Several years after he began work as an associate at Munger, Tolles & Olson, a white-shoe law firm in downtown Los Angeles, Michael Waterstone decided that he wanted to make the transition to teaching, where he could also write and think broadly about social justice issues.

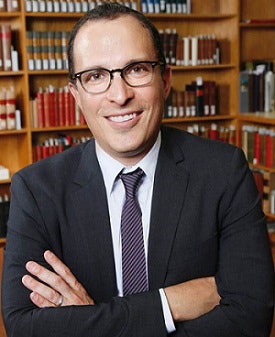

Michael Waterstone

Michael WaterstoneAlready interested in civil rights law — specifically how it relates to people with disabilities — the Harvard Law School graduate who clerked for the late judge Richard S. Arnold in Little Rock, Arkansas straight out of law school, eventually received several teaching offers before settling on a position as an assistant law professor at the University of Mississippi.

“My wife and I spent three very happy years in Oxford, Mississippi,” says Waterstone.

“Amongst other things, I taught civil rights and that was just an amazing experience teaching a civil rights course there,” he adds, noting that his tenure on the faculty at Ole Miss coincided with the retrial of Ku Klux Klan member Edgar Ray Killen.

In 2005, Killen was found guilty of orchestrating the murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in 1964.

“I was in the courthouse. I went with students and that was just a fascinating sense of history to be around,” says Waterstone.

After spending three years on the University of Mississippi law school faculty, Waterstone and his wife—who also taught in a clinical program at the law school focused on juvenile justice issues—decided to head back to Southern California to be closer to family.

Loyola Marymount University hired Waterstone as an associate professor in 2006, and he steadily rose through the administrative ranks as an associate dean for Research and Academic Centers and now the Fritz B. Burns Deans of the law school and senior vice president of the university, a post that he has held for three years.

Along the way, Waterstone has gained a national reputation as an authority on civil procedure, disability law, civil rights law and employment law.

“I’m incredibly proud of our school,” he says. “I think that legal education has an obligation to turn out graduates that look like the community that they serve.”

Waterstone says that the legal system works best when it reflects the diversity of its community and Loyola has made inclusion a central part of its overall mission.

“We strive to have students that look like the great city of Los Angeles,” says Waterstone, who has written extensively about diversity and accessibility issues for students with disabilities.

Founded in 1920, the law school requires all law students to do some pro bono work before they graduate. This mandate reflects the school’s Jesuit philosophy and outreach.

“We are committed to forming lawyers who go on to serve others,” says Waterstone. “Our legal system and our access to the justice system is broken and we want to produce lawyers who have the tools and skills to go out and in the words of St. Ignatius Loyola, ‘Set the world on fire.’”

The most visual manifestation of the school’s mission can be found in the work of the school’s clinics, where law students are “serving the most vulnerable members of our community” by providing their expertise and legal training to those who otherwise could not afford it. The school supports the Cancer Legal Resource Center, the Sports Law Institute and the Center for Juvenile Law & Policy.

“By being trained in that way while they’re still in law school, we’re creating the next generation of lawyers who go out and be advocates for social justice,” says Waterstone, adding that not all of Loyola students need to go into public interest law “but we want them to have the training and the appetite to always pay attention and be a force for good on these issues.”

When it comes to recruiting and retaining students of color, Loyola is ahead of many other schools boasting a population of about 37 percent.

“We’re never satisfied and we can do better,” says Waterstone. “But I think it’s something that we work very hard at.”

Recruiting more students of color is a shared responsibility that includes tapping into alumni networks and using current students as ambassadors for the school, he says.

Waterstone says that programs like “First to Go” – which provides academic support and engagement for first-generation college students – has been useful for students.

Waterstone spends much of his time fundraising in an effort to create more scholarships at the law school. He says that his goal is to go out and recruit the most talented students to attend the law school, regardless of their financial situation.

“In addition to providing the most scholarships that we can, the best thing we can do is put students in a position where they can pass the bar and get that important first job, because then they’re at a much better professional and financial position to start their careers.”

This article appeared in the July 12 issue of Diverse. It is one in a series of stories about law school deans.