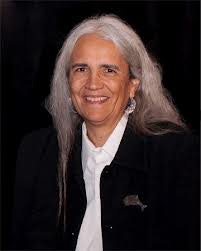

Abby Abinanti, a Chief Judge for the Yurok Tribal Court and a California Superior Court Commissioner, says that “no country can go forward with its students not successfully educated.”

Abby Abinanti, a Chief Judge for the Yurok Tribal Court and a California Superior Court Commissioner, says that “no country can go forward with its students not successfully educated.”The principal and superintendent of Loleta Elementary School in California’s Humboldt County grabbed a Native American student by the ear and asked, “See how red it’s getting?” The school secretary said students behaved like “wild Indians.” Native American students have been suspended for seemingly minor infractions ― breaking crayons and kicking a ball on a roof. Native American students are forced to finish their lunches, including having to drink spoiled milk while White students can throw out unfinished food.

These are some of the charges in a complaint filed with the Office for Civil Rights by the California Indian Legal Services, along with the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Center for Youth Law at the end of last year. The latter two groups also filed a federal lawsuit against the Eureka City Schools district charging that school officials discriminate against African American and Native American students.

The schools are in Humboldt County, a predominantly rural area, with one of the highest populations of Native Americans in the state ― around six percent. At Loleta, about a third of the students are members of federally recognized tribes, and Delia Parr, an attorney with the California Indian Legal Services, says because of the way these students are treated, many parents who were able to, have transferred their children to neighboring schools, leaving the most vulnerable behind. Parr says they filed this complaint because the school officials had ignored previous complaints, and this felt like the only way to effect change.

“Rather than recognizing that these children are members of this community, there’s continued disenfranchisement,” Parr said. “The school is not following the education code. … This just perpetuates the cycle for a community that suffers from historical trauma.”

Humboldt, in the far north of the state, has a bad record of sending kids to college, but it’s particularly abysmal for Native Americans, with fewer than 10 students qualifying for either California State University or the University of California system.

Having only single digits of kids ready for higher education ties directly to their treatment in elementary school, says Mat Matson, a member of the tribal council of the Bear River Band of Rohnerville Rancheria, who filed the complaint against Loleta officials, along with the Wiyot Tribe. Tribal leaders are trying to do everything they can to provide educational support for the children, such as running a resource library and offering tutoring, he says ― but they need the school to work with, not against them.

“The most egregious, disappointing, and shocking element of this is it appears to be a culture and a pattern that treats children differently,” Matson said. “When they are disproportionately suspended or punished, that undermines everything we’re trying to do.”

Matson acknowledges that as a small school, Loleta’s administrators have multiple jobs to do and responsibilities to carry out with limited resources.

“They probably face some unfunded mandate, and it’s difficult to meet all their obligations, but it doesn’t seem like there’s an effort to try to access pots of money available,” Matson said. “We’ve had many conversations with administrators, and it seems like there’s not an effort to get us to a solution. We want results, and we want some sort of path.”

That would include training school staff on the culture and history of the Native American students, he says.

That needs to happen at Eureka High School as well where the suit charges that, in a “wildly inaccurate and extremely insulting” lesson, a history teachers had students make up tribes and have them fight one another, saying that was how Native Americans resolve conflict. A teacher also asked a plaintiff in the suit, a Yurok girl, to explain a massacre of the Wiyot tribe, seemingly not understanding she was part of a different tribe.

“It’s easy when you have white Anglo teachers for them to teach what’s comfortable for them, which is their own history,” said Jim McQuillen, the director of educational services for the Yurok tribe. “People get uncomfortable when you talk about local massacres ― the Wiyots were massacred in 1860. That’s not so very long ago when you think of history.”

More negative history is even closer, McQuillen says, such as coerced boarding schools.

“There was this idea of beating the Indian out of the kid,” he said. “Our grandparents were forbidden to speak their native language and they got spanked or whipped for speaking it.”

McQuillen is very concerned about what he sees as Native American students being pushed out of regular schools to alternative schools that don’t prepare students for college.

That’s simply unacceptable, says Abby Abinanti, a Chief Judge for the Yurok Tribal Court and a California Superior Court Commissioner.

“No country can go forward with its students not successfully educated,” she said. “I want to see our kids get a fair shot. I believe in public education. I hope what will come out of this is everyone will recommit themselves to this system.”

Abinanti, like McQuillen, says the curriculum at the schools in Humboldt needs to change.

“If you go to school, and you walk away and go, ‘I don’t know anything about how to run a tribe, and I don’t know anything about me,’ that’s a problem,” she said. “Anything you learn there is not about us.”

Abinanti says often in the past the Caucasians and the Native Americans in Humboldt have ignored each another.

“They were happy not to see us, and we were happy to stay under the radar,” she said. “We have to say no more – it’s better for them and better for us. We live right next to these people.”