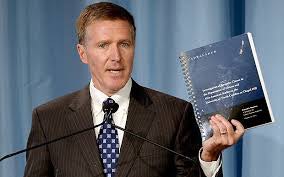

A report by former U.S. Justice Department official Kenneth Wainstein indicates that the bogus classes at the University of North Carolina ended in 2011.

A report by former U.S. Justice Department official Kenneth Wainstein indicates that the bogus classes at the University of North Carolina ended in 2011.

The latest investigation found that university leaders, faculty members and staff missed or just ignored red flags that could’ve stopped the problem years earlier. More than 3,100 students ― about half of them athletes ― benefited from sham classes and artificially high grades in the formerly named African and Afro-American Studies department (AFAM) in Chapel Hill.

A report by former U.S. Justice Department official Kenneth Wainstein indicates that the bogus classes ended in 2011. The university has since overhauled the department and implemented new policies, but it must wait to find out whether the damaging new details lead to more problems with the agency that accredits the school. The NCAA, which has reopened its investigation into academic misconduct, could also have concerns of lack of institutional control.

“Bad actions of a relatively few number of people were definitely compounded by inaction and the lack of really appropriate checks and balances,” Chancellor Carol Folt said last week. “And it was together that really allowed this to persist for such a length of time.”

The issues outlined in the report were jarring, including the clear involvement of athletic counselors who steered athletes into those bogus classes. From 1993 to 2011, those classes required no attendance and required only a research paper that received A’s and B’s without regard for quality, a cursory review often performed by an office secretary who also signed the chairman’s name to grade rolls.

Those two people ― retired administrator Deborah Crowder and former chairman Julius Nyang’oro ― were at the center of the scheme. But Wainstein’s report also notes school officials failed to act on their suspicions or specific concerns that came to their attention. It all added up to a series of missed chances to stop the fraud and instead allowed it to escalate.

Accreditation questions are now facing the university.

The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools’ Commission on Colleges had placed the campus on its watch list until this summer and required the school to allow students who took a bogus course to take another for free. The commission will send the school a letter in the next few days asking administrators to demonstrate they are still in compliance with standards required for the seal of approval, commission president Belle Wheelan said.

“What we would do is ask them is, this is bigger than you thought it was, what are you going to do now? It’s a mess,” Wheelan said.

The school’s response will be addressed by the 77-member board at its meeting in December, she said.

“We are interested in more than anything in making sure that the students don’t run into problems trying to explain any degrees that they have after the fact as a result of this,” Wheelan said.

The agency’s core requirements for accrediting a degree-granting university include clear control over “all aspects of its educational program,” including athletics. And the issue of institutional control could impact the NCAA probe, raise questions about what coaches knew and ultimately lead to possible wins and championships being vacated.

“If we go back with the NCAA in our joint review, and … if we’ve identified that we have played students who were ineligible, then obviously we would have to vacate wins at that time,” UNC athletic director Bubba Cunningham said. “But as long as the courses and the credits and everything count to the accrediting agency, we’re very comfortable with our certification process ― that our students were eligible to compete when they competed.”

The university’s fate lies in someone else’s hands now after a hands-off approach by administrators and autonomy for department chairs.

The AFAM department escaped external reviews required every five years because it lacked a graduate program. Nyang’oro was also exempt from peer reviews for tenured faculty because he was a department chairman.

Folt said she believed the school would’ve caught the fraud sooner if not for those since-removed exemptions.

The report points out there also were other chances to stop it.

Folt is holding everyone accountable.

“It really isn’t something that you could look at as only one thing,” the chancellor said. “It had the combination, and that’s why we have to make sure we can’t be complacent about it. We have to accept full responsibility for it.”