For infectious diseases doctor Siham Mahgoub, some diligent “detective work” and plenty of curiosity are what many medical breakthroughs in challenging patient cases are made of. Now that she is on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic, Mahgoub admits that the stakes are higher and the learning curve is steep, but her approach remains the same.

On any given day, in their battle with a virus they can’t see, but can infect or kill them, Mahgoub wants her medical residents to remember this: don’t be afraid. In a pandemic, she said, “Fear is your worst enemy. And being anxious can make you forget something,” such as any aspect of personal protective equipment that they must wear like armor against a possible fatal contagion.

No room for error, no room for fear

The focus may be on COVID-19 and keeping patients alive, but Mahgoub still has non-COVID-19 patients to see. Some have HIV, another virus without a cure, which she has spent years studying and treating. But the constant buzz of the second pager she now wears signals the shifting demand in her caseload at HUH — and the new day that the coronavirus has ushered in. Mahgoub is needed for a consult.

“When my COVID-19 pager goes off, I have to respond to questions from the medical team about a suspected case. They’re usually wondering if a patient can safely stay at home” or needs to be come to an emergency room where risk of infection can be high and the medical team stretched.

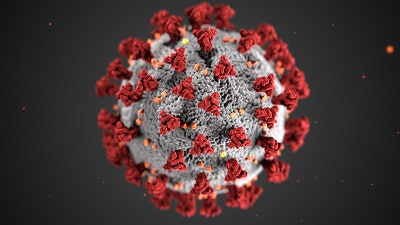

Navigating through an unknown maze touched off by SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19, has made Mahgoub an even more voracious reader of journal news from her field. Now, between hospital rounds and consultations, she is downloading and devouring the latest safety and treatment guidelines and literature on the science and research that’s quickly being cranked out almost as rapidly as the virus is spreading. One of her roles on the hospital’s COVID-19 Task Force has been to summarize all the information and share it with others on the team.

“We’re dealing with a pandemic and there is no room for error or the chance to miss something,” says Mahgoub, who needed to also build regular, national calls with fellow infectious disease trackers on COVID-19’s trail, into her packed days.

Keeping patients alive

In late March, out of desperation and with little data, Mahgoub and HUH, decided to administer hydroxychloroquine, a now controversial but decades old drug, to patients hospitalized with a new virus.

“We couldn’t just look at them and see them die,” says Mahgoub, who spearheaded a new HUH taskforce made up of colleagues from the clinical pharmacy, critical care and infectious diseases departments. Their aim, she said, to devise a drug protocol for those sickest with COVID-19. Today, without a proven antiviral or drug to treat COVID-19, the most that healthcare workers can provide their patients is oxygen, supportive care, and if needed, a ventilator to help them breathe.

Although she said HUH cannot conduct “a clinical trial,” selected COVID-19 patients are receiving hydroxychloroquine, a drug approved to treat malaria and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

“In the meantime, she added, “we are as desperate as other institutions around the country that do not have access to a clinical trial. We had to offer our patients treatment, even with the limited data we have.”

Despite slim evidence on its efficacy, the Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, which allowed hydroxychloroquine to be used to care for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who cannot be part of a clinical trial. While President Trump has championed the drug, calling it a “game changer,” many medical and scientific experts warn of its negative and serious health impacts.

‘Prevent, prepare, respond’

As care for COVID-19 patients at HUH advances, “we will update our guidelines” for the drug therapy, Mahgoub says.

Knowing how those patients eventually respond to the drug will be pivotal in the next few months as the hospital ramps up for a potential summer surge in COVID-19 cases in the Washington, D.C. region. The historically Black Howard University, a federally chartered institution, operates HUH, now designated as one of the District’s COVID-19 treatment facilities. In the $2 trillion federal relief bill passed in March, Howard was allocated $13 million to “prevent, prepare for and respond to coronavirus.” Gallaudet University, another federally chartered institution in the nation’s capital, received $7 million in the relief bill.

Recently, Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser set a specific mandate for all District of Columbia Hospital Association members in response to the city’s comprehensive COVID-19 medical surge plan. It calls for boosting available hospital beds, intensive care unit capacity and ventilator availability for COVID-19 patients. The directive also called for every D.C. hospital to increase bed capacity by 125% within its existing infrastructure. To meet the directive, HUH is expanding its bed capacity, says Dr. Hugh E. Mighty, Howard University’s vice president of clinical affairs and dean of the College of Medicine.

He said those plans include transforming several wings of the facility to care for patients with COVID-19. One such space is its 6-West Wing, which was previously used for teaching in the university’s College of Nursing. Soon, hospital staff will use it to separate patients who have coronavirus symptoms from other patients to reduce the chances of spreading the infection.

“We are fortunate to have spaces in our facility and are able to reconfigure and relocate some of our existing units to make surge space for the additional beds,” said HUH CEO Anita L.A. Jenkins, the hospital’s new CEO. “We are now in the execution phase to achieve these goals. HUH will be ready to serve our patients during these extraordinary times.”

Perhaps the most visible sign that this pandemic could soon cause an outsized need for urgent patient care is the new triage tent that has been erected on the grounds of the main HUH. The triage tent, Mighty says, will expand the capabilities of the hospital’s emergency room. The space will be equipped with independent bays where medical staff can triage, or evaluate, patient symptoms and provide treatment inside the main hospital. It’s set up will also allow hospital staff and patients to maintain proper social distancing during the treatment process.

Jenkins says HUH could expect at least 5,000 in-patient admissions during the course of the outbreak, but “Howard University Hospital is ready to be a part of the solution to help the DMV [D.C., Maryland and Virginia] get through these trying times.”

This article originally appeared in the April 30, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.