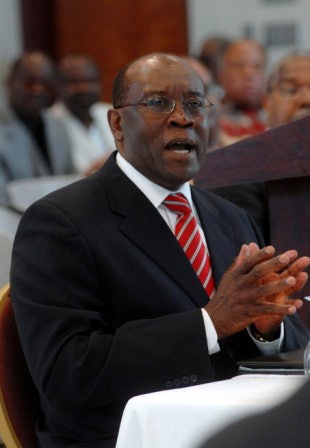

Dr. Andrew Hugine has been successful at reversing Alabama A&M’s financial losses.

Dr. Andrew Hugine has been successful at reversing Alabama A&M’s financial losses.When Dr. Andrew Hugine left his post as president of South Carolina State University to become president of Alabama A&M University in 2009, both institutions were prototypes of historically Black universities in crisis.

But in August 2012, nearly a year before his contract was scheduled to expire, Hugine received a hearty nod of approval from AAMU’s trustees when they voted to extend his contract to 2017, maintaining his $230,000 salary but adding performance incentives.

So Diverse examined how this turnaround occurred amid the toughest times in recent history for HBCUs, particularly, the latest national setback from the federal government’s tougher standards for Parent Plus Loans, which resulted in declining enrollment and a $150 million loss to HBCUs overall.

“When I arrived in 2009, the university was on probation with SACS [Southern Association of Colleges and Schools] … and that probation had to do with the financial health and management of the university,” Hugine says, listing a few of the main issues he confronted: a $10 million loss in state funding, five different presidents—either permanent or interim over a six-year period–$100 million of deferred maintenance and overstaffing.

Hugine assessed this environment and immediately tapped into the city’s resources—and needs. Alabama A&M is located in the high-tech city of Huntsville, Ala., home to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and the U.S. Space and Rocket Center.

He learned that the high schools needed a new stadium. After negotiations with city and school district officials, a partnership resulted in A&M’s stadium being upgraded for use by the high schools and the university’s football team.

By making comparisons to other similar land-grant institutions, Hugine’s administration concluded that A&M was overstaffed by about 200 employees. In addition to furloughs and layoffs, they offered early retirement packages to employees to reduce staff, outsourced the facilities management and introduced a program that allows students who take more than the minimum required credit hours to forgo paying additional tuition for the additional courses. The administration also merged five schools into four colleges and added new academic programs.

“We looked at everything in order to right the financial picture,” says Hugine. “We had to do something. We had no choice, and it was painful.”

Through these measures, Hugine ushered the university out of its probationary status with SACS and reversed the financial losses. Enrollment, which plummeted 12 percent in Hugine’s first year, was at 4,950 last year. This year, Hugine says enrollment is 5,008, showing a modest upward trend. His goal is to add 1,500 more students in coming years.

Even some of Hugine’s critics acknowledge his accomplishments. Trustee Richard Reynolds, who is quick to say “I am not a yes-man to the president and his administration,” is also quick to commend Hugine for bringing much-needed financial and administrative stability to the university.

“There has been a turnaround,” he says. “The university was at a pretty low point when [Hugine] took over; there was a recession, and we are a government town. Federal and state funding was cut. He had a double whammy.”

“He’s not perfect, and we’ve had our disagreements,” Reynolds adds, “but I give credit where credit is due.”

Student Government Association President Keith Williams, a senior mechanical engineering major, says that, after some rough spots in recent years, students seem optimistic about Hugine’s leadership, especially in light of his tuition initiative that has financially benefited students and their families.

Board of trustees chairman Odysseus Lanier says one reason for Hugine’s success has been board support.

“Alabama A&M had a 30-year history of institutional dysfunction,” he says. “One of the things that was important to me was having the board put in place a model of allowing a president to be president; … we don’t make personnel decisions for him; … we don’t call him every 15 minutes. We looked at ways that we could help him be successful rather than looking for things that he was doing wrong. It was a very difficult process of trying to change the governance culture.”

Most important, says Lanier, is the bottom line.

“We had a 2009 audit that showed a $9 million negative net asset balance—that means we had no cash, no resources,” he explains. “In the fiscal year 2012 audited financial statement, because of decisions [Hugine] made and we supported, we had a $3.79 million positive asset balance—that’s a $13 million swing in three years. Amazing.”