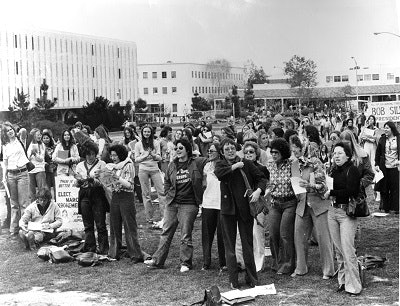

During the 1960s, social movements gained momentum across the United States in neighborhoods, cities and on college campuses, many of which focused on racial and gender rights.

San Diego State University (SDSU) was one of the many institutions at the forefront of the fight for women’s rights.

In 1969, the SDSU community advocated for the development of a women’s studies program on campus. Alongside faculty members and community members, students from SDSU’s Women’s Liberation Group formed an Ad Hoc Committee for Women’s Studies, according to the program’s website.

At the time, the program offered 11 courses. However, five years later, after faculty developed an 18-unit minor, the program became a full-fledged academic department that is now the Department of Women’s Studies housed in SDSU’s College of Arts and Letters.

“I don’t think there’s any discipline that puts the experiences of women, gender and sexuality at the very center of knowledge as opposed to a kind of add on,” says Dr. Doreen Mattingly, professor and chair of the Department of Women’s Studies at SDSU. “I think that has really caused a revolution.”

In 1983, the department created an undergraduate major in women’s studies and went on to establish a graduate program 13 years later.

Over the years, the department has also implemented a feminist science program, an LGBT studies major and minor as well as developed the Bread and Roses Center for Feminist Research and Activism center.

“For a lot of students, being in a women’s studies class allows for a lot of personal growth and change that I think leads to more opportunities, avenues and more possibilities for them,” says Mattingly.

This year, SDSU’s Department of Women’s Studies will celebrate its 50th anniversary.

“I like the fact that I’m teaching in a department that’s the first of its kind,” says Dr. Kimala Price, associate professor of women’s studies at SDSU. “Our birthday is a landmark for the entire discipline. I think that’s really cool.”

To commemorate the anniversary, SDSU will host a Gender and Social Festival in April. Art students will be integrated into the event where they will showcase various performances, films and artwork based on the overarching theme of gender and social justice.

With around 1,500 people expected, there will be more than 30 panels, speakers and sessions.

Mattingly, who has worked in the department for 25 years, says the festival can also provide an opportunity to address various gaps in women’s studies including the generational gap between young feminists and older feminists.

“I think we wanted to have a festival so that we could bring people together of different generations,” says Mattingly. “People that work on different issues, that might live and work in different communities to meet each other, hear each other and have some fun together and form the kinds of alliances that will move the next round of social and gender activism forward.”

Since its establishment, the curriculum has become more internationally driven, according to Mattingly.

For the international element, the department has developed study abroad programs. For example, this summer, a program will be offered in Buenos Aires, Argentina that focuses on feminism, queer and transgender activism in relation to the current state of violence and economic neoliberalism in the country, according to the department’s website.

The international shift has led to the development of more international courses such as “Women in Asian Societies,” “Women, Development and the Global Economy,” “History of Women and Sexuality in Modern Europe” and “Global Cultures and Women’s Lives.”

Many faculty members have tied international elements to their research including topics on the LGBT community in Muslim countries and postcolonial women’s arts.

According to Price, about half of the faculty in the department are women of color.

“That’s also reflected in the curriculum that we have developed over the years,” she says.

As someone with a background in both political science and women’s studies, Price says this department gives her the opportunity to interact with both disciplines.

“Since I’ve been in the women’s studies department, I’ve been able to do my research as well as work in the community and [engage in] policy work,” she says. “And that is being valued by the department and university, so I don’t have to choose.”

In addition to courses and programs, the department offers several scholarship and need-based financial aid opportunities for both undergraduate and graduate students. On average, the program offers around $1,000 in scholarships for students based on their GPAs, commitment to activism or for those who are first-generation students.

Mattingly says that women’s studies students are “passionate” and, as a teacher, “you get to introduce people to ideas and texts that allow them to look at the world in a fundamentally different way that gives them more space, more autonomy and more opportunities for connection.”

According to Price, many students discover the women’s department when they arrive on campus.

“It’s not until they start taking our classes and they realize, ‘Why haven’t I been exposed to this stuff before? This is really interesting,’” she says. “So, then they get hooked and they become involved in our department and we have some of the most active students on campus.”

Despite many people thinking that women studies departments are a “fad,” Price says they are here to stay.

“I think it’s a testament to a lot of the work that was done with the people who piloted this 50 years ago and the people that continue to work in this field and help it grow and expand it in many exciting and unexpected ways,” she says.

More recently, Price has found that the current political climate has “boosted” people’s interest in the department as students are looking for answers.

“They are trying to make sense of what’s going on in the world,” she says. “They might find it in some of the other departments but really women’s studies and ethnic studies, that’s what we do.”

For example, over the years, Price has taught classes focused on sexual harassment. Student interest in the topic peaked after accusations came out against film producer Harvey Weinstein and the “Me Too” movement emerged.

“Now the discussions that I’m having in my classes are even more robust,” says Price. “Because [students] are trying to make sense of what is this, why is it allowed to continue and are there laws and policies in place that can protect people from this kind of behavior.”

Mattingly says the department’s growth has been a grassroots phenomenon.

“When individual faculty or groups of faculty and students have passion and direction then they move it that way,” she adds. “So, I would like it to continue to change following the ideas of people in the department.”

This fall, the department plans to expand the feminist science studies program and establish a minor in science, technology and society studies.

According to Mattingly, although education can’t cure everything, “a lot of things can be aided by a feminist education.”

This article originally appeared in the March 19, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.