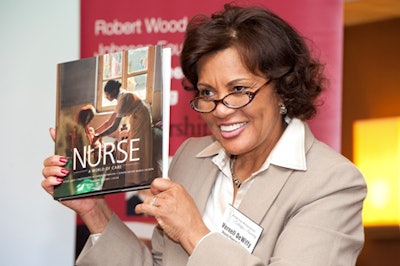

Dr. Vernell P. DeWitty, deputy director of the New Careers in Nursing Scholarship Program, says that faculty and administrators need to “see diversity in the profession as an essential part of their mission.”

Dr. Vernell P. DeWitty, deputy director of the New Careers in Nursing Scholarship Program, says that faculty and administrators need to “see diversity in the profession as an essential part of their mission.”

The shrinking nurse workforce coincides with the new reality that a greater number of the population is living longer, thereby increasing the need for health care providers. With urban and rural communities often lacking adequate health care, there is also a need for nurses who can effectively work with the country’s changing demographics. According to a fact sheet from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, the U.S. Department of Labor projects the need for more than 1 million new and replacement registered nurses by the year 2020. Leaders in the profession are actively promoting access to programs that will develop a diverse nursing population to fill both clinical and faculty roles.

“It is critically important to increase the number of nurses entering the profession from diverse backgrounds,” says Dr. Nancy C. Tkacs, associate professor of nursing and assistant dean for diversity and cultural affairs at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. “Patients feel greater confidence, trust and acceptance when they see nurses that resemble them in physical appearance and cultural characteristics.”

One approach to meeting that need is accelerated baccalaureate programs (B.S.N.). These accelerated programs, which take 11 to 18 months to complete, have existed for decades, but have only exploded in popularity in recent years. At the University of Pennsylvania, for example, the number of applicants has increased more than 94 percent in the past decade. Accelerated nursing programs are available in 43 states plus the District of Columbia and Guam. The programs are open to individuals who have already completed a bachelor’s degree in another field and fulfilled the requisite science courses.

Dr. Gail C. McCain, dean and professor at Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing in New York City, says they receive approximately 200 applications per year for the 30 available spots in the accelerated program. The minimum GPA for application is 3.25, but the applicants selected, who are virtually all people of color, have GPAs higher than 3.6. Hunter-Bellevue also has a higher percentage of men at 9 percent, versus the national average of men in the nursing field, which is around 6 percent.

“We know that, if we’re going to decrease health care disparities in this country, our nursing workforce has to reflect the U.S. population,” McCain says. “The accelerated program attracts people really diverse in terms of ethnicity, but also diverse in terms of background.”

McCain adds that these highly motivated adult learners also express interest in pursuing graduate level nursing studies and becoming nursing faculty.

“The average age of nursing faculty in the United States right now is 55,” McCain notes. “These students are a very good pool for us to grow nursing faculty.”

Dr. Vernell P. DeWitty, deputy director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s New Careers in Nursing Scholarship Program, indicates that the nursing profession needs to develop new leaders who can teach and train future generations of nurses that are fully equipped to meet the needs of America’s diverse population.

“We need to begin to influence and change the culture of nursing education and educators [so] that they really embrace the notion of diversity,” says DeWitty. “[Nursing faculty and nursing school administrators should] see diversity in the profession as an essential part of their mission in terms of educating future nurses of tomorrow.”

At the Pace University Lienhard School of Nursing, with campuses in Pleasantville, N.Y., and New York City, a program called “Grow Our Own” helps nurture future faculty from within the student body.

“We are taking individuals that are interested in clinical faculty roles and doing a huge amount of mentoring, trying to find people who are from diverse backgrounds,” says Dr. Harriet R. Feldman, dean and professor at Lienhard. “In Grow Our Own, we made an open call to our alumni of color. We told them that, in order to be part of this program, they need to be accepted to a research doctoral program.”

Two individuals have taken advantage of the opportunity. In exchange for their doctoral education being subsidized, they have agreed to work for a minimum of three years, full-time on a tenure track upon completion of their doctorates.

DeWitty notes that, in addition to increased demand for accelerated B.S.N. programs and the continual growth of such programs, there are also a growing number of accelerated master’s degree programs.

For the past six years, the New Careers in Nursing Scholarship Program has been providing scholarships for students from underrepresented groups who are enrolled in accelerated nursing programs. Given the packed schedule in accelerated programs, it is nearly impossible to have any kind of employment while in such a program.

“One of the things we’re hoping to accomplish through this scholarship program is that we begin to influence the organizational culture,” says DeWitty. Diversity would encompass not only diverse ethnicities but also diverse backgrounds and life experiences. “It increases the entire group’s ability to be culturally aware and culturally sensitive.”

One program that has received these scholarship funds is at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, which has a 12-month accelerated B.S.N. program that is mostly online. It attracts students in rural and remote areas and conducts many of the classes, as well as other elements of the program, in Second Life, a virtual world. Since the program’s inception, 18.6 percent of the students have been men.

Classes of 30 (out of approximately 150 applicants) are admitted twice a year — in May and October. The students, who come from widespread locations, come to campus on three occasions during their year of study. Students do their clinical work in local hospitals near where they reside with supervisors recruited and hired by the school and supervised by nursing school faculty.

“Our vision is to develop caring and scholarly leaders for contemporary and future health care,” says Dr. Suzanne Marnocha, professor, assistant dean and pre-licensure director at UW-Oshkosh. “I just hired two of our previous accelerated students that returned to graduate school to become faculty.”

The Fay W. Whitney School of Nursing at the University of Wyoming also has a significant distance learning portion to its accelerated program.

“We have, of course, our learning platform where we present our courses, but we also use video centers, podcasts, conference calls, … a variety of online tools,” says Candace Tull, associate lecturer and BRAND (Bachelors Reach for Accelerated Nursing Degree) program coordinator.

“The University of Wyoming is unique in that it is located solely in Laramie,” continues Tull. “Many people want a university education, but cannot move to Laramie. The BRAND program enables them to live where they live and still receive a quality B.S.N. education. Developing clinical sites is a challenge for every nursing school. This enables us to develop clinical partners with facilities throughout the state.”

McCain notes that, with implementation of the Affordable Care Act, approximately 33 million more people in the U.S. will have access to primary care. Nurse practitioners will be among those primary care providers.

“This time in our country is going to really open doors for nurses to expand their practice,” McCain says.

Given that accelerated students are highly motivated, many B.S.N. graduates will pursue graduate studies to become nurse practitioners.

“The persons who come into accelerated degree programs, by the nature of who they are, tend to be self-selecting leaders,” says DeWitty. “They are unique in many ways.”