University in part because of their disability center. Tella is studying environmental science and geology and expects to graduate in May 2023. Before coming to Miami, he had never had the chance to connect with his disability community.

“I grew up in Miamisburg, and I was the only blind person I knew I my life,” said Tella. “It was very isolating. I didn’t realize how isolating it was until I got into this club. I remember going the first time in August 2019. I instantly felt I was in a place I could be comfortable. I wasn’t the different one, the odd one out.”

Since then, Tella has become even more involved with the disability community, joining the National Federation of the Blind’s student division. His work there has led him to travel to D.C. to advocate for disabled rights.

Dr. Margaret Fink, director of the UIC DCC, said that disability cultural centers can help take their institution beyond mere ADA compliance. Fink’s DCC is located in old classrooms on their main campus, near the gender and sexuality cultural center, which makes collaboration easier.

“I think having space and energy for disability community and culture is really important, because universities are not easy places to be as a disabled person,” said Fink. “One thing that is helpful to recognize is that university culture is non-disabled. Even if you’re very well intentioned, that experience of not being anticipated or inaccessibility in various formats can be trying.”

Fink said that joining the disability community hasn’t just been transformational for her students, it’s been transformational for herself.

Stephanie Dawson, Director of the Miller Center for Student Disability Services

Stephanie Dawson, Director of the Miller Center for Student Disability Services

Events hosted at DCCs are not only offered to those students who identify as disabled. Rather, they are places where disabled and able-bodied students, faculty, staff, and alumni can gather and learn about each other. UIC’s DCC partners with an event called the Bodies of Work consortium, which brings a disabled artist into residence each semester to do student workshops.

The majority of DCCs were created by student activism, which, while effective at communicating the urgency of need, can make actualization of a physical cultural center a slow process. Undergraduate students have an average of four years to make an impact, and graduate students even less. And while AHEAD’s DREAM does offer a virtual community space for disabled students, Edelstein said it’s important for institutions to create their own cultural centers to the respond to the specific needs of their students.

“Some folks assume that because there are disability services and resources on campus, that’s sufficient. That we don’t need [DCCs],” said Edelstein. “There’s so much stigma, the importance of having the space to discuss [disability] openly is really huge. It brings us to the campus in a way we can’t ignore.”

Liann Herder can be reached at [email protected].

EDITOR'S NOTE:

A previous version of this article said the UIC hosted the Bodies of Work consortium. The consortium is hosted by Dr. Carrie Sandahl and Dr. Sandie Yi. Edit has also been made to correct that the DCC at UIC was not established due to their disability studies program.

![Screenshot 2024 06 05 141719[91541]](https://img.diverseeducation.com/files/base/diverse/all/image/2024/06/Screenshot_2024_06_05_141719_91541_.66613a2803b85.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=107&q=70&w=160)

![Screenshot 2024 06 05 141719[91541]](https://img.diverseeducation.com/files/base/diverse/all/image/2024/06/Screenshot_2024_06_05_141719_91541_.66613a2803b85.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)