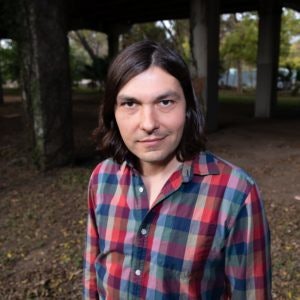

Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr. leads students in a discussion.

Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr. leads students in a discussion.

Hadzi-Antich designed the course in response to ACC’s Student Success Course mandate which are required courses that help students develop the skills associated with persistence. Hadzi-Antich felt that the humanities fit that need perfectly.

“The periphery static I heard was, 'I don’t think community college students can handle reading transformative works.' And that pissed me off,” said Hadzi-Antich, who had taught heady, classic texts to his students and seen them thrive. “Community college students are college students. They are half of American undergraduates. If they can’t handle reading source texts and transformative works, what does that say about our estimation of half the population of undergrads?”

After a two-year pilot that started in 2015, Great Questions has grown to roughly 20 classes a semester and over 100 faculty members have taught the class. So far, the numbers show the Great Questions course is achieving its intended goal: students who took Great Questions in fall 2020 had a 98% chance of persisting through to spring 2021.

As community colleges face dramatic enrollment declines across the country, some colleges are expanding their offerings to include technical and skills-based programs. Often, large companies like Google or Amazon partner with colleges for workforce training. But humanities courses are still going strong. According to a 2018 study by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, more degrees in liberal arts and humanities were awarded at community colleges than at four-year institutions. Experts say that humanities, and their integration into workforce programs, helps higher education’s mission to create more employable, well-rounded citizens in American democracy and society.

“The students become not just active collaborators in learning, but the driving force. And it’s really, really remarkable to see students initially hesitant leaving feeling full of confidence,” said Hadzi-Antich.

Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr., associate professor of government and founder of The Great Questions Project at Austin Community College.

Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr., associate professor of government and founder of The Great Questions Project at Austin Community College.

Andrew Rusnak, executive director of the Community College Humanities Association and associate professor of English at the Community College of Baltimore County, Essex, said that most employers want to hire someone who knows how to think critically, how to apply analytical skills and learn to build teams.

“Those [skills] are all the cognitive byproduct of studying the humanities,” said Rusnak.

The higher education environment used to be more hostile to the humanities, said Rusnak, and more favorable to utilitarian studies. But he has seen that change as real-world events impact the lives of students, like the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd.

“I’m seeing the incipient growth of students who seem to be taking a much stronger interest in all things human, what’s going on in the world, and how to think about it,” said Rusnak. “Specific pivotal points have all been adding up to young students expressing a desire to want to understand the world that they live in, not just in quantifiable ways but in abstract thinking.”

The humanities, said Rusnak, “underlie just about everything we do in natural sciences, social sciences, and even some work prep programs.”

“There’s a lot of community college professors doing really innovative things when it comes to the humanities, [finding] ways to integrate and understand relationships between disciplines,” said Rusnak. “Humanities professors work with non-humanities professors in other disciplines, creating an understand of how they relate to each other, teams of professors working on curriculum and pedagogy to get students to understand how the humanities work in biology or engineering.”

Hadzi-Antich has taken that multi-discipline approach and helped to create more discussion-based courses for students at ACC. He has gathered faculty from mathematics and humanities and asked them each to select core texts to read with and explore in the semester. They work together to develop pedagogy and syllabi that facilitate student-centered discussion.

Hadzi-Antich also started a nonprofit, Great Questions Foundation, whose mission statement is to reinvigorate liberal arts and humanities-based learning in general education at community colleges. He said he is motivated by the number of students who attend community colleges in America, whether for one class, for transfer, or for their associate's degree.

Students learn in a liberal art course "skills that are associated with productive, civic participation in democracy. They hear arguments they disagree with, weigh their own thoughts in light of new evidence, and engage across disciplines," he said. "If students lose that opportunity in their first and second year, they are likely to never have that opportunity. Focusing on texts that are important to us as humans is essential to thrive as a community college.”

Liann Herder can be reached at [email protected].