In the Fairfield Community School District in Iowa, an eighth-grade social studies teacher quit his job after he couldn’t get the superintendent to clarify whether a new education law allowed teachers to say that slavery was wrong.

In Florida, the state board of education adopted social studies standards that ignited an uproar by calling for students to be taught about “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

The “Freedom on the Move" database, maintained at Cornell University in partnership with several universities, is a free and open archive of “runaway slave” ads placed in newspapers in the 1700s and 1800s.

The “Freedom on the Move" database, maintained at Cornell University in partnership with several universities, is a free and open archive of “runaway slave” ads placed in newspapers in the 1700s and 1800s.

Typically led by Republican-controlled legislatures seeking to reshape American education, such measures are ostensibly taken to ensure that American history is “taught accurately,” as Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, stated when he signed a bill known as HB 1084 into law.

As a former middle school teacher, journalist, and amateur historian, I wholeheartedly agree that accuracy is paramount when it comes to teaching school children about slavery and the extent to which systemic racism was or is endemic in American society.

This is why I’m so enamored with a database called “Freedom on the Move.”

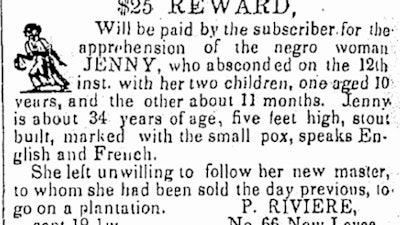

The database — maintained at Cornell University in partnership with several universities, including Howard University — is a free and open archive of “runaway slave” ads placed in newspapers in the 1700s and 1800s. The collection currently consists of more than 32,000 ads.

A portal on the website lists specific ways that K-12 educators can use the database to develop classroom lessons.

People can say a lot of things about the Freedom on the Move database. But people cannot say that it’s inaccurate or that it represents some sort of “woke” ideology — both common criticisms of contemporary public education among the political right. The database can be taken as true because it simply compiles the unedited words of the group that represents the second most authoritative source on American slavery there ever could be: the slave “owners” and “masters” themselves. But the ads also ended up telling an important story about the Black struggle for freedom.

As educator Heather Ingram noted in a video located in the website’s portal for K-12 educators, even though the ads were meant to help enslavers recapture their “property,” the ads ended up preserving the stories of enslaved people. They also serve as tangible evidence of their repudiation of captivity.

The “Freedom on the Move" database collection currently consists of more than 32,000 ads.

The “Freedom on the Move" database collection currently consists of more than 32,000 ads.

In my own studies, I have found the database of ads to be a rich repository of easily accessible digitized relics that illuminate different dimensions of U.S. slavery. For instance, as a student at the Fashion Institute of Technology, where I am currently taking an online course about athletic shoe design, I recently used the database to see how many fugitive slaves were shoemakers. I wanted to better understand the extent to which enslaved people needed footwear to foment and facilitate successful escapes.

So, I did a simple search for “shoemaker.” One of the first results that came up was a May 21, 1822, ad that enslaver Joseph Cole placed in the Charleston Courier. In the ad, Cole offered a $10 reward for “a Negro Fellow, named Sampson, a shoemaker by trade.”

The ad describes Sampson as being about 5’7” or 5’8” and states “he is an African, and bears his country marks.” It states further that he “walks lame in consequence of the loss of his toes by frost.”

Students could use this ad to explore so many different issues and questions. For instance, how was it that Sampson was a shoemaker, yet lost his toes due to frostbite? Did he become a shoemaker before or after he suffered this loss? Had his toes become frostbitten during a prior escape?

For insight into the $10 reward, students could use an inflation calculator to see how much $10 would be in today’s money. The answer is a little more than $260. Or students could research what $10 could have bought in 1822. One answer is about five pairs of boots.

And what about Sampson’s “country marks”? Were they traditional African facial and body scars that indicated belonging to a certain tribe or clan? And to what “country” does the ad refer?

The database offers an abundance of opportunities to study the plight of enslaved Black women. For instance, students might encounter an ad from the June 3, 1794, edition of The City Gazette in Charleston, South Carolina, offering a $6 reward for a 22-year-old, yellow-complexioned “stout,” five-foot-five “lusty wench” named Lydia. Despite the crude sounding nature of the phrase, a closer look reveals that its meaning may not quite be how it sounds. The word “lusty” means “healthy, energetic, and full of strength and power.” The word “wench” started out as a general term for a girl or woman, “and over the centuries acquired a variety of meanings, including female servant, lower-class female, and prostitute,” according to retired English professor Paul Brians’ “Common Errors in English Usage.”

Lydia may have run away from the City Gazette “subscriber,” Charles Watts, but she evidently didn’t run very far.

“She is still lurking about the city, as she was seen last Sunday morning on the Bay,” the ad states.

The ad for Lydia, as do many if not most of the other ads in the database, makes clear that free society was prohibited from rendering aid to runaway slaves.

“All persons are forbid harboring or employing her under pain of being prosecuted as the law directs,” the ad states. Lydia’s owner claimed that Lydia would be forgiven if she “returns of her own accord.”

Many enslaved women simply wanted to be with their husbands. For instance, a “negro wench named Phoebe” was thought to have run off to another plantation where she had two brothers and a husband.

The ad – taken out by Martha Bolton – offered disparate rewards for Phoebe’s return depending on if her return was brought about by a white person or a person of color. As Martha Bolton states in her ad: “If harbored by a white person, four pounds will be given; if a negro or person of color, two pounds on conviction of the offender.”

In exploring the ads found within the Freedom on the Move database, the folly of debating the extent to which racism was endemic in American society becomes abundantly clear. Slave owners paid newspapers to advertise a financial reward to entice members of the public to help them locate their runaway “fellows” like Sampson and “lusty wenches” like Lydia. And those ads warned people that they could be prosecuted if they rendered aid to fugitives.

When businessmen, the media, and the courts are all aligned around one purpose — to keep Black people in captivity — little question remains about the degree to which racial oppression in American society was endemic and systemic. A more intelligent question would be how long slavery would have lasted if newspapers and the courts didn’t agree to help slave owners out whenever their “property” ran away.