Jonathan Alger, now president of James Madison University, helped establish the RFS program during his time as senior vice president and general counsel at Rutgers.

Jonathan Alger, now president of James Madison University, helped establish the RFS program during his time as senior vice president and general counsel at Rutgers.

“There’s a lot more freedom,” Martinez says of his experience attending a high-level psychology class on the New Brunswick campus of Rutgers University. “Many students had their laptops out and taking notes. But in high school you can’t do that. There’s a lot more rules in high school.”

Martinez adds, “In college it’s like the teachers let you do whatever you want. It’s your problem if you don’t take notes.”

Martinez’s college mentor, Katherine Finer, who graduated from Rutgers this spring, says by bringing Martinez to her psychology class, she was able to relate the message: “This is what needs to be done to get here.”

Martinez — a freshman at the Health Sciences Technology High School in New Brunswick — is getting his college experience through a program called Rutgers Future Scholars.

Through the program, each year, 200 first-generation college students from families of lesser economic means in New Brunswick, Camden, Piscataway and Newark are selected to participate in pre-college activities beginning the summer before eighth grade. The pre-college activities include college entrance exam preparation, mentoring from Rutgers students and campus visits.

Perhaps more notably, those who complete the pre-college activities and are deemed “admissible” get free tuition to Rutgers.

“It’s a great opportunity,” Martinez says. “Rutgers is a pretty expensive school. Getting a free tuition scholarship to it is pretty amazing.”

Working together

As the United States seeks to boost the number of its young citizens with a college degree, programs such as RFS will play an increasingly important role in fostering diversity on campus, a number of higher education leaders say.

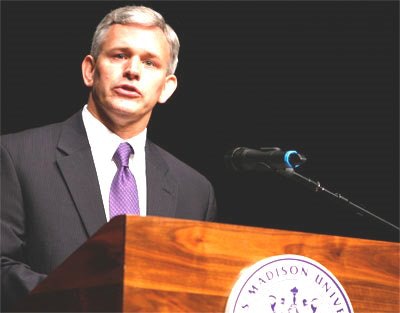

“We can’t just wait and see what K-12 delivers,” says James Madison University President Jonathan Alger, during his keynote address, “The Future of Diversity as a Compelling Interest in Higher Education,” at the annual meeting of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education in March. Alger helped establish the RFS program during his time as senior vice president and general counsel at Rutgers.

The program — which involves a partnership between Rutgers and school districts in the communities where Rutgers is based — was launched in 2008 and is funded at $1.7 million annually by the Rutgers University Foundation and corporate sponsors such as Merck and AT&T.

“We’ve got to work together across institutional lines, with employers and foundations,” says Alger. “Partnerships are important going forward.”

Alger adds that programs such as RFS will be crucial, regardless of how the U.S. Supreme Court rules in the pending Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin case, which could potentially curtail or ban the use of race in college admissions.

“So no matter what happens in the Texas case,” explains Alger, “those are the kind of programs I’d like to explore.”

RFS is just one of several programs throughout the country where institutions of higher learning are partnering with K-12 systems to provide academic, social and even financial support to prospective college students from underrepresented groups in the communities that immediately surround their campuses.

For instance, this fall in Maryland, Montgomery County Public Schools, Montgomery College and the Universities at Shady Grove are set to collaborate through a program called Achieving Collegiate Excellence and Success to create a “seamless educational pathway and support structure from high school to college completion.”

In San Diego, Calif., Compact for Success — an award-winning partnership between San Diego State University and the Sweetwater Union High School District — provides guaranteed admission for students who meet certain benchmarks, such as maintaining a 3.0 GPA or better during senior year.

Doing more

Despite the emergence of such partnerships between K-12 and higher education, educational leaders and policymakers must work together to create even more, says Deborah Santiago, co-founder and vice president for policy and research at Excelencia in Education, a D.C.-based organization that focuses on Latino issues in higher education. The organization gave CFS its Baccalaureate Level Example of Excellence award in 2007.

“We see pockets of excellence and wonderful things happening around the country,” says Santiago during a January panel hosted by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, titled “Knocking at the College Door: Projections of High School Graduates,” which predicts “rapid diversification” of prospective college students along racial and ethnic lines in the coming years.

“But we need to find way to do it more and more,” adds Santiago. “To reach our national goals, we have to accelerate.”

Like CFS, RFS is also an award-winning program. Specifically, the program won a silver award from the NASPA — Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education’s 2013 Excellence Awards.

Aramis Gutierrez, director of RFS, says a number of institutions of higher education are seeking to replicate the program, which is in line with the program’s goals.

“The idea for us is not just impacting the communities in which we are serving, but the idea is how can we create a model that can be adapted to any community,” he says.

To get accepted into the program, students must meet federal poverty guidelines, be the first in their family to attend college and attend school in Camden, Newark, New Brunswick or Piscataway.

The program seeks out seventh graders who are “not necessarily the crème” but who at least show promise, Gutierrez says.

RFS also offers professional development to teachers, explains Gutierrez, so they can “work with families to assure they understand what does it mean to have a child who is college-bound and some of the responsibilities they will now have.”

The work isn’t always easy, he says, explaining that it occasionally involves working with students who are homeless or involved in gang life.

“We have to address those issues to make sure they can focus in the classroom,” Gutierrez says. “It’s a holistic approach to supporting these young people.”

The work is evidently paying off. Future Scholars graduate from high school at a rate of 99 percent, significantly higher than the New Jersey state average of 86 percent, illustrates RFS data.

Specifically, of the 183 scholars in the inaugural cohort — referred to as the Class of 2017 — 180 were projected to graduate from high school this June, according to figures supplied by RFS. Of the 180 scholars who were expected to graduate from high school this June, 149 applied to Rutgers, 105 were accepted to Rutgers, and 89 have been admitted to Rutgers as of early May, with a few more than a dozen undecided.

The majority of scholars will be attending the School of Arts and Science. Others will be going into criminal justice, engineering, business, environmental and biological science, public administration, nursing and pharmacy, says Gutierrez.

“We have the figures to say this investment is worth it,” he says. “It’s not just about sheer numbers. But we’re talking about what impact could these young people have on the region and that goes beyond just how many graduated from high school or enrolled in Rutgers.

“We’re talking about lives transformed and that could have easily taken a vastly different path,” says Gutierrez.