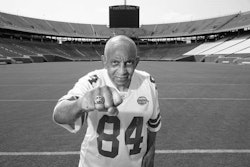

NCAA president Mark Emmert has an opportunity to lead the way on diversity.

NCAA president Mark Emmert has an opportunity to lead the way on diversity.

In the wake of the debacle surrounding the mishandling of the University of Miami investigation, much of the attention has centered on whether the NCAA and President Mark Emmert should be held to the same “institutional lack of control” standard for which schools get penalized and head coaches often get fired, due to actions often beyond their knowledge. Some have argued that for them to do anything less would represent the height of hypocrisy.

That same logic could apply to the ongoing effort to achieve meaningful diversity at all levels of college sports and especially among their governing organizations.

Take for instance the deplorable record of appointing minorities to athletic director and head football coaching positions. This year only two African-Americans — Darrell Hazell at Purdue and Willie Taggart at South Florida — were hired at major Division I level schools. And with the exception of Warde Manuel at the University of Connecticut, no new African-American athletic directors have been recently hired.

And when you look further up the leadership ranks in college athletics, what really jumps out is that, except for the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association, which represents small HBCUs, there are no women conference commissioners in the nation.

Opportunities to fill vacancies are very hard to come by at the upper levels in athletics. In most instances, those who have these positions, which are considered to be among the most enviable roles in sports, tend to hold on to them for extended periods of time. But every now and then, a windfall of an opportunity to make an emphatic statement on diversity presents itself. Such is the case that now exists at the NCAA.

No one doubts that Emmert is committed to diversity. When at the University of Washington, he simultaneously employed a Black head football coach and basketball coaches. At the NCAA, he has surrounded himself with a cadre of African-American professionals. But he would be the first to agree that the road to meaningful diversity is always under construction.

He would also agree that making appointments of African-Americans to traditional positions of leadership is where we need to be as a society.

NCAA member institutions are not compelled to follow the example set by the NCAA. But as Emmert told Diverse in the May 24 issue of the magazine, “It is a classic leadership-servant model of running an organization where you have to provide leadership on key issues and help them find solutions to the problems out there … but if the membership doesn’t want to go in some direction, you don’t go in that direction.” They can accept or reject whatever is occurring in the executive suites in Indianapolis.

But by seizing this opportunity, Emmert and the NCAA can assert the moral credibility and have the freedom of speech without reservation to urge its members to “do as I say, but more importantly, do as I do.”