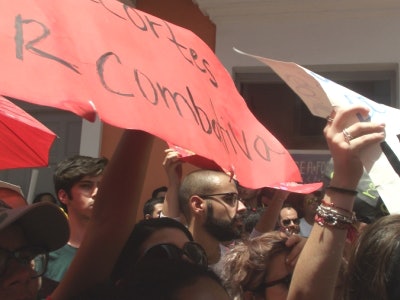

Last spring, students protested budget cuts by the University of Puerto Rico.

Last spring, students protested budget cuts by the University of Puerto Rico.Puerto Rico’s economic outlook is not rosy at the moment. The island is sinking under the accumulated weight of roughly $72 billion in debt and a declining population as inhabitants flee to the mainland in search of better jobs and opportunities.

The island is twice as poor as the poorest U.S. state, Mississippi, based on per-capita income, but the cost of living is 13 percent higher than in the United States, according to the Council for Community and Economic Research.

Due to Puerto Rico’s colonial relationship with the United States, with 3.6 million inhabitants and no voting power in Congress, its economy is by and large subject to the whims of U.S. interests. The economy is dominated by U.S. corporations that have the power to fix high prices for everyday goods. Puerto Rico famously has more Walgreens and Wal-Mart stores per square mile than anywhere else in the United States and the world.

For the past decade, the island’s economy has steadily declined. Now the situation is such that some have compared it to Greece and Detroit. Many believe the only options to resolve the current debt crisis are restructuring or default.

Economist and former United Nations consultant Jose Villamil said in June to The Associated Press that “the last four administrations have kicked the can down the road. At this point, there is no more can to kick. So we’re going to take some very strict measures and some very profound measures. It’s going to hurt, but there’s no way out.”

Educational lifeline

A strong system of education typically is a lifeline for economies, producing workers prepared to take on the needs of society. For Puerto Rico to rebound, at the most simplistic level, it will need educated workers.

Yet some are arguing that the island’s economic circumstances are so severe that the cuts are necessary and that public education cannot be spared. The island commissioned a report from former and current International Monetary Fund (IMF) staffers that was released in late June. Among other measures, the report advocated for reducing the Puerto Rican government’s subsidy to the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) and introducing needs-based scholarships at UPR, as opposed to the flat tuition rate all students pay now.

A group of hedge funds that bought up Puerto Rican bonds commissioned a report from former IMF consultants, who found that the island could begin to resolve its financial difficulties by raising taxes, selling off public buildings, laying off teachers and cutting back on education spending. Their report, which echoed some of the policies in the island’s report, came out in late July.

Cutting funding to the island’s public university, which enrolls the largest percentage of students on the island, is not a new idea. Last spring, massive protests roiled in the streets of San Juan as students demonstrated against Gov. Alejandro Garcia Padilla’s proposal to slash $166 million from the university’s budget.

Students and faculty at the university know that the economic crisis is still far from resolved. “I think that the crisis and its consequences are still to come. We haven’t totally felt its effect, although we are in the process of experiencing it now,” says Mikael Rosa, a first-year master’s student in social work at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras (UPRRP).

Rosa says that he hopes to use his master’s to work with children and young adults on the island but says that he may find himself forced to join the diaspora when he graduates. High unemployment rates are a major concern for him and his friends. They notice that many who do get jobs often can only find part-time work, without benefits like health insurance, or short-term contracts that offer little long-term financial stability.

“There are many young, graduated professionals who, once they finish college, they have to get on a plane and move to other places,” he says. “I don’t picture myself moving. I don’t want to. I’m hoping to stay here, in my country, but it’s a very difficult situation.”

UPR professors face other challenges. “The situation at the university is very tense,” says Alex Betancourt-Serrano, chair of the Department of Political Science at UPRRP. He says that, over the past two years, the university sustained a loss of $300 million in appropriations from the general treasury, the effects of which have been felt among the rank and file of the professoriate.

Providing a source of revenue

As one result of a reduced budget, Betancourt-Serrano says, when professors retire, the school cannot always afford to hire a replacement, leading to a reliance on adjuncts and part timers who cost the university less. In his department, most professors now have 35 students per class, up from 25 in years past. That also means the university pension fund will slowly be drained dry.

Professors such as Betancourt-Serrano say that it would be shortsighted to continue to cut spending on education. He is familiar with the hedge fund’s proposal to cut funding overall and is skeptical of its motivations. “Asking the advice of hedge-fund consultants or brokers regarding the well-being of a social institution is tantamount to asking for Colonel Sanders’ advice regarding the well-being of chickens,” he says.

The trouble with UPR is that its financial viability hinges on the economic prospects of the island as a whole. The university is unique compared to public universities stateside in that 68 percent of its revenue comes from the state. Most public universities in the United States derive a much lower percentage of their revenue from states and have instead upped tuitions.

Standard & Poor’s downgraded UPR’s credit rating at the end of June, stating, “a default, distressed exchange, or redemption of Puerto Rico’s debt appears to be inevitable within the next six months.” Bianca Gaytan-Burrell, director of U.S. Public Finance Ratings at Standard & Poor’s, says that all universities, public and private, can expect challenging times ahead. More recently, the agency also downgraded Puerto Rico’s private University of the Sacred Heart.

Gaytan-Burrell says that UPR and private institutions are heavily reliant on Pell Grant and Title V funding, meaning that the institutions are by and large tuition driven in terms of their sources of revenue. Over the past two years, universities saw their enrollments decline, but that decline sharpened in the fall of 2014.

“We believe that that really was accelerated due to pressure from the economy from the commonwealth,” Gaytan-Burrell says. “This is not just endemic to Sacred Heart, but we’re seeing it all around the island.”

For now, Pell Grants provide a stable revenue source for Puerto Rico’s public and private universities, but their Pell dependence could result in problems down the line. Any changes to how Pell Grants are awarded would therefore have a disproportionate effect on Puerto Rico’s universities.

Being Pell dependent also means that the universities have to keep an eye on their cohort default rates. If the cohort default rate exceeded 25 to 35 percent for two consecutive years, they would be open to sanctions from the U.S. federal government, including the loss of all federal funding. “They’re all working on getting the cohort default rate down, but if they don’t, they could lose Pell Grant and federal funding,” Gaytan-Burrell points out. Such an eventuality spells disaster for the universities.

The situation in Puerto Rico is clearly far from resolved. While Puerto Rico’s government appears to be gearing up to shake up the funding levels, there is a long history of student protest on the island. Last spring, students showed that they would not accept dictates from above easily. Rosa, for his part, says that he and other students are preparing to make their voices heard.

Catherine Morris can be reached at [email protected].