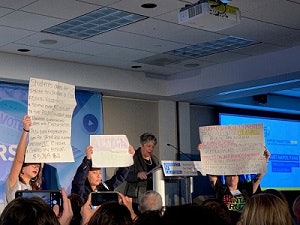

The thorny issue of free speech on campus played out in real time at the University of California (UC) National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement’s second annual #SpeechMatters Conference on Thursday when student protesters held up signs in front of the UC President Janet Napolitano as she addressed the crowd.

“The struggle inherent in respectful and lively debate is difference,” Napolitano said. “Dissent is critical. Disagreement is normal. Our differences are critical to what makes a lively, vibrant, robust economy and democracy.”

Meanwhile, students’ signs eclipsed the stage.

“Students across the UC strike to demand COLA,” one read.

“Resign now,” read another.

The students at the front of the room were a part of UCDC, a semester-long program for UC students in Washington D.C. They were protesting in solidarity with an ongoing graduate student strike at UC Santa Cruz – which has since been joined by UC Santa Barbara students – for a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) to their wages. Protesting students are demanding $1,412 more a month to be able to afford California’s skyrocketing rent prices.

During the strike, which has been going on since December, sometimes violent scuffles between strikers and campus police have increased students’ frustration, given the budget for policing versus the denied wage adjustment.

As a part of the strike, graduate students aren’t teaching their courses or submitting undergraduate grades, which risks delaying graduation for some, including UC Santa Cruz transfer student Missy Hart.

“Who are the grad students that are really suffering and the undergrad students who are suffering the most?” Hart said. “Students of color, low-income students, disabled, trans … I personally don’t have any funding past next quarter.”

What started off as a silent protest turned into sporadic disruptions throughout the conference, leading to substantive, sometimes heated exchanges about the nature of free speech.

Michelle Deutchman, executive director of the UC National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement, began by acknowledging the protesters, asking them to hold their signs on the sidelines, which they did.

“Protest is welcome so long as it doesn’t unduly interfere with the ability of the speaker to deliver the message or the ability of the audience to be able to receive the speaker’s message,” she said.

The event mostly continued unimpeded. However, when students disrupted, small arguments flared up between protesters, event organizers and audience members about whether the speakers’ right to speech outweighed the protesters’, whether the conference was a private space and to what extent it mattered.

“Considering that the event is about free speech, we’re demonstrating that … ,” began UC Santa Cruz Senior Jazleen Jacobo before Deutchman asked that they use other avenues for speech at the conference, like Q&A segments, which they later did.

With the ebb and flow of these conversations as a backdrop, conference panels delved into the intricacies of encouraging students’ civic engagement and handling campus conflict.

In a panel discussion on the line between campus protest and unlawful disruption, University of California Student Association President Varsha Sarveshwar, a UC Berkeley senior, defended students who cross that line, shutting down speech they find hateful.

She finds that there’s sometimes “condescension” from administrators, who think students don’t understand the First Amendment or the difference between speech and action, but “if you are from a marginalized community, words are incredibly powerful when they’re hate speech,” she added. “They have a huge impact on your ability to even just be a student.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison chief of police Kristen Roman described how she plans for events that may draw protest, creating a day-of-event decision-making team to take the pulse of what’s happening. And when mistakes in campus policing happen at other universities, she has a team that reviews them to analyze how their campus can do differently.

Campus police’s role is “to facilitate the educational experience of our students,” she said.

Student affairs staff also have an important role to play in fostering student expression, noted Sandra Rodriguez, director of engagement at the University of Nevada, Reno. Marginalized communities pay a “higher price” for free speech, she said, and people in positions like hers can “can challenge our students to use protesting as a platform for teaching and learning.”

Another panel explored what happens when hate crimes and speech call for legal measures, delving into the case Dumpson v. Anglin, in which Taylor Dumpson, the first African American student body president at American University, sued The Daily Stormer, a neo-Nazi website, for targeting her online, after nooses were hung on the school’s campus after her election.

Nadia Aziz, interim co-director and policy counsel at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, represented Dumpson. She told the crowd that the $700,000 settlement reached was a model for “restorative justice,” calling for a mandated apology, anti-hate counseling, anti-hate advocacy, community service and more.

As far as she knows, it was the first case to suggest that racist online activity affected someone’s day-to-day life, a “very important” precedent in this digital age. Her organization now hosts trainings on college campuses about how to identify hate crimes.

White supremacists aren’t “men in white robes” anymore, she said. “Instead of hiding behind hoods, they hide behind computer screens.”

Sara Weissman can be reached at [email protected].