CHICAGO — On a recent Saturday night, a crowd began forming early at The Book Cellar, cramming into one of the city’s last independent bookstores.

Jeff Donohue had planned to drop his wife Cathy off to hear Dr. Ibram X. Kendi’s talk and return two hours later to pick her up. But that was before she made the public pronouncement for all to hear.

“You need to sit down and learn something,” Cathy told her husband, who appeared agitated and slightly embarrassed by the forceful directive.

With that, Jeff begrudgingly took a seat next to his wife, unaware of how Kendi’s talk and his “book” would forever change his outlook.

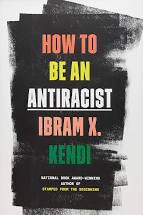

That’s the story that has been recounted across the nation as Americans grapple with How to Be an Antiracist, the 305-page New York Times bestseller that has catapulted Kendi — already a National Book Award winner, professor and founding director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University — to greater heights.

Part memoir but firmly grounded in history and current events, the reader comes to understand how Kendi’s ideas about race and racism were shaped by his years growing up in northern Virginia, his time as an undergraduate at a historically Black university in Florida, and later as a Ph.D. student in African-American studies at Temple University, the first institution in the nation to offer a Ph.D. in the discipline.

“This book is ultimately about the basic struggle we’re in, the struggle to be fully human and to see that others are fully human,” Kendi writes in the introduction to the book. “I share my own journey of being raised in the dueling racial consciousness of the Reagan-area Black middle class, then right-turning onto the ten-lane highway of anti-Black-racism — a highway mysteriously free of police and free on gas — and veering off onto the two-lane highway of anti-White racism, where gas is rare and police are everywhere, before finding and turning down the unlit dirt road of antiracism.”

An antiracist world is possible, Kendi declares, “if we focus on power instead of people, if we focus on changing policy instead of groups of people. It’s possible if we overcome our cynicism about the permanence of racism. We know how to be racist. We know how to pretend to be not racist. Now let’s know how to be antiracist.”

Kendi’s book is revealing, in that he describes his own challenges and struggles and candidly writes about his younger self as a “racist, sexist homophobe.” At the book signing and talk in Chicago, Kendi noted that racism can’t be viewed in isolation from other “isms.”

“You can’t separate the origins of racism from the origins of capitalism,” said Kendi, a former contributor to Diverse. “You can’t be an antiracist if you’re a pro-capitalist because they’re like conjoined twins.” He argues that in order to be antiracist, one should be willing to become a feminist and actively address forms of patriarchy.

For Kendi, who burst onto the national scene with Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, racism has to be treated like a metastatic cancer that requires ongoing vigilance and a steady regimen because it has now “spread to nearly every part of the body politic.”

The analogy is deeply personal for Kendi, who was diagnosed a few years ago with Stage 4 colon cancer, which brought his own mortality into closer view.

“What if we treated racism in the way we treat cancer,” writes Kendi. “What has historically been effective at combatting racism is analogous to what has been effective at combatting cancer. I am talking about the treatment methods that gave me a chance at life, that give millions of cancer fighters and survivors like me, like you, like our loved ones, a chance at life. The treatment methods that gave millions of our relatives and friends and idols who did not survive cancer a chance at a few more days, months, years of life. What if humans connected the treatment plans?”

Dr. Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, praises Kendi’s book for “challenging both mainstream and antiracist orthodoxy,” and illuminating “the foundations of racism in revolutionary new ways.”

The usefulness of the book, as DiAngelo rightly notes, is that Kendi “offers us a necessary and critical way forward,” by providing clear recommendations that can be exercised by everyone who wants to get rid of racism.

That’s the message that Jeff Donohue took away from Kendi’s talk as he waited in line to get a copy of How to Be an Antiracist signed by the author.

“I’ve got a lot of work to do,” said an emotional Donohue, who locked arms with his wife after the book signing. “I’m really glad that I stayed. I needed to hear this.”

His biggest takeaway?

“From now on, it’s not enough for me to simply say that I’m not a racist,” he said with a broad smile on his face, as Cathy Donohue shook her head in agreement. “I’ve got to do more. I’ve got to be an antiracist.”