At least 36 million Americans have some college education but never completed their degree, according to a new report by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

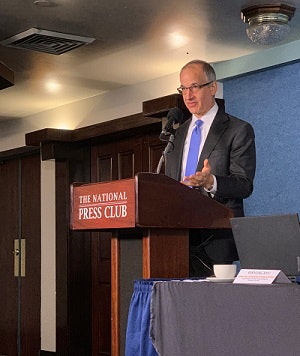

Dr. Doug Shapiro

Dr. Doug ShapiroWhile that number seems bleak, the data also tells another story, arguably a more hopeful one. The report – titled “Some College, No Degree: A 2019 Snapshot for the Nation and 50 States” – found that 3.8 million of these former students returned to school and are now working toward or have finished their degrees. The conclusion of the report is that if institutions and state lawmakers learn more about who these returnees are, they can create targeted outreach strategies and policies to help this population graduate.

At the National Press Club on Wednesday, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center held a panel discussion to explore the implications of the data.

The panel featured Dr. Mikyung Ryu, the organization’s director of research publications, Dr. Sally Johnstone, president of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, Dr. Hadass Sheffer, president of The Graduate! Network, Leanne Davis, assistant director of applied research at the Institute for Higher Education Policy and Dr. Courtney Brown, vice president of strategic impact at the Lumina Foundation.

Dr. Doug Shapiro, executive research director at the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, pointed out in his opening remarks that students who re-enroll are typically “invisible and ignored” when institutions calculate their graduation rates. They’re written off as dropouts and no longer considered a part of the equation once they leave.

“What has become abundantly clear is there are a lot of student successes among this population,” Shapiro said. “And these are successes that we should be celebrating a lot more and learning a lot more from.”

Following up on a 2014 study, the new report uses 2018 data to delve into the demographics of students returning to complete their degrees, where and when they re-enroll and specifically who makes up “potential completers,” people with two or more years of college education who show a higher likelihood of graduating when they go back to school.

Ryu presented some of the study’s key findings. The average “some college, no degree” student has a median age of 39 years old and began college in his or her early 20s. Most started their higher education at community colleges about 10 years ago and stayed less than two years. The majority re-enroll at a community college, usually an institution different from their first but in the same state.

The report also identifies 3.5 million “potential completers,” former students who already made significant headway towards their degrees before they re-enrolled. According to the data, these former students tend to be younger and make up 10 percent of returnees.

Among the success stories, people who return and complete their degrees, most earn associate degrees and certificates. Higher proportions of minority students are represented in this group compared to college graduates nationally. Black and Latinx students make up a full quarter of people who return for their bachelor’s degrees and 32 percent of those who return for associate degrees, compared to national percentages which are 16 percent and 23 percent respectively.

Brown described this data point as a “glimmer of hope,” given the obstacles minority and nontraditional students face in higher education.

“Our college system is not set up for today’s students,” she said. “Our system is set up for someone to enter the brick building at 18, paid for by their parents, and walk out and have a job for life. That’s not our reality.”

Panelists discussed the specific barriers that lead students to leave college without returning.

Sometimes, it’s the logistics of navigating a “complex” and “fragmented” system, said Sheffer. She compared the experience to a “bad marriage.”

“Very few people leave a college and say, ‘I’m never going back to that college just because I didn’t like the color of the walls,’” she said. “There are fundamental issues there.”

The bureaucracy doesn’t end when they leave, she added. Schools make it difficult for students to simply receive their credits or get their transcripts once they’ve left.

They also often lack the resources working and adult learners need, like nighttime and weekend course options.

But panelists also pointed out ways to re-engage these students, with the help of the latest available data.

Because most returnees re-enroll in a public institution in the same state as their first, higher education institutions and state policymakers now know which students are most receptive to outreach and from what institutions.

That outreach is pragmatic for colleges, Johnstone said. Schools want to increase their enrollment, and it actually costs institutions less to re-engage a former student than it does to recruit a new one.

There are schools already trying to attract former students, like Shasta College, David pointed out. The school’s Accelerated College Education program re-engages former students by creating a cohort with a consistent class schedule, which makes it easier for students to work and arrange childcare.

Meanwhile, state lawmakers can play a role, as well. Several panelists pointed to Tennessee Reconnect – a program that offers grants to returning students in the state of Tennessee. Now 43 states have degree-attainment goals that these students can help to fill.

It’s important “to see this population as an opportunity, and not just as evidence of failure of education,” Shapiro said. “It’s an opportunity for institutions to find more enrollments, it’s an opportunity for our states and for our adult citizens in this country to find success.”

Sara Weissman can be reached at [email protected].