In a recent interview, Michelle Obama said this to Oprah Winfrey about the absence of hope: “We feel the difference now. See, now, we are feeling what not having hope feels like.”

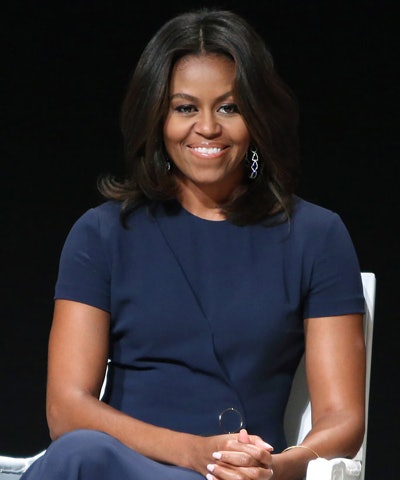

Michelle Obama

Michelle ObamaImmediately, I thought of the maíz–based Maya concepts or ethos called “men,” one of 7 maíz–based concepts I have been teaching in my classrooms for many, many years, which is a concept even more powerful than hope. However, before explaining it, Michelle Obama’s comment needs to be contextualized within the tumultuous political climate in which we are now living in this country.

Upon hearing the First Lady’s comments, the president-elect rebuffed her, claiming that she must have been referring to the past and not the future, stating: “We have tremendous hope.”

The operative word here is “we.”

On this one I do agree with the president-elect’s assessment; there is an abundance of hope from his base of support … for a return to the days of White supremacy, xenophobia, misogyny and an anti-intellectualism from a different era. Unfortunately, he and his supporters also now have power and a medieval view of the world that can help them achieve their hopes and misguided dreams. Though to be truthful, he will have dictatorial powers; it is his supporters that have the misguided dreams.

Regarding this topic, Michelle Obama also asked an important question: “What do you give your kids if you can’t give them hope.”

While the ensuing conversation has expectedly been acrimonious, her question has actually not been addressed.

As an educator, what comes to mind is the maiz-based values or ethos I learned from Yucatec Maya scholar Domingo Martinez Paredez while researching the topic of the importance of maiz to the continent many years ago. Of the 7 values, which arguably flow into each other, it is the one called “men” that is most relevant here. This concept both answers Michelle Obama’s question, and it is appropriate for these times. Martinez Paredez, who was a native Yucatec linguist and philologist, was also the author of at least 11 books (including Un Continente y Una Cultura [1960] and El Idioma Maya Hablado y El Escrito [1966] and El Hombre y el Cosmos en el Mundo Maya [1970]). Playwright Luis Valdez actually introduced us to this Maya scholar, whom he collaborated with, back in the early 1970s via a classic poem: Pensamiento Serpentino (1973), which is actually more a philosophical treatise.

There is an awesome genealogy regarding that treatise. Suffice to say that the maiz-based philosophical thoughts from that treatise wound their way into Tucson’s highly successful Mexican American Studies K-12 curriculum—the same one that was banned by the state of Arizona via SB 1070 in 2010, though not actually dismantled until 2012. Two of the principal ethos that were taught in the curriculum were: In Lak Ech (Tu Eres mi Otro Yo—you are my other me) and Panche Be (buscar la raiz en la verdad—to seek the root of the truth). While those two concepts are more readily known by more people because they were taught at MAS, it is the concept of “men” I want to explain here.

“Men,” according to Martinez Paredez, is the idea that as human beings we have the capacity to create our own reality. For example, if we enter into a situation where we are hopeless and believe we will lose, if that is our mindset, inevitably we will lose. And the inverse is true. If we believe we will succeed, if we are hopeful and believe that we will win or succeed, chances are, we will win and/or succeed.

Oftentimes warriors and athletes go into arenas with that mindset. If there is a determination that nothing will stop them from achieving victory, victory is often achieved. Any doubt and any weakening of that resolve will often result in failure.

But this concept is not limited to warfare or competition. It is simply about life itself. Specifically, the concept translates into “creer, crear y hacer.” That is, to imagine, to create and to do or to follow through. It is a formula by which to effectuate a dream … to create one’s own reality.

All of this, Martinez Paredez argues, is about a power within our psyche. A part of our will.

In one sense that is how MAS came to be in Tucson in the 1990s. It was imagined, believed in, created, shaped and then later defended. Despite the banishment in Arizona, it has now spread like wildfire across the country. People have not sat waiting around for a court decision to decide the constitutionality of the MAS ban, which is expected in early 2017. Instead MAS supporters have taken that idea, and it is now projected to be a part of all California’s major school districts and many more nationwide in the next few years.

This ethos or view of life has been applied during the battle over Ethnic Studies. It can also easily be applied to the next four years. Whatever we can imagine, we can create.

Dr. Roberto Rodriguez is an associate professor in Mexican American Studies at the University of Arizona.