Released this week, “Creating Visibility and Healthy Learning Environments for Native Americans in Higher Education” describes a dismal reality for indigenous students seeking higher education and outlines corrective steps that institutions of higher learning can take.

The report stems from the Indigenous Higher Education Equity Initiative, a two-day August meeting in Denver hosted by the American Indian College Fund. The event convened leaders from Colorado State University, tribal and mainstream colleges and universities, non-profit organizations, foundations, institutes, associations and Native college students to craft a plan to increase visibility and promote college access and success for Native Americans.

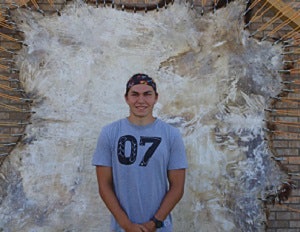

Foster Cournoyer Hogan

Foster Cournoyer Hogan

The initiative dovetailed with the Reclaiming Native Truth project last year by the First Nations Development Institute and Echo Hawk Consulting that explored public perceptions about indigenous peoples. It found that in spite of more than 1,000 tribes with five million members and growing, Native Americans are misunderstood and misrepresented at best and invisible at worst.

“Invisibility is in essence the modern form of racism used against Native Americans,” the report states. “It is this invisibility that leads to a college access and completion crisis among Native American students. When a student is invisible, his or her academic and social needs are not met. This leads to students feeling alienated and alone, derailing their matriculation and the realization of their dreams and potential.”

Being essentially erased, the report continued, “also prevents many young Native people from even thinking college is a possibility; others entertain the idea but are stopped from enroll in college because of negative experiences with admissions processes or on college campuses.”

Removal is another way of rendering indigenous peoples invisible, and that’s what happened to Thomas Kanewakeron Gray and Lloyd Skanahwati Gray last May, the report contends.

The Grays, members of the Mohawk nation, got lost on their way from New Mexico to a tour of Colorado State for prospective students. They arrived late and eventually caught up with their group, only to be detained and patted down by campus police after the mother of another touring student called 911 and said the teens looked suspicious.

By the time they produced proof of their identities and participation, the tour was over. The university later apologized; its vice president for enrollment and access, Leslie Taylor, served on the IHEEI organizing committee.

The incident “underscored the necessity that education leaders take action to increase the visibility of Native students’ experiences, stories, and lives in curriculum, on campus and in higher education research,” the report says.

The American Indian College Fund responded with a call to action because the agency “knew that it isn’t enough to provide Native students with access to a higher education,” said president Dr. Cheryl Crazy Bull. “We decided to use our expertise and to work with allies to make college campuses safer and more welcoming while raising the visibility of Native American students.”

Dr. Cheryl Crazy Bull

Dr. Cheryl Crazy Bull

Although 30.3 percent of the U.S. population over the age of 25 has a bachelor’s degree, that’s the case for only 14 percent of Native American and Alaska Natives in that age range, according to U.S. Census statistics. Meanwhile, 27.7 percent of the Native American and Alaska Native population is under the age of 18 – higher than the 23 percent overall, which has implications for college access and completion as those youngsters approach college age.

The report outlines eight key tenets, summarized by the beliefs that:

· Native students have a right to higher education and to attend any college or university they choose, and an inherent right to a place on college campuses that fosters their sense of belonging and importance in their campus community.

· Colleges and universities are duty-bound to recognize and acknowledge that their campuses reside on the original homelands of indigenous peoples; to incorporate indigenous knowledge for Native students to survive and thrive; to make visible, advocate for and empower Native students’ degree attainment; and to cultivate an ethic of care in supporting Native peoples by listening, learning and engaging with Native students, faculty and staff.

· Colleges and universities also have a responsibility to uphold tribal sovereignty by generating meaningful government-to-government relationships with tribal nations and tribal colleges and universities.

· Senior leadership at higher education institutions must make a commitment to do system-level work that benefits Native students’ college-degree attainment.

The report recommends numerous scalable remedies for each principle, such as creating and communicating to all campus guests “land acknowledgments” regarding prior indigenous occupancy; evaluating campus names and mascots that “reinforce racism and White supremacy” and removing “harmful vestiges of the past” to create more welcoming campuses; increasing Native professors and administrators across the board; enriching academic programs by including indigenous history and culture; and creating a social and academic space for Native students staffed by Native people who understand their challenges.

It also calls for forming campus committees and groups to better understand Native students’ needs when creating policies and programs that affect them; improving institutional data about and providing meaningful financial assistance to Native students; considering tuition waivers for Native students in states that took Indian land to give to land-grant schools; and senior leadership taking a systems-level approach at senior leadership levels that holds the entire campus community accountable for an environment that supports Native students’ success.

Foster Cournoyer Hogan, a sophomore at Stanford University from the Sicangu Lakota Oyate, Rosebud Sioux tribe in South Dakota, said participating in the gathering inspired him and allowed him to hear from Native scholars and make new connections.

The Native American Studies major said that living in a Native-themed house at Stanford this year with other Native students has enhanced his college experience. But it often feels “exhausting” being the only Native student in a class and having to educate others inside the classroom and out, whether it’s the omission of relevant indigenous contributions or classmates who compare his ritual sage-burning to marijuana, he said.

“I was one of the only people in my tribe to attend Stanford up until this year,” he said, adding that the arrival of his nephew this school year has allowed him to provide the kind of guidance and camaraderie he wished he had when a freshman.

“I come from a small reservation in the Midwest, and going to the West Coast was crazy culture shock to me,” Cournoyer Hogan said.

During discussion at the Denver gathering, he recommended that colleges admit Native students from the same tribes in cohorts to lessen the feelings of isolation.

“I just hope that in the future, Native students are able to access the higher education they want while feeling comfortable and also having support from their peers, faculty and the institutions themselves,” he said. “Higher education is a big thing for us. That’s what we need in order for our reservations to thrive. There are a lot of smart students who don’t have the support and opportunity to get higher education, and that’s so unfortunate.”

LaMont Jones can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Twitter @DrLaMontJones