NEW YORK— Adjoa Aboagye, 40, learned about Frederick Douglass – the former slave turned abolitionist leader – in high school. But an event at her first National Action Network convention gave her richer insight into what his legacy means today, 400 years after the first slaves were brought to America.

“It reminded me to be more nuanced about historical figures,” she said.

Aboagye attended a session at the 28th annual National Action Network convention entitled “Four Hundred Years Later: Understanding Slavery and Freedom Through the Eyes of Frederick Douglass.” The event drew a crowd of more than 300 people to the East Ballroom at the Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel on Wednesday afternoon.

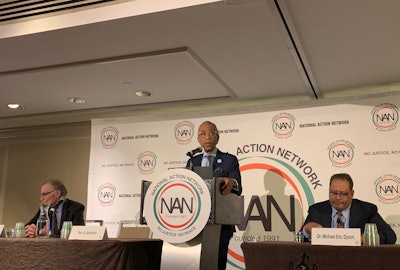

There, Rev. Al Sharpton, founder of the National Action Network, held a conversation with Yale University historian Dr. David Blight and Georgetown sociologist Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, followed by a book signing with the two authors. The discussion focused on Douglass’s reflections toward the end of his life and what those years can teach a community divided under the Trump administration.

Even in the time of Frederick Douglass, “there were always fights with different segments of the movement,” Sharpton said.

Last year, Blight published Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, a biography born out of a private archival collection in Savannah, Georgia containing ten of Douglass’s family scrapbooks.

“No one helped explain, had more to say, represented the interior psychological and exterior physical experience of slavery could do to the human being and the human body like Frederick Douglass,” Blight said.

According to Blight, most Americans only know about Douglass’s life as a young man – his escape from slavery, his fiery speeches and autobiographies. But they’re missing the last third of his life.

“The Douglass frankly almost nobody knows is the older Douglass,” he said. “But that older Douglass becomes this complicated, fascinating, interesting human being like all of us who age.”

It’s that Douglass who lived 30 years after the Civil War, confronting the complex reality of its aftermath.

Douglass lived “to see the triumph of his cause in the middle of his life …” Blight said. “He’s also going to live long enough to see that very triumph betrayed, defeated and all but erased by terror, by violence, by the Supreme Court, by the changing Republican party and by the White supremacists in the Democratic party.”

Notably, as he grew older, Douglass shifted from a radical outsider to a political insider. He received three federal appointments and lived out the end of his life in Washington, D.C. He got flack for it, Blight said.

Younger Black leaders critiqued him for his insider status, his conservatism and his second marriage to a White abolitionist.

Dyson pointed out that this is a live issue. There’s an ongoing debate over who authentically follows the legacy left by leaders like Douglass and who qualifies as “sellouts,” he said, when Douglass and other icons of the Civil Rights Movement were living, evolving people.

“Nostalgia has no history,” Dyson added. “It’s rooted in a prism of rose-colored glasses and no one really sees what was going on.”

The book, however, “renders Douglass a full-fledged human being,” he said, a complex figure trying to bridge the divide between radical abolitionists and policymakers. “He defended the young people who were now assailing him.”

Dyson noted that this tension – fighting criticism from within one’s own movement – directly impacted leaders in the room. Sharpton confronted similar critiques as a former adviser to President Barack Obama and had to “negotiate both criticism of Obama, which was legitimate, and defense of him in the face of white supremacy,” Dyson said, which wasn’t an easy task.

Rev. Al Sharpton

Rev. Al Sharpton“Ultimately, decisions that are driven by high moral conscience or deep and profound commitment to ideals will sometimes contradict the very positions that the people you love the most are going to want you to adopt.”

For Dyson, Blight’s nuanced portrayal of an aging Douglass carries a powerful message for present-day politics: Moral leadership is messy, and even beloved figures leave behind complicated legacies.

“When you look at Frederick Douglass, you have to give up on the politics of purity,” he said. “Jesus isn’t running for office. Allah is not running for state government. These are human beings compromise by their own desires … captive of their own audience and media – and yet in the midst of that creating opportunities for others by the level and dramatic intensity of their sacrifice.”