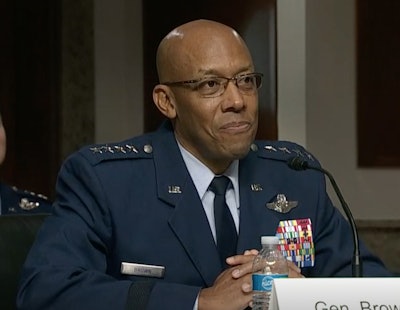

On June 9th, the United States Senate unanimously confirmed Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. to become Air Force chief of staff, making him the first African American to lead a branch of the U.S. military.

Brown’s confirmation came shortly after he made a video in which he discussed what he was thinking in the wake of George Floyd’s death. “I’m thinking about a history of racial issues and my own experiences that didn’t always sing of liberty and equality,” said Brown, who achieved the rank of four-star general in 2018. “I’m thinking about living in two worlds, each with their own perspective and views.”

Secretary of the Air Force Barbara M. Barrett administers the oath of office to incoming Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown, Jr.

Secretary of the Air Force Barbara M. Barrett administers the oath of office to incoming Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown, Jr.While an examination of Brown’s career shows many achievements and outstanding leadership, in the video he was honest about challenges he faced. At times he was the only African American in his squadron, and, when he became a senior officer, he was often the only African American in the room.

He noted that he rarely had a mentor who “looked like me,” but appreciated the sound advice he received even though “most of my mentors could not relate to my experiences as an African American.”

A central element in Brown’s ascension through the ranks was education, says Dr. David Vacchi, who retired from the Army at the rank of lieutenant colonel and is a consultant on veteran services and leadership development. A college degree is a requirement for earning a commission as an officer.

“[Gen. Brown’s] college degrees and his Air Force leadership training have honed his skills in critical thinking, oral presentation, communication skills and effective writing,” says Vacchi.

“The military develops leaders by providing education and operational experience. In other words: go to school, learn your business and then put that education into practice,” says Lt. Gen. Gary H. Cheek (U.S. Army, retired), director of the Bass Military Scholars Program at Vanderbilt University and a friend of Brown’s.

“It is a continuous process where leaders attend schools at different points in their careers to ensure their intellectual abilities rise with greater responsibility,” he adds. “This includes both military and civilian education, as has been the case for Gen. Brown.”

Gen. Brown’s education

Brown attended Texas Tech University, where he earned a B.S. in civil engineering in 1984. While there, he participated in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), which provided scholarship money. He received his first commission in 1985.

More than 1,100 colleges and universities currently offer Air Force ROTC. On its website, the Air Force ROTC notes that the program offers leadership opportunities and professional development. Those accepted into ROTC must meet academic standards, fitness requirements and medical requirements. Pilots must fulfill a 10-year active-duty requirement.

To advance past the rank of captain, which Brown reached in 1989, requires an advanced degree. Brown enrolled in Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, earning a Master of Aeronautical Science in 1994. He studied at the Worldwide Campus, which means his courses took place on the bases to which he was assigned. Today, many of those courses are

“We’re the part of Embry-Riddle that really supports the military,” says Dr. John Watret, chancellor of Embry-Riddle’s Worldwide Campus. “The key to our degree programs is that service personnel can start a degree program at any of the bases. As he or she transitions and grows and even moves to another base, they can seamlessly continue with their education.”

Watret says, in addition to technical courses, Brown’s master’s degree program would have included material on leadership, management and other aspects of the aviation industry. Watret notes that Brown’s knowledge of aviation aids him in understanding aspects of military defense, such as space exploration and unmanned vehicles.

Embry-Riddle’s data shows the university’s greatest diversity comes among its Worldwide Campus and military-connected students. In the fall of 2019, just 2.6% of graduate students on the Daytona Beach, Florida campus were Black, while 10.4% of Worldwide Campus graduate enrollment was Black.

“Gen. Brown makes us proud that we have been part of his ascension to this level,” says Watret. “We at Embry-Riddle are looking to increase our diversity and inclusion and … look at underrepresented minority groups in terms of support [services] because the aviation industry is a good career to get into and there is going to be a demand for professionals.”

In addition to his bachelor’s and master’s degree programs, Brown took part in Air Force training, including being a distinguished graduate of Air Command and Staff College and a National Defense Fellow.

“As the technical requirements … of warfare weapons systems and human dynamics … get more and more complex, education becomes more central to your ability to handle those complex things,” says Cheek. “Education is a continuous process.”

The career path

Prior to becoming Air Force chief of staff on Aug. 6, Brown was commander of Pacific Air Forces, air component commander for U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and executive director of the Pacific Air Combat Operations Staff. This put him in a position overseeing more than 46,000 airmen. Brown is not the first Black four-star general; but of the more than 40 current senior commanders in the military, only two are Black.

In his video, Brown, who was not available for an interview due to preparation for his new role as chief of staff, said, “I’m thinking about my historic nomination to be the first African American to serve as the Air Force chief of staff. I’m thinking about the African Americans who went before me to make this opportunity possible.

Vacchi says it is inappropriate to put pressure on “firsts” to create change in some legendary way. Despite Brown’s historic appointment, Vacchi doesn’t see that as likely impacting the number of young people of color pursuing leadership positions in the military because those who ascend to senior leadership positions in all branches of the military are people who have served in combat positions.

Brown is a fighter pilot, “the epitome of who it is that does the fighting in the Air Force,” says Vacchi, who saw a reticence among Black students and their families to pursue combat roles when he oversaw the ROTC program at University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Cheek says it has been a challenge for the Air Force to recruit people of color as pilots, especially in combat roles.

“In the Army, it’s been a challenge to get African American males to join the infantry, which is where the leaders of the Army come from,” he says. “I sure hope [Brown] inspires more individuals of color to join the Air Force and to become fighter pilots and other pilots that are going to be the nucleus of leadership of the future of the Air Force.”

The next generation

“That [Gen. Brown] is a gifted and inspirational leader will no doubt positively affect both recruiting and retaining young men and women of color in our military,” says Cheek.

Vacchi sees Brown’s greatest potential for influence in showing young men and women of color the positive difference that higher education can make. Brown would not have achieved his military success without degrees.

“I think Gen. Brown would embrace that effect-goal on society vigorously,” says Vacchi, who addresses issues of access to higher education in his work. “If his ascension to this position serves to inspire Black youth and/or any youth to seek a college degree, this will be an important legacy, perhaps more important than anything he might accomplish as Air Force chief of staff.”

Most people in the military are enlisted personnel, some of whom may want to become officers. To do so requires higher education. Vacchi would like to see more opportunities for enlisted personnel to pursue college, noting that the Air Force led the way with its well-organized Community College of the Air Force, which allows service personnel to earn college credit for military service and training and enables them to earn associate degrees.

“If Gen. Brown encourages his airmen and women to use their active duty college benefits and then to use their GI Bill benefits when they separate, he’s doing everything he can and should do as a senior leader to advance his members and future veterans to be all they can be academically,” says Vacchi.

This article originally appeared in the September 3, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.