Dr. Mareena Robinson Snowden, the first Black woman to graduate with a Ph.D. in nuclear engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), describes having an adversarial relationship with math and science as a child, fearing her classes far more than enjoying them.

“Every time I got a question wrong or a teacher called on me and I didn’t know what he was talking about, it further confirmed to me that this wasn’t for me, that this wasn’t the field I should pursue,” Robinson Snowden said.

What she would realize later, however, is that her struggle was a normal aspect of learning nearly everyone faces, saying, “We often give students

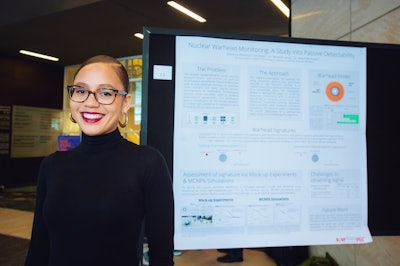

Dr. Mareena Robinson Snowden

Dr. Mareena Robinson Snowdenthe lesson before we teach them how to learn.”

“It can be pretty demoralizing, this idea that you’re going to get the answer wrong a bunch of times before you get it right,” Robinson Snowden added. “But it’s not because you’re not good at the subject, it’s just because struggle is required to learn anything.”

For women and underrepresented minorities in STEM, internalizing that struggle as evidence of “science is not for me” may be harder to escape. For that reason, Robinson Snowden has been a steady advocate for women, especially women of color, entering STEM.

In fact, BET Network’s Black Girls Rock! awarded her with the Girls Rock Tech Award in 2018 for her work and advocacy.

During her acceptance speech, Robinson Snowden spoke directly “to any young girl who may be watching, who has even the smallest inclination toward science or engineering,” saying, “the truth is that you are a legitimate participant in that space and we need you.”

It was an impassioned speech for someone who calls herself “very practical, very matter-of-fact.” After all, she says the decision to enter STEM itself was more out of necessity than passion.

From a single parent home, Robinson Snowden chose to study physics, because she knew opportunities would be available upon graduation, opportunities that would, as she put it, “pay the bills.”

“For me, college was a very practical exercise,” Robinson Snowden said. “I knew physics was going to be hard, but if I could master it, I would have options. A lot of my choices, as I look back on them, have been trying to maximize my options. Trying to get as many choices as I can, as many doors open as I can. And physics, really any fundamental science or math, is exactly that.”

Not only would there be options available, but there would be help, she added, referencing the large amount of scholarships, grants and fellowships devoted to increasing the STEM pipeline.

Robinson Snowden obtained a bachelor’s degree in physics from Florida A&M University (FAMU), where she relished the experience of having predominantly Black professors and classmates.

“There’s something intoxicating and captivating and deeply influencing about being in that space,” Robinson Snowden said. “Those are really crucial years in the formation of yourself, and the sense of self that I established there has definitely helped guide me.”

After building a foundation at FAMU, Robinson Snowden then went on to MIT which was, to say the least, quite different from the HBCU turf she had just left.

Dr. Mareena Robinson Snowden

Dr. Mareena Robinson Snowden“To say culture shock is an understatement,” Robinson Snowden said. “The courses at that point were predominantly male and predominantly White. And when I say predominantly, I mean I’m the only female in the room or maybe there is one other.”

However, for any one negative interaction at MIT, she said there were “ten positive and affirming interactions.”

That’s in part thanks to MIT’s Summer Research Program (MSRP), which Robinson Snowden participated in as an undergrad, allowing her to grow comfortable with the campus and build a network of support. Founded in 1986, MSRP provides nine-week summer internships, research projects and free housing to talented and underrepresented students pursuing STEM.

After six years at MIT, Robinson Snowden successfully defended her Ph.D. thesis in 2017 and she hasn’t slowed down since. Upon graduating, she participated in two year-long fellowships at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where she was able to brainstorm solutions to nuclear security problems regarding Iran and North Korea, and the National Nuclear Security Administration, where she was responsible for stewarding the nuclear stockpile itself.

What’s more, as if performing critical research on nuclear arms control wasn’t challenging enough, Robinson Snowden also gave birth to her first child.

“I knew that I wanted to have a very exciting and rewarding professional life and I also wanted to have a very exciting and rewarding personal life. It’s not an easy juggle, but you do what you got to do,” she said, again emphasizing her matter-of-fact approach to life.

Robinson Snowden is now a senior engineer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory where she studies some of the toughest security questions facing the nation and the world: Who should and who shouldn’t have nuclear weapons? How and when should they be used? And how do you convince a nation such as North Korea to give up their nuclear programs?

Whereas some questions in STEM hold objective answers that remain the same regardless of who’s doing the math, Robinson Snowden said it’s the messier and abstract questions that reveal just how pertinent diversity is in STEM and, in turn, national security.

“Those types of intersectional questions make it obvious why we would want to have a diverse group of people,” said Robinson Snowden. “If you have people with the same viewpoint of the world, they will have a very limited set of solutions that they can provide to any one problem. … So, if you want to get the most thoughtful, widest range of solutions to any one type of problem, you have to make sure that the people who are contributing represent the wide span of our lived experiences.”

This article originally appeared in the May 14, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.