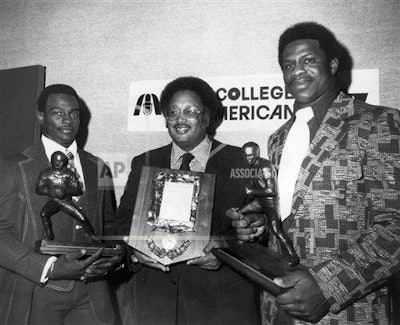

Longtime football coach and athletic director Marino Casem, flanked by former players Walter Payton (left) and Gary Johnson, says “the better well-rounded individual is a well-rounded athlete.”

Longtime football coach and athletic director Marino Casem, flanked by former players Walter Payton (left) and Gary Johnson, says “the better well-rounded individual is a well-rounded athlete.”Following Jesse Owens’ spectacular record-breaking four-gold-medal performance at the 1936 Olympics and Joe Louis’s capture of the heavyweight boxing title in 1937, a number of African-American coaches and journalists argued that African-American colleges should increase their financial support of athletics in hopes of producing more athletes who demonstrated the ability of the race.

Typical of those calls were sentiments of James D. Parks, a respected track coach at Lincoln (Pa.) University, who criticized the fact that Black colleges had failed to ever produce an Olympian. He acknowledged the financial restraints of the schools, but decried their lack of tracks and track coaches. Parks concluded that Black colleges “do not seem to realize that the development of even a single Owens or (Ralph) Metcalfe would bring more national and international renown to their institutions than a thousand of their so-called football classics (they( play among themselves.” Parks believed that by training champion athletes, Blacks earned a patriotic reputation and that their failure to do so suggested that African-Americans were unable to produce cable patriotic men.

The call for Black athletes as a form of racial advancement would be issued in various ways throughout the remaining three decades of Jim Crow, as athletes like Jackie Robinson, Althea Gibson, Bill Russell, and Arthur Ashe staked claims as the best in their sports.

But then, as now, the emphasis on athletics as a strategy for racial advancement was controversial. A number of educators and school administrators in the Black community criticized the strategy because it challenged their belief that cultivating the character of the race was the first necessity for Black advancement. In the wake of the failure of Reconstruction, African-American intellectuals from the National Council of Negro Women to Booker T. Washington argued that instilling the value of hard work, morality and character in African Americans, in addition to liberal arts and manual skills, would propel the race to equality.

This traditional African-American uplift belief clashed with an emphasis on athletics as an advancement strategy.

In the late 1930s, this conflict dominated the annual meetings of the mid-Atlantic-based Colored Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA). From its founding in 1912 through the 1970s, the CIAA was the largest sports association of African-American colleges, and Black college administrators, coaches, journalists and public intellectuals regularly attended its annual December meeting.

Speaking at the 1937 conference, Arthur Howe, the president of Hampton Institute, explained to an audience that “training students for participation in professional sports is not a matter of education.” Their contributions and earning potential, he argued, would be temporary, lasting only as long as their athletic careers.

“Any education of worth must be a preparation for life and not the first half of it.” Howe also challenged a popular argument that the physical training that made men successful on the field also led to their success in other endeavors; “experience through the years,” he noted “indicates that college athletes are no better and no worse morally than any other group of undergraduates.” As such, he recommended that athletics continued to be administered by “men who appreciate the main purpose of educational institutions and who knew how to conduct athletics without harmful over-emphasis” of virility over character. His opinion was shared by several other administrators, who followed with speeches that also questioned athletics as an advancement strategy.

Administrators like Howe applauded the race pride stirred by athletic accomplishments, but declared that virility as indicated by athletics was not indicative of the character traits that earned men, especially African-Americans, recognition as respectable citizens. His response iterated the familiar uplift critique that if African-Americans expected their institutions and accomplishments to be recognized as respectable, then they must demonstrate the moral character that many racist suggested that Blacks lacked.

Sailes agrees that there is no conclusive evidence that suggests participation in athletics builds character. “There could be (a correlation),” he says. “No doubt, moral character can be learned through sport participation. When student athletes are surveyed, they indicate that they learn teamwork, time management, sacrifice, hard work, goal setting and a host of other skills and characteristics. However, we sport sociologists also know that sport is a venue where whatever character exists in the individual will come out in sport as well.”

Marino Casem, often heralded as “the Godfather” of HBCU sports, is a long-serving and highly respected former football coach and athletic director at Alabama State, Alcorn State and Southern Universities between 1963-1999. He says the best students are neither purely athletes nor purely scholars, and that it is the job of the institution and the athletics director to foster both talents to create a more well-rounded individual. The scholar-athlete, he says will be more productive and better-prepared to face society than students who focus on only one or the other.

To him, the best men are those who have mastered both the lessons of sport and of academia. “To be an athlete only is too crude, too vulgar. To be a scholar only is to be too soft,” he says, paraphrasing Plato. “The ideal person is a man of action and a man of thought. I always held that as a principle that I followed. The better scholar, the better well-rounded individual is a well-rounded athlete. I believe that a person that will be more successful in life is a scholar-athlete.”

Despite the concerns of Howe and other educators, the belief that athletic accomplishments improved race relations ultimately prevailed in the late-1930s, because Black sports enthusiasts argued that athletic achievements had a history of fostering integration, the perceived dominant solution to Black inequality. Several advocates made that argument at CIAA conferences to counter the opposition of educators.

With integration, contestations of the belief that athletic achievement furthered racial advancement in society were largely suppressed in the African-American community. By 1960, a quarter of all professional baseball, basketball and football players were African-American and in college sports, African-Americans routinely starred on championship football and basketball teams. By then, several African-American periodicals routinely praised athletes for their contribution to the struggle for equality. In 1963, Ebony magazine even declared that athletes had a more significant influence on integration than Martin Luther King Jr.

While few Blacks today openly articulate the belief that athletic victories advance African-Americans as a group, more of them are increasingly suggesting that the lack of competitiveness of many HBCUs in sports is a detriment in the continuing struggle for Blacks’ respectability.

Still, HBCU leaders were conflicted about the role of athletics in college sports. Should athletes be positioned to advance the institutions? Should athletes be second to an academic focus? To Casem, the answer is balance, that both should co-exist without damaging the other.

“Athletics is the window through which the world views your institution. The greater the image of the athletics at that institution, the better the institution is,” he says.

Autumn Arnett contributed to this article.