Grambling State was the latest of the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU) to uneasily bare its empty wallet on our public streets the last few weeks. The storied Northern Louisiana HBCU’s financial troubles came to our national attention when its football players staged a nearly weeklong boycott. The firing of head coach Doug Williams, the school’s rundown facilities and long bus trips prompted the student-athletes to boycott practices and the October 20 game at Jackson State. They returned to practice last week and played on Saturday, but the underlying financial issues remain.

“The financial situation at Grambling is severe,” said University of Louisiana System President Sandra Woodley.

Last week, Grambling State President Frank G. Pogue issued a formal plea to the alumni.

“Grambling, when compared to other University of Louisiana System (ULS) schools, is closest to declaring financial exigency,” he wrote.

Over the past six years, the university’s state appropriation has been “drastically” reduced from $31.6 million to $13.8 million, according to the president. Since 2008, tuition and fees have risen 61 percent, while 60 percent of Grambling’s parents do not qualify for education loans, all in the midst of a slow economy and “excessive unemployment.” And these financial hurdles have not stopped Louisiana from mandating higher standards for college admissions and better performance on student retention and graduation rates.

“Despite the current budget shortfall and the anticipation of additional cuts, Grambling State University continues its commitment to educate our students and provide them with state-of-the-art technology and resources,” Pogue pledged.

The Great Recession has wreaked havoc on America, particularly Black America, and particularly HBCUs. Some analysts have suggested that the Great Recession produced the greatest loss of Black wealth in American history, devastating the ability of African-Americans to support their HBCUs.

Meanwhile, Republican-dominated state governments have been hacking at the budgets of HBCUs, while demanding for them to run more efficiently. The Grambling heartbreak is the heartbreak of dozens of other public HBCUs from Texas over to Florida and up to Pennsylvania.

HBCUs are bleeding. All over America, their enemies are watching them bleed, waiting for them to finally die. And whether they die will be up to you and me.

From their founding in the 19th and early 20th centuries, HBCUs have been ridiculed as deficient, defective and derelict — just like Black communities, Black churches, Black institutions, Black business, Black lives, Black minds and Black people. Everything associated with Black people has been demeaned — even by Black people.

We generalize individual Black negativity and individualize White negativity. In other words, when people face problems at historically White colleges and universities (HWCUs), they usually do not generalize and call their institution problematic — they certainly do not attack and question the need for HWCUs. But when something goes wrong at HBCUs, people tend to blame the HBCU brand. I do not know how many times I have heard people tell me what is wrong with HBCUs.

Despite these vicious, anti-Black, racist, ignorant critiques swirling in our discourse, students still choose HBCUs over Harvard, Stanford and Columbia every year. But people still question their viability. Students (and faculty) still transfer every year from unwelcoming HWCUs to find sanctuary at HBCUs. But people still question their utility. Black students still graduate at higher rates at HBCUs than at HWCUs. But people still disgrace their quality. HBCUs are still transforming people like me, who entered FAMU lacking academic confidence, searching for my future and straining for a genuine sense of self. But people still question the power of HBCUs.

As long as there are African-Americans, HBCUs are needed, are viable, are useful, are sites of empowerment. As long as there are African-Americans, there will be HBCUs. The only question is: How will they live? And how they live will forever be determined by how we give.

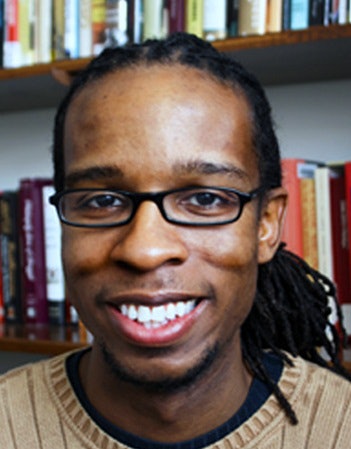

Dr. Ibram X. Kendi (formerly Ibram H. Rogers) is an assistant professor of Africana studies at the University at Albany — SUNY. He is the author of The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstitution of Higher Education, 1965-1972. Follow on Twitter @DrIbram