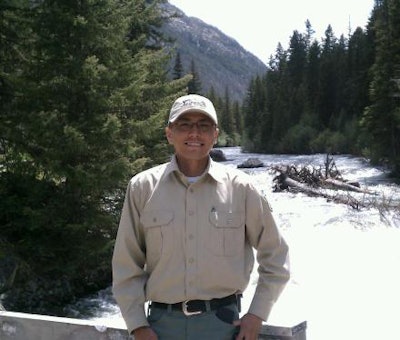

Student Dwight Carlston has helped tribal colleges recruit more American Indian males on reservations to further their educations.

Student Dwight Carlston has helped tribal colleges recruit more American Indian males on reservations to further their educations.When Dwight Carlston of Fort Defiance, Ariz., began his college career a few years ago, little did he know that he was doing a lot more than making his family proud by pursuing a college education.

While setting an example for his family, Carlston, now a 25-year-old environmental science major at Navajo Technical College with a 3.8 grade point average, was also helping tribal colleges throughout the continent in their efforts to get more American Indian males on reservations to further their education.

The ambitious efforts to recruit American Indian males are working, despite an abundance of hurdles, including lack of money to pay for college, few peer and mentor incentives, and important family obligations that don’t seem to leave much time for pursuits like college.

American Indian male enrollment at tribal colleges and universities has risen 19 percent in the past six years, according to the American Indian Higher Education Consortium. That translates into 5,807 male students out of a total tribal enrollment of some 18,400, according to AIHEC data.

“In the settings among indigenous people where you have to consider the cultural significance we serve, it is important to help male members,” says Dr. Elmer Guy, president of Navajo Tech. “It’s an important piece,” says Guy, echoing the sentiments of others.

“The men have been displaced,” explains AIHEC chair Dr. Cynthia Lindquist, president of Cankdeska Cikana Community College. She says the traditional role of native men on the reservation as “provider, gatekeeper, hunter” has gone by the wayside as the world around native men on the reservation has evolved.

Designing academic programs that draw on native historical ties to the land, such as the environmental science curriculum Carlston is pursuing, helps address the strong desire of many male students to strike a healthy balance between academic achievement and cultural values.

To address the sense of frustration and lack of self-worth among some native males, tribal colleges are also expanding their offerings beyond degree programs as they seek to address the needs of men in tribal college communities to redefine their roles in modern tribal societies.

These ideas address community needs, for sure, even if they don’t mesh with some national goals of graduating more students from college and having more earn advanced degrees in science, technology, engineering and math. It’s not that tribal schools aren’t pursuing those goals, presidents say; it’s just that those goals aren’t for everyone in a community.

At Little Big Horn College, for example, the Michigan institution has organized half a dozen short-term cohort programs aimed at males. The six-week introductory courses give students training in fields that can lead to work quickly: carpentry, welding, electrical work and operating heavy equipment.

At the end of their classes, they are ready for apprenticeships in their field of training, all aimed at helping the students get jobs and produce income for their families.

Setting up these kinds of programs and aiming them at males who are not college-bound “is important because, in a shorter time frame, they’re able to achieve some accomplishments,” says Dr. David Yarlott Jr., president of Little Big Horn. “They attain some kind of credential with each accomplishment; thus their worth increases,” Yarlott adds.

The Little Big Horn short courses are characterized as “stacking credentials,” as the school hopes the short-term exposure to college work will entice those who try it to come back and pursue their associate or bachelor’s degree in some area, based on a successful experience with a short course.

“It can be expanded into a flow college program,” says Yarlott, noting that the completion rate in the short courses over the past two years of the program’s life has been in the 85 percent range, higher than for regular classes.

“Our Native American males are a population that is desperately needed to continue their educational endeavors, whether that be in academics, vocations or workforce development,” says Dr. Pearl Brower, president of Ilisagvik College in Barrow, Alaska.

Like Little Big Horn, Navajo Tech and others, Ilisagvik extends its traditional degree-granting program to include short courses.

“Our Native American males are a population that needs to participate in this type of activity,” says Brower. “We know that people with more education are healthier and happier. If we can encourage our native men to take educational opportunities, rather than feeling like they have no options in life, entire communities will benefit,” she says.

“We know the tribal college not only provides an academic education, but it’s a whole transformative experience,” says AIHEC President Carrie Billy. “It changes the families.”

“Usually, if [non-college-bound men] try a class, that gets the ball rolling,” she says.

For Carlston, there were hurdles such as costs and personal considerations like proximity to family that were in his path. He is determined to finish the game, however, says the avid rodeo bull rider and one-time outstanding cross country runner.

Carlston recalls that most of his male high school classmates opted to go into the military after high school graduation or opted, for one reason or another, not to go to college. He wanted to continue his education, however, and have a better life for his family, noting that his mother worked two jobs to support him and his two younger brothers. His father had separated from the family years earlier.

After high school, Carlston worked construction jobs for a while to save money for college. He says he had not been told by school counselors of scholarships, grants and financial aid.

Once ready to afford college, Carlston started at Haskell Indian Nation University. After a year, he felt the need to be closer to family and decided to leave the Kansas institution and go back to Navajo country.

Navajo Tech was closer and ready, with a challenging academic program that also balanced Carlston’s desire to continue learning and his love for nature, which he acquired from his grandmother, who taught him about nature while they took the sheep out.

Carlston’s 16-hour course load includes studying environmental science, graphic systems, environmental law and engineering. Last summer he interned with the Yellowstone National Ranger District as a wildland fire fighter. Carlston says he likes being close to home and the challenge at Navajo Tech, although the rigors of college work have caused him to drop cross country running and significantly reduce his participation in bull riding at rodeos, a tradition that dates back two generations in his family.

“A college education is very valuable,” Carlston says. “It means giving us the opportunity to excel, to further yourself,” he says. “Just having the opportunity to be what you want.”

President Guy, whose college also offers some short courses for non-college-bound men, echoes Yarlott and other tribal college community leaders in asserting the focus on men helps round out a serious need.

“You look at families, and, in order for families to be healthy, you need income,” says Guy. “All in all, it really comes down to ways to stimulate economic development in native communities. So we build programs that are affordable and closer to home.”