Anthony Carnevale, director of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, cites said North Carolina’s program as one of the best at showing the value of a degree.

Amid the sluggish economic recovery, many families are wondering how best to make their increasingly expensive investment in college pay off. North Carolina’s public universities and community colleges have tried to provide an answer, by releasing the average salaries earned by students according to their major and campus.

A handful of other states, including Texas and Florida, have released similar data, and two-thirds of the states have received federal funding to track the progress of individual students from kindergarten to the workplace.

The figures may help sway students who don’t have a firm career plan, said Kelly Cravener, a 21-year-old marketing major at North Carolina State University. Her NCSU marketing peers who graduated in 2012 were earning almost $27,000 on average.

“I think a lot of people come in and they just don’t know what they want to do and they switch majors three or four times,” Cravener said as she scanned the web site outside the campus bookstore.

North Carolina’s website links student college records with salary information collected by the state’s unemployment agency. It shows what someone with say an anthropology degree is making after graduation and up to 10 years later. Students also can see a breakdown of the different salaries earned by anthropology graduates depending on which of the state’s 16 public universities they attended.

Federal funds linking data on individual children starting as early as pre-kindergarten to later earnings started during the Bush Administration and expanded with the 2009 stimulus package. The Obama administration and legislators, including Sens. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, and Marco Rubio, R-Florida, have pushed for more information about the benefit of particular degrees.

Despite rising costs, education beyond high school is one of the main differences between poverty and a middle-class lifestyle. North Carolina officials said they hope their data will help students match up with fields where pent-up demand will promise them high wages.

“Of course, there are many paths to success. So this is not a recommendation, it’s just a way to arm students and families with good, useful information,” said Peter Hans, who pushed for the project when he was chairman of the University of North Carolina Board of Governors.

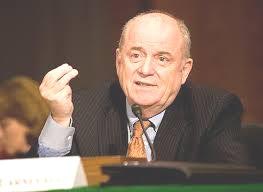

Anthony Carnevale, director of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce, said North Carolina’s program, inaugurated last week, is one of the best at showing the value of a degree. He expects college instructors to hate it.

“They don’t get up every day and think about getting somebody a job. They’re teaching history or something, so this is news to them,” Carnevale said.

Gabriel Lugo, a mathematics professor at UNC-Wilmington and president of the school’s faculty, said he discussed the website with four department chairs in both the liberal arts and the sciences at his university. They shared concerns about how the data will be used by policy-makers allocating state resources, he said.

“It makes me very nervous,” Lugo said. “It makes the implicit assumption that the contribution of your education is the main or the only factor affecting your earning potential. We all know that it’s not the case.”

The degrees-to-dollars comparisons also don’t take job satisfaction into account, Lugo said.

The architects of the North Carolina program acknowledged a degree has value beyond income. And the data doesn’t track graduates who found work out of state, those who start their own businesses or those who enter graduate school. And past results are not a guarantee of future earnings.

Timothy Reid said his parents have always emphasized that he pursue what he loved and the money would sort itself out. The NCSU senior who is majoring in psychology (a degree that translated into $15,443 a year for 2012 grads) said that parental commitment was tested when his older brother decided to become a music major.

“But they stayed with it—if you love it, do it. He ended up being an accountant,” Reid said. “That’s how I was raised. I guess if I was (raised) differently—that it’s all about the money—I’d be a business major.”

Then, he’d stand to earn about $27,000.