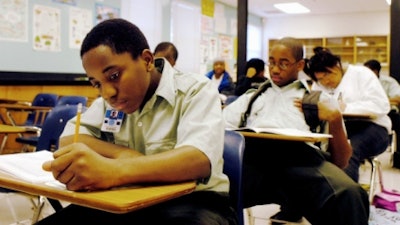

A College Board report found an increase of Black and Hispanic students who met or exceeded the SAT benchmark for college preparedness.

A College Board report found an increase of Black and Hispanic students who met or exceeded the SAT benchmark for college preparedness.The Class of 2013 had the largest percentage of minority students ever to take the SAT, but well over half of all students who took the college entrance exam failed to meet its “college and career readiness benchmark,” reveals a new report released Thursday by the College Board.

“There are those who tend to wave away the results because more diverse students are taking (the SAT),” said David Coleman, president and CEO at the College Board.

But in order for the nation to prosper, Coleman said, educators must “dramatically increase the number of students in K-12 who are prepared for college and careers.”

“We at the College Board consider this a call to action,” Coleman said of the lackluster results contained in the “2013 SAT Report on College & Career Readiness.”

“We cannot wave away the results by saying different kids are taking this exam,” he added.

The report shows that the percentage of students who scored at least 1550—a score the College Board says is associated with a B-minus or higher in college and a “high likelihood of college success”—is at 43 percent.

The figure is the same as it was for the previous two years and one percentage point lower than in 2009 and 2010 when it stood at 44 percent.

This year’s cohort is distinct in that 46 percent of the SAT takers were from minority backgrounds—the highest percentage ever and up from 40 percent in 2009.

Similarly, this year’s cohort features the largest percentage of SAT takers who hail from groups that are “typically underrepresented” in higher education at 30 percent, up from 27 percent five years ago.

On the positive side, the report found an increase in the number and percentage of African-American and Hispanic SAT takers who met or exceeded the SAT Benchmark in 2013—15.6 and 23.5 percent, respectively, versus 14.8 and 22.8 percent, respectively, in 2012.

Despite the gains, gaps remain in the level of college preparation by race and ethnicity, the report states.

“While gains in SAT participation by underrepresented minority students are encouraging, there continue to be striking differences in academic preparation among these groups that directly impact college readiness,” the report states. “To have any hope of achieving breakthrough increases in the number of our nation’s students who are prepared for college and careers, we must address the challenges these students face.”

More specifically, the report notes how White and Asian students were more likely to have taken AP and Honors courses, as well as a “core curriculum,” which the report notes is defined as four or more years of English, three or more years of mathematics, three or more years of natural science, and three or more years of social science and history.

“Nowhere is there more of a need to expand access to more rigorous coursework than among low-income and minority students,” said Cyndie Schmeiser, Chief of Assessment at the College Board.

Jennifer Engle, vice president for policy and research at the Institute for Higher Education Policy, or IHEP, said colleges and universities also have an obligation to help ensure the success of the students they admit. Among other things, she said, colleges must embrace “adaptive learning” and other methods and strategies that have proved successful with students who arrive on campus in need of remediation.

“We know they’re going to college without the kind of experience that sets them up best to be successful,” Engle said. “So there’s some onus on the college for having admitted the students. How can colleges make good on the contract that is implied by admitting and enrolling students and taking tuition dollars?”