The culture at Navajo Technical University in the deserts of New Mexico feels different from that of the College of Menominee Nation, nestled among the Great Lakes in Wisconsin, or from Haskell Indian Nations University, located on the Great Plains in eastern Kansas, where Dr. Daniel Wildcat is a professor.

The reason for this, Wildcat says, is attributed to the power of place.

Dr. Daniel Wildcat

Dr. Daniel Wildcat

“Our cultures and our identities emerge as unique people of the desert or unique peoples of the forest or unique people of the coastal waters,” he continues. “So the topics those schools would talk about would all be relevant to that place. I think that is one of the beautiful things about tribal colleges and universities (TCUs).”

It’s also something Wildcat believes mainstream institutions could learn from TCUs. An intimate connection to one’s place, he says, is precisely the mindset needed for fighting climate change.

A Yuchi member of the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma, Wildcat has been a sociology professor in Haskell’s School of American Indian Studies for about three decades now, but his influence has since echoed to a national scale.

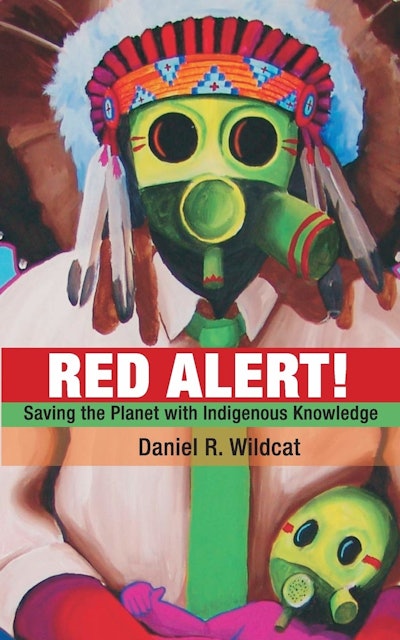

He’s been a major force in forming The Indigenous People’s Climate Change Working Group, a nationwide tribal college-centered network that’s addressing climate change issues. And he’s authored several books, the most recent one titled, Red Alert: Saving the Planet with Indigenous Knowledge.

“The most difficult changes required [to fight climate change] are not those of a physical, material, or technological character, but changes in worldviews,” he argues in Red Alert. “... In this respect, what humankind actually requires is a climate change — a cultural climate change, a change in our thinking and actions.”

He proposes a way of thinking that he likes to call “indigenuity,” a portmanteau of the phrase “indigenous ingenuity.” It involves adopting traditional, indigenous ways of thinking to solve problems caused largely by the Western world, he says. It’s a concept he drives home to his students at Haskell.

However, he acknowledges that such a cultural mind shift is no small ordeal. After all, most of his students arrive at Haskell having been influenced by the former worldview rather than the latter. And if there’s one thing he’s learned from teaching at a TCU all these years, it’s that lecturing about indigenous worldviews isn’t enough. His solution: embody what you teach.

It was one of the first lessons learned when he joined the faculty at Haskell. Having attended traditional, mainstream universities for his undergraduate and graduate degrees, Wildcat says he “was grooming himself to become a very formal kind of lecturer” or what he calls “a sage on the stage.”

“But when I got to Haskell, I realized that many of these students were the first generation in their family to go to college. If I walked in the room and just started talking, they’d just kind of look at me, like, ‘Who does this guy think he is?’”

He realized “the sage on the stage” approach wasn’t going to work there. As one Alaska Native woman told him at a climate conference, “We don't care about what you know, until we know you care.”

“That hit me like a thunderbolt,” says Wildcat. “If you're around indigenous people, what you learn is that the knowing is in the doing. … If I had remained in a majority mainstream institution, I don't think I would have really grown as a teacher the way I have at Haskell.”

Embodying one's words is another lesson mainstream institutions could potentially learn from TCUs, he says, particularly when it comes to the latest trend: land acknowledgements, which have become increasingly popular at institutions nationwide.

“If your institution is going to adopt a land acknowledgement, then you better embody those words,” he says. “I don't want land acknowledgments to become another chapter box activity. … If you're going to do an acknowledgement to that land, then that means you've got some responsibilities.”

He continues: “I really believe, if we're going to successfully address climate change, some of the most important voices to listen to on the planet today are those of indigenous people who understand and see themselves as part of the natural world. They might really have some wisdom to how we can live not just more sustainably, but more richly.”

This article originally appeared in the November 11, 2021 edition of Diverse. Read it here.